- Russian tourism and crime seem to go hand in hand at exotic locations where they holiday to escape the cold. In Bali, they’ve just about had enough

The alleyway is like thousands of others in Bali, power lines dangling, yellow-white frangipani flowers creeping along the brickwork, but here, a wanted poster is stuck to the wall, and not one of local suspects but of a couple of Caucasians.

The first mugshot is of a man in his 30s with a thin patch of blond hair. The second is of a woman of about the same age with a sharp brown bob. “Immigration of Ngurah Rai. Most Wanted,” the poster declares. “Andrei Kovalenka Alias Andrew Ayer and Ekaterina Trubkina. Russian nationals.”

Kovalenka had just completed an 18-month sentence at Bali’s notorious Kerobokan Prison for possession of more than half a kilogram of hashish, and had been moved to an immigration detention centre, pending deportation to Russia over an arrest warrant for unspecified charges shared on Interpol’s red notice list when Trubkina managed to track him down and somehow bust him out.

The couple spent two weeks on the lam in February before they were discovered at a villa, just around the corner from this alleyway adorned with their mugshots, on the fringe of Bali’s surf and nightlife hub of Canggu. In March, Trubkina was deported and Kovalenka was extradited.

Indonesia’s borders have been closed since April 1, 2020, and yet hundreds of thousands of tourists have found shelter in Canggu during the pandemic, many by paying Balinese immigration agents to get them into the country on social visas – a legal loophole closed in July, when Indonesia briefly became the global epicentre of the pandemic, but that has now opened again.

These tourists came from the Americas, Europe and parts of Africa, but the largest country of origin, accounting for 67,491 arrivals in 2020, according to Statistics Indonesia, was Russia.

He used to install spy cameras in China, now he roots them out

It is not difficult to understand why so many young Russians, particularly those working online or in creative industries, wanted out. Take the Russian government’s use, and abuse, of Covid-19 tracking apps. When someone tests positive in Moscow, they have to download an app that constantly monitors their geolocation.

If the app detects a position more than 50 metres from their home, they are fined. But according to the Moscow-based Memorial Human Rights Centre, people have been receiving fines equivalent to tens of thousands of dollars because the app’s GPS is not always accurate.

The Russian government’s official narrative is that the country has handled this pandemic better than most and is on the road to recovery, but nothing could be further from the truth. Russia has one of the highest Covid-19 fatality rates in the world.

Official figures published by its statistics agency Rosstat show that the country’s excess deaths have topped 660,000 since the start of the pandemic. Indonesia, in comparison, has recorded more than 143,000 deaths, of which 3,000 have been in Bali.

Mathematical analysis by the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation points to the Southeast Asian nation’s real fatality rate likely being twice that number, but still nowhere near as bad as in Russia, which has half the population of Indonesia.

Still, with little in the way of social security and more than 100,000 unemployed, the roubles and euros spent on the island over the past 18 months have meant that thousands of Balinese children have not gone to bed hungry.

“There’s a Russian guy in my guest house who orders pizza every night for dinner,” says an Indonesian woman living in a cheap guest house in Canggu, where every room other than her own is occupied by Russians or Ukrainians. “He knows my daughter loves pizza and that I can’t afford it, so he always brings her a slice.”

But anecdotes about the warmth and hospitality of Russians are minority reports in Bali, where they are increasingly running afoul of the law. Of the 157 foreigners deported last year, more than half held Russian citizenship, including a woman who left her hotel and was caught strolling around outdoors after testing positive for Covid-19.

Russian influencer Sergey Kosenko became the most hated man in Bali in December 2020, after riding a perfectly good motorbike off a pier into the ocean, a bikini-clad Russian model in tow, all for a stylised social media clip. After apologising for being insensitive to the hardships faced by locals during the pandemic – as well as the fact he was working illegally in Indonesia – Kosenko threw a huge party at his villa. Only then was he deported.

The list goes on. In May this year, Russian model Leia Se joined Bali’s personae non gratae after painting a mask on her face to trick a security guard into letting her into a supermarket for a YouTube stunt. In June, police launched an investigation after pornographic video clips shot at a villa in Canggu with Russian music playing in the background went viral on social media (pornography is illegal in Muslim-majority Indonesia).

Only two of a dozen-odd suspects who starred in the film were identified – a pair of Germans who left the island before police could catch up with them – but Russian activity in Bali’s flesh trade is well documented.

There are scores of ads for high-class Russian sex workers on websites such as escort-bali.com and Locanto, and Russian sex workers populate Tinder. The island is also a bolt-hole for Russian porn stars such as Veronika Troshina, a 22-year-old who became public enemy No 1 after a video posted on Pornhub.com last year showed her having sex on Mount Batur, a holy place for Balinese Hindus.

In July, Russian-linked crime in Bali took a disturbing turn when police arrested a Russian national identified only by his initials, EB, who allegedly visited a Ukrainian man’s motorbike rental business in Canggu, accused him of operating illegally and forced him to hand over US$27,661 worth of cash and motorbikes while claiming to be an Interpol agent.

To ensure the Ukrainian’s silence, the Russian also threatened to falsely report him to police for being a drug dealer.

“We have only arrested one [such perpetrator, but he] must be part of a group,” the head of Bali Police’s General Crimes Unit, Djuhandhani Rahardjo, said at the time. “We are sure that there are other victims who may be afraid to report to police.”

Yuliya Zabyelina, associate professor of international criminal justice at the City University of New York, agrees, saying “because Bali is not well governed, there is a security gap. Tourists don’t have faith in the police, so extortion rackets like this begin taking place.”

The high incidence of misbehaviour among Russians and Russian-linked crime has seen both locals and tourists become resentful. In 2019, news website Kumparan.com quoted Bali Tourism Board chairman Ida Bagus Agung Partha Adnyana as saying that “Russians love to make trouble. That’s their behaviour. Maybe we need tighter control over these Russians?”

Victor Kriventsov, deputy honorary consul of the Russian Federation in Pattaya, Thailand, says Russian tourists are fundamentally different to those from most other countries. Kriventsov’s adopted home of Thailand is all too familiar with Bali’s current problems with Russian tourists who “try to create a Russian environment wherever they live”.

“They don’t see a real benefit in learning other languages,” he says, “and as Russians have only been travelling abroad for the past 20 years they are not really comfortable.”

Pattaya, located some 150km southeast of Bangkok, boomed as an R&R (rest and recuperation) destination for American troops during the Vietnam war, where all the activities that might be expected of soldiers at play flourished, setting the tone for the town.

By the 1980s Pattaya had become the sex and sleaze capital of the world. In 1992, a year after the fall of the Soviet Union, flights from Moscow skipped Bangkok altogether and landed at U-Tapao Airport, a former US Air Force base south of Pattaya.

Russians came in the millions to soak up the sun and tens of thousands more made the city their home. They invested in Russian restaurants, Russian condos, Russian grocery shops and Russian clubs with names, such as Crazy Russian Girls, that leave little to the imagination. The Russian mafia followed.

“Russian-organised crime circles established a presence in Thailand in the 1990s after the collapse of the Soviet Union,” reads a declassified US diplomatic cable from 2009. “There is now a large presence of Russian organised crime networks around the popular beach destinations of Pattaya.”

In “The Economic and Social Impact of Transnational Crime in Pattaya City”, a 2012 study by Thailand’s Burapha University, Russians were identified as the nationality most involved with crime in the city: “Money laundering, drug dealing, investment in real estate, financial and securities fraud, human trafficking, murder, cybercrime, and smuggling of stolen vehicles. Thai people have not thought about the dangers of transnational crime from Russia.”

Reports on Russian-linked crime in Pattaya have been appearing in publications such as the Bangkok Post and Pattaya Mail for decades. Sometimes Russians have been the victims – robbed, raped or murdered, such as when, in 2015, a 39-year-old man was beaten to death in the hallway of a hotel.

These Russians have all kinds of vices and the moment Russian tourists come to one place all other tourists flee from thereLaxmikant Parsekar, former Goa health minister, as quoted in reports

On other occasions they have been the bad guys, not least in 2017, when Pattaya police rounded up 14 mostly Russian crime suspects during a month-long blitz. Matvey Shuvalov, accused of defrauding Russian investors of US$250,000, had been hiding in Thailand under a false identity for more than 20 years and had built close relationships with high-ranking city officials.

“These people have formed criminal gangs, stolen jobs from locals – at restaurants, entertainment venues, car rental businesses and other places,” Police Lieutenant General Nathathorn Prousoontorn told the Bangkok Post at the time, “not to mention operated illegal businesses in the tourism sector involved in the sex and drug trades.”

Reports of Russian-linked crime in Pattaya have slowed during the pandemic because of Thailand’s border closure but the Russian mob has been working on that, too. In March, police raided a house in Pattaya where Russians Irina Prokasheva and Alexey Luptov were running a website that provided fraudulent statements from a bank in Russia for clients seeking resident visas in Thailand.

A few weeks later, Garanin Konstantin, a Russian who had been living in Pattaya for six years, was arrested for selling crystal meth to sex workers, often receiving sexual favours as payment.

In the ’90s the demographic changed, with young Israelis decompressing after compulsory military service dominating the party scene. By 2010, the tables had turned again and Russians surpassed Israelis as the largest group of visitors in Goa, with half a million arrivals a year.

“We welcome all international tourists including the Russians, whoever is going to boost our economy,” Michael Lobo, a member of the Goa Legislative Assembly for Calangute, told Russian media in 2014. “But there are some Russians who are doing illegal business here.”

Goa’s then health minister Laxmikant Parsekar was quoted as saying: “These Russians have all kinds of vices and the moment Russian tourists come to one place all other tourists flee from there.”

In the 3½ years to August 2014, police in Goa registered 182 narcotics cases against Russian nationals.

“Who runs Goa then?” asked a Times of India piece in 2012. “Ask the average man on the street and they will tell you with a knowing smile – the mafia. First it was the Israeli mafia and now it is the all-powerful Russian mafia. Nobody wants to take a chance with them. The political class love it because they don’t have to make too much of an effort to make their bucks. All they have to do is support the mafias.”

A report in the same year by The Economic Times stated: “In Goa, the Russian mafia is everywhere. You are knowledgeably told about land grabbing and crime syndicates and drug and prostitution rings operated by Russians.”

Mystery of Jewish gangster who spied for the Japanese in Shanghai

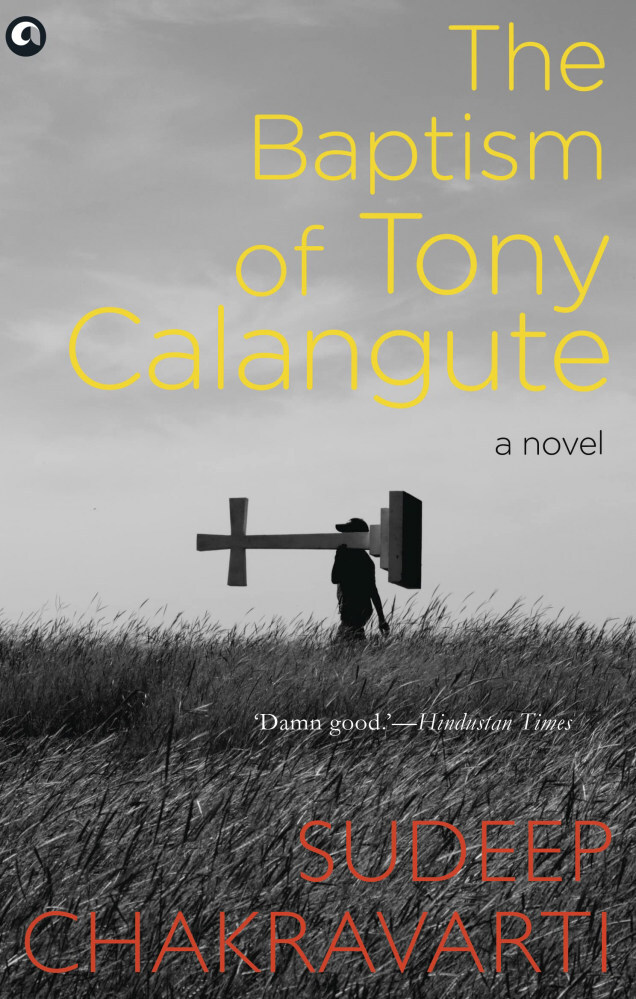

Sudeep Chakravarti – an Indian author whose 2018 novel The Baptism of Tony Calangute features a brutal Russian drug lord called Sergei Yurlov – believes Russian organised crime in India mirrors leisure rackets initiated by the Japanese Yakuza in Hawaii in the ’50s.

“The Japanese underworld followed this major destination of Japanese leisure travellers with investments in hotels and condominiums. Yakuza-controlled travel houses, sex and entertainment drugs became a corollary. Altogether, it was also a convenient way to launder off-system cash and build legit business fronts,” the author wrote.

“A similar template has now arrived in Goa with the Russians, who have plugged into and expanded the already robust drugs and sex circuits in Goa that cater to partygoers from several nations, and several states of India.”

The Russian mob also control scores of brothels in Goa, where sex workers are “in every sense slaves to their masters, who subject them to brutal beatings if they dare to protest on any pretext”, the Goa Chronicle reported in April. “A complaint from a customer about a girl being uncooperative can result in severe whipping with a steel-studded leather belt.”

Goa and Pattaya are not the only destinations affected by the Russian leisure racket. On the Costa del Sol, Spain’s tourist magnet, Russian nationals have created thousands of shell companies as fronts for money laundering used to finance drug- and human-trafficking operations, according to the country’s National Police.

The Russian mob has also established a significant presence in Dubai, according to a 2019 dossier compiled by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. But as of now, no data or statements from law enforcement agencies exist to suggest this has been replicated in Bali, and some experts say the recent surge in Russian-linked crime on the island may simply be an unwanted side effect of the pandemic.

Whether the phenomenon will continue post-pandemic remains to be seen. But as headlines show, they’re off to a bad start.

All you need for this kind of crime to flourish is a police force that is unresponsive to tourists and incapable or unwilling to provide them with securityYuliya Zabyelina, associate professor of international criminal justice, City University of New York

Some politicians in Bali have suggested banning Russians from obtaining visas on arrival when international tourism resumes. But this will not prevent criminal transplantation from Russia, says Zabyelina of the City University of New York: “There is always a way to get a visa with fraudulent documents or get into the country illegally.”

Her suggestion is as simple as providing ways for Russian tourists to communicate with police, immigration and other government agencies.

“I would recommend a 24/7 hotline with Russian-speaking workers so that there is a clear way for tourists and Russian-speaking business owners to communicate with the authorities to report crimes like extortion,” she says. “They need to know the police will take their information seriously and deal with it with care.

“It would be helpful if the Russian-speaking communities in Bali raise awareness among Russian tourists about some possible risks that may await them. That’s what’s missing now and this is how Bali can start its response to the growing threat of Russian organised crime in Indonesia.”

Among us: the secretive, subversive history of spying in Hong Kong

Bali provincial police, the tourist police, the Bali Tourism Board, the Ministry of Law and Human Rights, the director general of immigration, the director general of corrections, Kerobokan Prison and every single government agency contacted refused to comment on Russian-linked crime on the island.

The deafening silence is a product of various interweaving factors: Covid-19 health protocols that mandate low staff numbers at government offices; the fact that Indonesians prefer to avoid conflict and discussing unpleasant topics in public; and that, as with Goa and Pattaya, Bali is a hotbed of corruption. Transparency International’s global Corruption Perception Index ranks Indonesia 102 in a list of 180 countries. Thailand is ranked 104, and India 86.

Graft is well-documented in criminal proceedings in Indonesia and before the pandemic, many policemen in Bali spent their days pulling over tourists for non-existent or minor traffic infractions, then demanding hundreds of dollars to look the other way.

Until recently, one could pay a US$600 bribe at Jakarta International Airport to avoid mandatory quarantine. Everyone from the airlines, to immigration, to airport security and visa agents were in on the scam.

Then there is the Italian mob, which can get you a long-term visa and work permit in Bali – documents that take months to secure through official channels – in a matter of hours.

Zabyelina says she does not think Russian organised crime poses an “urgent threat” to Bali but warns that studies of the Russian leisure racket, with Goa and Pattaya being textbook examples, suggest a decade from now things could be very different.

Zabyelina believes the Russian who posed as an Interpol agent in Bali and his co-conspirators were likely “small-time criminals trying to make a living” in order to avoid returning home and to instead spend their days relaxing on the beach. She also believes the pandemic “may have something to do with” the criminal uptick, since many foreigners are stuck in Bali with no money to return home, or do not wish to leave because of lockdowns in their home countries.

“Setting tourists up with drugs in a country like Indonesia, with tough penalties for offences including the death sentence, is another common extortion scam,” says Zabyelina. “It’s how criminal organisations get started in foreign locations as it doesn’t require capital or any particular skill.

“And if it’s not tackled at the very start the groups may be able to settle down in Bali more permanently and even transition to more sophisticated and profitable criminal enterprises like drug trafficking, human trafficking and wildlife trafficking,” she adds, referring to a 2019 incident in which Russian Andrei Zhestkov was stopped at Bali’s airport with a drugged baby orangutan in his suitcase. Zhestkov claimed he had bought it off another Russian for US$3,000.

“There is no evidence to suggest which comes first – Russian tourism or organised crime. I think they go hand in hand at exotic places where Russians like to go on holidays to escape a cold climate,” Zabyelina says.

“All you need for this kind of crime to flourish is a police force that is unresponsive to tourists and incapable or unwilling to provide them with security.”