- Spies have been part of Hong Kong since the earliest days of British rule. Some were caught, others fled, but for a few suspects we might never learn the truth

On June 8, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor warned the city’s universities not to let their students be “easily indoctrinated” after being “penetrated by foreign forces” bent on “brainwashing”; forces who either “want to undermine the Chinese government, or have ideological prejudices against China”, expressing that she had “no doubt” that “ulterior motives” were at play, confirming her belief that “these external forces are at work”.

Which external forces were these exactly? She declined to say.

As far back as the beginning of Hong Kong’s tenure as a British colony, in 1841, there has been an element of clandestine intrigue about the place, imagined or otherwise. In Hong Kong, spooks have always been among us.

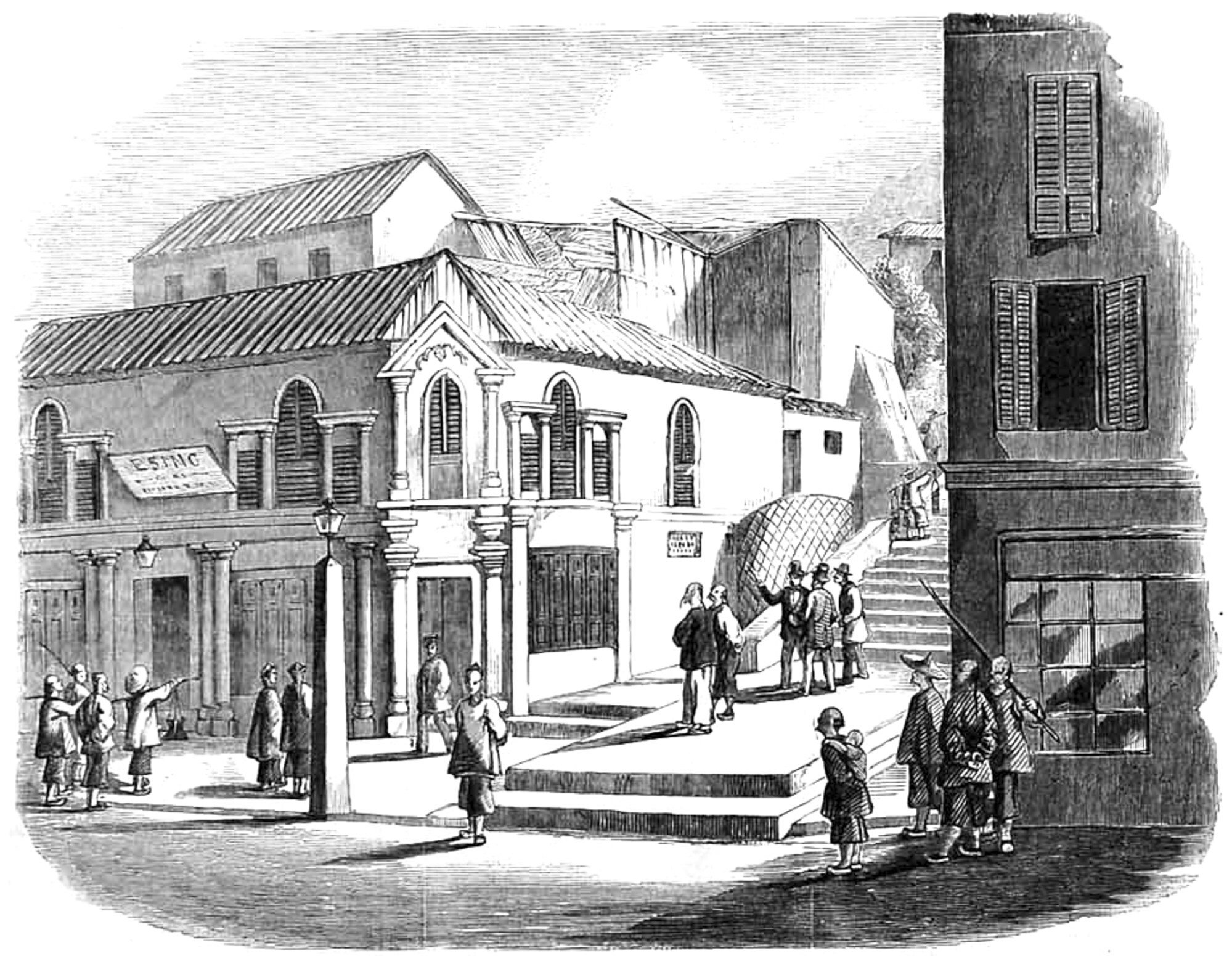

In 1857, with the second opium war under way between Britain and China, the emerging city was plunged into its first spy panic. But when it came to identifying the source of the subversion, the culprit did not appear to be a highly trained military infiltrator or a suave secret agent. That January, when several hundred Europeans – including soldiers at the British garrison – were poisoned by arsenic in bread baked by a Chinese-owned store, the spirit of that time led many to conclude that the Esing Bakery was a front for mainland infiltrators.

Once the nausea and vomiting subsided, the bakery’s owner, Cheong Ah-lum, appeared in the dock – apparently a bemused local businessman unable to account for the tragedy. But others believed Cheong to be a master spy, and his shopfront a sly ruse.

By August of that year, the war was not going well for Britain. As far afield as the American capital, The Washington Union newspaper reported that there was an “Extirpation Association’’ dedicated to undermining British control of Hong Kong and returning it to Chinese rule. The association’s “sleeper” spies were said to be numerous in the colony, rumour-mongering that the British were close to defeat, that food supplies were running low and mass starvation beckoned; these subversive elements were thought responsible for the Esing Bakery poisoning, and could do it again.

China-backed power plant in Myanmar casts a long shadow

Two British historians who have studied the poisoning scandal, Kate Lowe and Eugene McLaughlin, concluded that although the truth of the incident has never been conclusively uncovered, it was clear, at the time, that the British believed “the poisoning was simultaneously an act of mass terrorism, a war crime and a criminal conspiracy and they held Cheong Ah-lum responsible for it”.

Ultimately Cheong was acquitted at trial due to lack of evidence, but that did not stop him being banished from Hong Kong and leaving for Macau.

It will likely never be known if the Esing Bakery poisoning was the work of Qing-dynasty spies looking to undermine British rule in Hong Kong, or just a bad batch of dough. What the Esing Bakery incident did establish was the ease with which political objectives could be advanced by pant-hooting about conspirators and secret plots. This is not unique to Hong Kong, but it has been a tradition in the city that has stuck around.

Nearly 40 years later, in May 1896, suspicions were cast on a group of Germans on Stonecutters Island (Ngong Shuen Chau, now part of Kowloon following land reclamation).

Albert Harrasowitz, captain of the Hohenzollern, a German mail steamer calling at Hong Kong, and his shipmate Max Rudolph, who claimed to be the vessel’s doctor, were arrested on Stonecutters Island carrying what the newspapers called a “detective’s hand camera” and supposedly taking pictures of the island’s fortifications. The men said they were just there for a ramble, to snap some photos of the local flora and fauna. A court, however, disagreed, and sentenced both men to three months in prison.

It was not so much that the evidence was solid but that it was a bad time to be a wayward German in a British colony, one that was quickly assuming suspicion as a social characteristic.

Relations between London and Berlin had become acrimonious over Germany’s nascent imperial expansion and incursions in southwest Africa, soon to boil over as the kaiser sent troops to counter the British in the Boer war.

The media barbs were largely fuelled by the Daily Mail-owning press baron Lord Northcliffe, who had a distinctly anti-German agenda. Whether Harrasowitz and Rudolph were really spying on Britain’s defences was not clear, but colonial authorities deported them both anyway.

Naturalists or enemy agents, the Stonecutters case did show that Hong Kong had become a key location for global geopolitical manoeuvring. Harrasowitz and Rudolph might have been innocent but there was also no doubt Germany was envious of Britain’s imperial power and sought an understanding of its naval and military capabilities, both in Hong Kong and across Asia.

And even if not involved in a conflict directly, its key location meant the Fragrant Harbour was often awaft with subterfuge. In 1898, as faraway Spain entered a war with the faraway United States, “foreign influences”, “rumour-mongers” and “destabilising forces” got to work as far away from the action as Hong Kong.

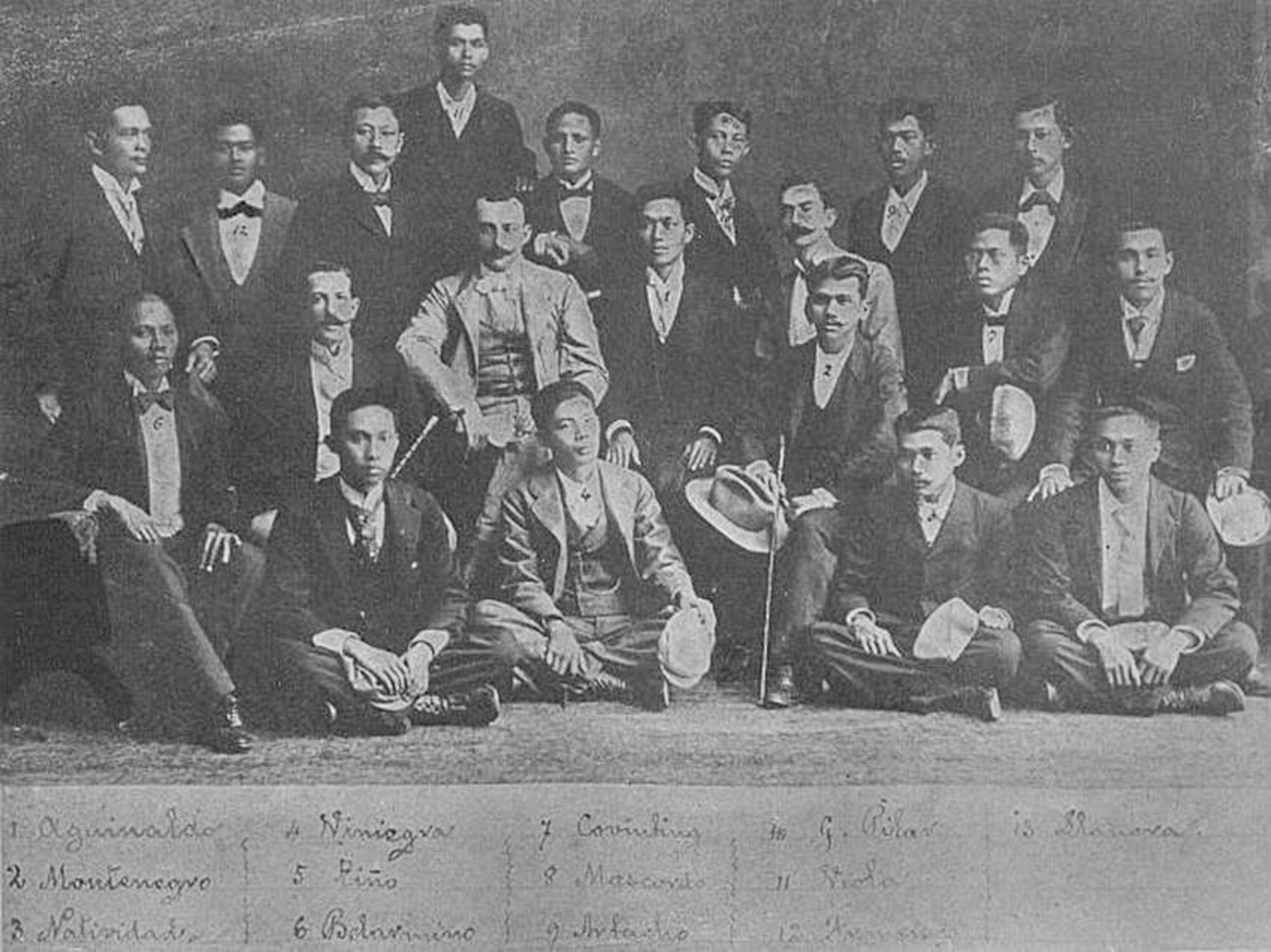

Armed conflict had broken out in the New World in 1898, starting in the Caribbean, and after 10 weeks of war the US had triumphed. Along the way, the US Navy’s Asiatic Squadron, stationed in Hong Kong, sank a Spanish squadron in Manila Bay and thus also took Spain’s Pacific territory of the Philippines. With some alarm, Hong Kong watched the fighting drift its way, from the Caribbean to the Pacific. And that was when Spain’s agents in Hong Kong were ordered to begin their own disinformation campaign.

Rumours began circulating that the US Navy was being roundly defeated in the waters off Cuba, that Admiral George Dewey, who had led the attack on Manila Bay, had been assassinated and that the Filipino revolutionary Emilio Aguinaldo had gone over to the Spanish side. All lies, of course: Aguinaldo was aboard the USS McCulloch under Dewey’s command and being taken back to the Philippines from Hong Kong, whereupon he resumed command of revolutionary forces. The Spanish spies melted away. Or perhaps they never existed. Maybe it was just tavern gossip.

A few years later, when war broke out in Europe, another kind of foreign influence campaign came to Hong Kong, in which aside from suspicions of infiltration, allegiances and loyalties would be tested, and as Hong Kong has always demanded, sides would have to be chosen.

With the outbreak of World War I, in 1914, Hong Kong was only briefly troubled about Germany. The kaiser’s naval forces in Asia were easily contained by Britain’s ally Japan, and there were enough British ships to defend the port. Mainland China offered some cause for concern, but the nascent republican government was deeply divided and then, in 1917, China officially became an ally. More worrisome to the authorities were the loyalties of the many Indians in the colony, including those serving in the police, as watchmen, as well as one Indian infantry battalion.

The authorities came to hear of “very strong anti-British feeling” among the Indian community, an echo of various anti-colonial and pro-independence movements back in India. This fervour was thought by British authorities in Hong Kong to have been stirred up and financed by the Germans, aiming to foment unrest and trigger a pan-Indian mutiny in the British army’s Indian regiments, from Punjab to Singapore, and as far east as Hong Kong.

Colonial leaders took these threats seriously – the thwarted Ghadar Mutiny, said to have been planned to take place in 1915, led to Punjab CID sending teams to Hong Kong to try and root out any potential leaders. Ultimately Hong Kong remained calm, though in Singapore a week-long mutiny by Indian troops did occur, and ended in bloodshed.

It was believed pirates had spies in all the Hong Kong banks, the biggest Hongs, in the Customs department and all along the wharves

The British Empire survived the first world war, and British Hong Kong survived the Ghadar Mutiny, though it would not be so lucky the next time around.

On September 3, 1939, Britain and Germany went to war once again, and within minutes of the announcement, male German citizens in Hong Kong were rounded up and interned at La Salle College. There was never much evidence of Nazi spies in Hong Kong, despite their proliferation in Shanghai and Tokyo. Reportedly a couple of German internees at La Salle told the newspapers they would rather get two square meals a day in Hong Kong than return to the Fatherland.

After a month or so, many Germans deemed not to be Nazis were released and reunited with their families. Most took steamers to Shanghai. The rest were gone within a few months after prisoner swaps.

But it was the Japanese the British should have been worried about. In two 1942 films, Secret Agent of Japan (Hollywood’s first wartime spy movie after the Pearl Harbour disaster) and Escape from Hong Kong, it is Japanese spies who threaten the colony. And this fiction is not far removed from fact.

Through a covert organisation known as the Koa Agency, China expert Lieutenant Colonel Yoshimasa Okada had been tasked with giving all possible support to the Imperial Japanese Army through deception, espionage and information gathering. Expert in Japanese wartime intelligence Ken Kotani claims the Japanese used Hong Kong’s triad criminal gangs as intelligence gatherers. Kotani even states that a Chinese-speaking Japanese intelligence officer, Shigemori Sakata, worked within the triads using the code name “Tian”.

By 1948, Hong Kong’s economy was bouncing back after the Japanese defeat while new investment and business was pouring in from the mainland, as entrepreneurs and businesspeople opted to leave before the imminent Nationalist defeat by the Communists. And so, inevitably, serious commercial espionage came to Hong Kong.

American newspapers reported that enterprising spooks, many thought to be former National Army intelligence officers from Shanghai, were forming spy syndicates devoted to buying and selling trade secrets. They even appear to have created a subscription model: for a reported monthly US$8.25 (about US$100 today) local businessmen could obtain information on the nature and quantity of goods being ordered, manufactured and shipped, the main clients, and where they were located around the world.

But the colony’s post-war economic boom was still in its infancy, and while China remained chaotic – old regimes dying, new regimes rising – good intelligence was invaluable, not least to pirates and smugglers who had plagued the waters around Hong Kong, Macau and southern China for centuries.

Even her incredible memory couldn’t save IBM’s Chinese typewriter

By the late 1940s a well-equipped Royal Navy was doing a good job of controlling the area. But the pirates of fabled locations such as Bias Bay (Daya Bay) now reportedly had tommy guns, bazookas and hand grenades, as well as Scotch whisky, expensive Peiping carpets and barrels of shark fins – among the most prized cargoes of the time.

British authorities in Hong Kong and the Chinese Maritime Customs were as impressed as they were frustrated at the formidable intelligence networks the pirates had created after the war. A Royal Navy captain claimed that “somehow or other, they always seem to know which vessels will carry bullion, the most profitable cargoes, and the richest merchants who can be held for ransom”.

It was believed the pirates had spies in all the Hong Kong banks, the biggest Hongs, in the Customs department and all along the wharves. Entering the 1950s, it was reported that Hong Kong authorities believed pirate spies were even penetrating the new airlines flying cargo into and out of the colony.

They were right to be concerned – a flight between Hong Kong and Macau carrying gold bullion was hijacked and disappeared, then another plane flying to Chongqing filled with Nationalist Chinese banknotes vanished, as did a third flying silver dollars to Taiwan.

The final nail in [Little Sai Wan’s] coffin, so some said, was when specially hired deaf-mute cleaners were caught reading highly classified secret documents

The rumour was that hijackers had dumped the crew out of the plane over the sea and taken their haul to a remote location in southern Taiwan. It was impossible to find the planes, which could have landed at any of the more than 50 remote landing strips built by the Japanese during the war. Fighting airborne piracy was difficult enough and Britain had no aircraft devoted to the task, which, of course, the pirates knew thanks to their spies in the Royal Air Force.

Hong Kong survived the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) but the bamboo curtain came down hard and fast. Knowing what was going on “over there” now became a critical mission for Western intelligence.

The early 1950s was a time of true spy mania in the new People’s Republic, and the freshly minted “red” regime became obsessed with the idea of infiltrators, be they American, British, European, Japanese or agents of the defeated Nationalist regime’s pockets of resistance.

The new bosses of China’s intelligence community viewed Hong Kong as one big nest of spies eager to bring them down.

Just how vigilant the new regime was became apparent to three American expats with a penchant for yachting, Donald Dixon, Richard Applegate and Benjamin Krasner, along with the two Chinese crew members they had hired for a day on the waves in 1953. Sailing on Applegate’s yacht, the Kert, they maintained that they never came closer to mainland China’s coast than five miles out, but they were intercepted, arrested and accused of spying on the island of Lap Sap Mei, five miles southwest of Hong Kong.

The situation was compounded by the fact that Dixon and Applegate were journalists and Lap Sap Mei was no longer uninhabited. The Communists had installed a small garrison on the island and large cargo ships from Eastern Bloc countries and non-aligned nations, such as Pakistan, were delivering much needed goods to the PRC, avoiding the narrows towards Whampoa. The Chinese would then transfer the goods on Lap Sap Mei to smaller junks and sail up to Guangzhou. Did Dixon and Applegate know this? What goods Communist China was importing and exporting in return was of obvious interest to any number of intelligence agencies.

In the days before the Kert strayed too close, two British Royal Navy frigates had gone to take a look and been fired on from the island. Hence the alarm, perhaps, when yet another unannounced vessel approached. The Americans and their Chinese crew had to endure rough interrogation and a week held captive on the Kert, followed by house arrest in Guangzhou, where the men remained in detention for 18 months until their release in September 1954.

John le Carré’s Cold War magnum opus is his 1977 novel The Honourable Schoolboy, which flits between George Smiley at MI6 in London and Hong Kong, with a detour to Vientiane, Laos. Jerry Westerby, an “occasional” asset of British intelligence, is dispatched to Hong Kong to (largely) drink at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club bar; the Australian journalist “Old Craw”, who le Carré unabashedly based on the real life “doyen of the Far East foreign press corps” (and also most probably an MI6 asset) Dick Hughes, proves to be a wealth of knowledge.

‘They are all leaving’: is Hong Kong facing an education crisis?

Le Carré always maintained that the Soviets never infiltrated Hong Kong, and that during the Sino-Soviet split (1956-1966), Beijing was content to see Hong Kong run by Britain and encouraged the unequivocal quashing of any KGB actions in the colony, and by default any Soviet spy shenanigans on their doorstep (the paradox being, Beijing and Moscow seemed to hate each other more than either hated the West).

They knew, le Carré believed, that Hong Kong would eventually be returned by Britain and so its becoming a Soviet satellite would have constituted a major kink in Beijing’s long-term planning.

But that does not mean there was no Cold War skulduggery going on.

The Chinese may have been content to play the long game and wait for the handover at the end of Britain’s land lease, in 1997, but they also wanted to know what the British knew. From the early 50s to the mid-60s Little Sai Wan was British intelligence’s signals station (now Siu Sai Wan and a housing estate).

Operated by Britain’s Government Communications Headquarters, it was the biggest listening station in the Far East, sharing intelligence with Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the US. So it was bad news for the British when, in 1961, a PRC spy ring was uncovered in Hong Kong that included Chan Tak-fei, a translator working at Little Sai Wan, who had been passing information to China for several years.

In the 1970s, British prime minister Harold Wilson may have condemned America’s war in Vietnam and refused to send British troops, but Little Sai Wan monitored North Vietnamese radio communications and passed the intelligence gathered along to Washington. Information from Hong Kong was used to help American B-52s target locations in North Vietnam for devastating bombing raids.

Ultimately, it was decided that Little Sai Wan was too insecure an operation, and the final nail in its coffin, so some said, was when specially hired deaf-mute cleaners were caught reading highly classified secret documents.

In Hong Kong, you can never be sure who can be trusted. And the reasons remain the same.

It was the 17th century English statesman Sir Francis Bacon who was supposed to have coined the phrase scientia potentia est, the Latin aphorism for “knowledge is power”. Unsurprisingly perhaps, Bacon himself was reputedly a spy for Queen Elizabeth I.