- When Uli Sigg donated the bulk of his Chinese contemporary art collection to Hong Kong’s M+ museum, he had no idea of the controversy it would cause

Art collector Uli Sigg, a keen hunter in his youth, feels he is the one trapped these days, by the ping-pong dialectics of global politics. Targeted by pro-Beijing nationalists in Hong Kong for a collection that some perceive as “anti-China”, the Swiss businessman says the two Koreas are upset with him, too.

Last month, an exhibition, “Border Crossings: North and South Korean Art from the Sigg Collection”, opened near his home in Bern, Switzerland. South Korean lawmakers have been critical of their government for sponsoring an exhibition they perceive to contain North Korean “propaganda”. The North Koreans object to a painting titled Two Great White Sharks (2014), by Chinese artist Feng Mengbo, depicting dictator Kim Jong-un peering into a shark tank.

There has even been an investigation into whether the 75-year-old ex-diplomat – he was the Swiss ambassador in Beijing from 1995 to 1998, a role that covered not just China, but also North Korea and Mongolia – breached United Nations sanctions by purchasing North Korean art (he was cleared). Neither of the Koreas’ embassies in Bern accepted an invitation to the opening.

Now Sigg is in Hong Kong for the last stage of gifting his contemporary Chinese art collection to the city, a drawn-out and controversial saga that has taken nearly a decade.

Back in 2012, he donated 1,464 works then valued at HK$1.3 billion and sold an additional 47 pieces to the future M+ museum for HK$177 million. The museum’s founding director, Lars Nittve, called the group of works by 350 artists a “national collection of global significance”. A mainland Chinese author of a book on Hong Kong art history disagreed, saying M+ was reflecting a “postcolonial culture in the city that fawns over anything Western and is obsequious to foreigners”.

The much-delayed M+ building, designed by Swiss firm Herzog & de Meuron, is finally nearing completion, and most of Sigg’s Chinese collection has arrived from storage in Switzerland. Some pieces have been taken out of their crates and hung for a special Art Basel exhibition for VIP guests this week before the museum’s official opening this winter.

Chinese contemporary art prize favoured video – is painting dead?

The grievances did not stop at works that could be seen to be “insulting to the nation”. The same critics of Ai’s work combed through the online museum catalogue and were outraged by works that feature nudity and sex, such as Li Zhanyang’s explicit Monk and Nun (2006).

Does Sigg have the power to revoke his donations if the museum were to remove controversial pieces from the collection, or keep them hidden from public view?

“No,” he says. It was a short and straightforward contract with fewer than 30 pages, he adds. “It is a donation, so why should I impose myself and dictate terms for the next century? I was given the option to withdraw if the museum wasn’t open by 2019, but in late 2018 I was approached to re-discuss that clause.”

There will be three rotations over roughly three years so that people can get a sense of what the collection is about, and the museum has to dedicate a minimum of 5,000 square metres to displaying the collection during that time, and ensure that a certain percentage of it has to be exhibited at all times, not just at M+ but anywhere in the world.

M+ also agreed to take over the Chinese Contemporary Art Awards, founded by Sigg in 1998, and rename it The Sigg Prize.

Sigg says he did not foresee any call to censor his collection back in 2012, when he decided to send the art to a Hong Kong public museum. After all, “in 2012 the trend was still for China to have more freedom”. He does not think the rotation and display agreements will be broken. But if they are, he says, he is ready to sue.

Critics say that the perspective of M+ is too “Western” because its foundation collection has come from a Swiss businessman who has played a major role in promoting the kind of Chinese contemporary art that satisfies a Western liberal democratic appetite with an anti-authoritarian flavour.

And then there’s Ai, the lightning rod for the anti-M+ camp, the most famous of China’s political artists who has had major solo exhibitions in the West ever since his first meeting with Sigg, in 1995.

Everyone talks about that one photo by Ai Weiwei ... But it is one of four [related] pieces in the collection – the series also includes the same gesture made in front of the White HouseUli Sigg, who has donated the bulk of his Chinese contemporary art collection to Hong Kong’s M+ museum

“He wasn’t even practising as an artist then,” says Sigg. “He was more of an enabler, author and curator. When we met I sensed he was a person with much depth. We liked each other instantly and became friends.”

As Ai would say in the 2016 documentary The Chinese Lives of Uli Sigg, by the German-born Swiss director Michael Schindhelm, Sigg was “the maker” of Ai’s career and responsible for introducing him to Harald Szeemann, the influential curator who took Ai’s works to the Venice Biennale in 1999. (China did not have an official pavilion at the world’s most important art showcase until 2005.)

In that same documentary, Ai also said he tried to talk Sigg out of donating his collection to Hong Kong. “I was personally totally against donating the art to anywhere in China. You might as well have thrown it into Sursee lake,” he said, referring to the body of water near Sigg’s 17th-century home in Switzerland.

Ai hasn’t exactly said “I told you so” but the artist, who now lives in Cambridge, Britain, and has been outspoken about Hong Kong politics, indicates as much in recent media interviews over the calls to purge M+ of any art deemed anti-China.

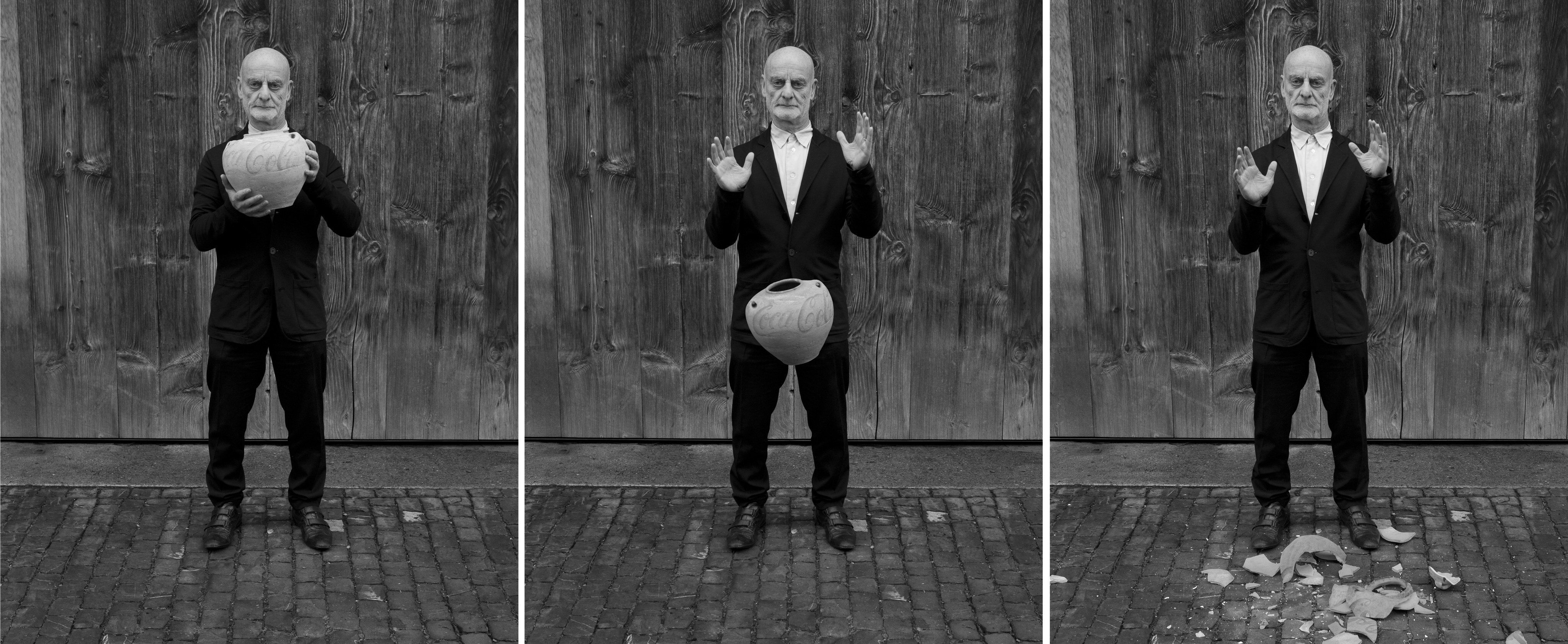

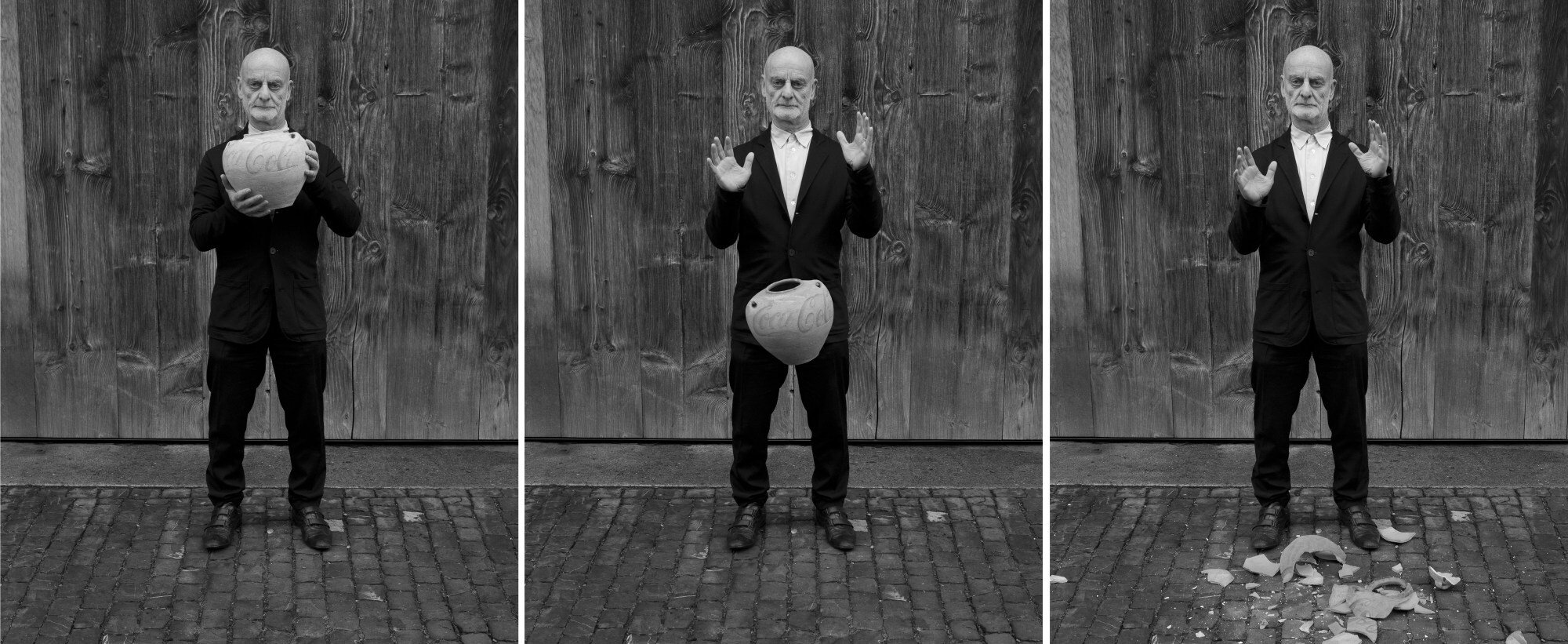

As of now, sources say at least two of Ai’s important works in the Sigg Collection will still be given prominent positions in the museum when it opens in the winter. One of them is Whitewash (1995-2000), 126 ancient earthenware jars that Ai had painted over, supposed to be arranged in rows on the ground of the large, Level 2 gallery dedicated to the Sigg Collection. The second work is Chang’an Boulevard (2004), a video capturing the contrast of extremes within the capital.

Sigg hopes that the “anti-China” label will dissolve as soon as people have a chance to see the huge variety of art in the “encyclopaedic” archive compiled since the late 1970s, rather than a personal collection based on his own tastes.

“Everyone talks about that one photo by Ai Weiwei,” he says. “If there is only that one photo I would consider it to be a stupid gag and I wouldn’t ever collect it. But it is one of four [related] pieces in the collection – the series also includes the same gesture made in front of the White House.”

Sigg has also amassed socialist realism oil paintings that the Communist Party commissioned to promote patriotism and the idea of a socialist utopia. Paintings such as Sun Guoqi and Zhang Hongzan’s Divert Water from the Milky Way Down (1974), which shows rosy-cheeked, beaming men and women looking as if they were having the time of their lives as they construct an aqueduct in a snowy landscape.

Sigg explains that soon after his first visit to China, on business in 1979, he began to look for Chinese art with “an originality of form” that would capture the enormous changes that began with the country’s opening up under Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms. But it took him a while to find any art that looked “new” to him.

“I didn’t collect any at first. That was the moment when artists in China were again able to carry out what they wanted to paint for themselves,” he says. “Then, in the 1990s, the art was no longer derivative. Chinese artists had found their own language and I wanted first to collect for myself. But then I decided to collect for archival reasons. That’s why I also bought hundreds of socialist realism posters and around 10 important oil paintings that were Cultural Revolution art from the 1970s.”

“Artistic innovation can only result from independent thinking. Artistic creativity is not the same as technological innovation. China proves that it has a lot of creativity, the kind of creativity related to functionality. This is drawn from strong motivation other than a desire for freedom. You don’t have to know that people were killed in 1989 to write good software,” he says, meaning that technical innovation can be achieved in an authoritarian environment but artistic creativity is much harder.

Sigg was not in Beijing on June 4, 1989. He had returned to Switzerland to marry his wife Rita, a dermatologist. He was there in the months leading up to that tragic day, however, and remembers Schindler China – the first foreign joint venture in China that he helped set up – sending a delegation to join the protests. By the time he got back, everything had changed. Mourning had to be done in private and freedoms were vastly curbed. He kept a low profile in those days, because it was considered immoral in the West for anyone to do business with the regime at the time.

Is Beijing targeting M+ museum or just politicians looking to score points?

His uninterrupted engagement with China since 1979 helps explain the significance of his collection, and Pi Li, the Sigg senior curator at M+, joked during a preview of the collection at ArtisTree in Hong Kong in 2016 about “the most comprehensive collection of contemporary Chinese art in the universe”. Some would say that’s an exaggeration because there were others, from Hong Kong and elsewhere, who supported Chinese artists in the 80s and 90s, and their contributions were of great importance, too.

Hong Kong gallerist and curator Johnson Chang Tsong-zung organised the first major exhibition of Chinese experimental art, called “China’s New Art, Post-1989”, in 1993, before taking it on a world tour. The year before, Italian curator Achille Bonito Oliva had worked with Chang to select the first Chinese contemporary artists to exhibit in Venice for the 1993 Biennale. In Paris, the Centre Pompidou introduced some of the more conceptual Chinese artists to the world in its 1989 “Magiciens de la terre” exhibition.

In Hong Kong, too, another Swiss collector, Manfred Schoeni, had started visiting Chinese artists in the early 90s and had held an exhibition for Liu Dahong in 1992 at the China Club. By then, David Tang had already filled the new clubhouse with contemporary Chinese art.

Sigg, who continues to visit mainland China regularly for business, remains optimistic. “Maybe in 10 years everything will be shown. Maybe 20 years. I may not live to see the day but my gift is for the long run.” Meanwhile, he continues to collect art. “I have around 900 pieces of art made mostly after 2012. This is a more personal collection. Eventually, I’d like a museum to take most of it. I think M+ is interested in it. I will think about it.”