Trump, Brexit, climate change: John Lanchester’s The Wall takes on every important issue facing the world right now

- British writer’s fifth novel a superb study of fear of ‘the Other’

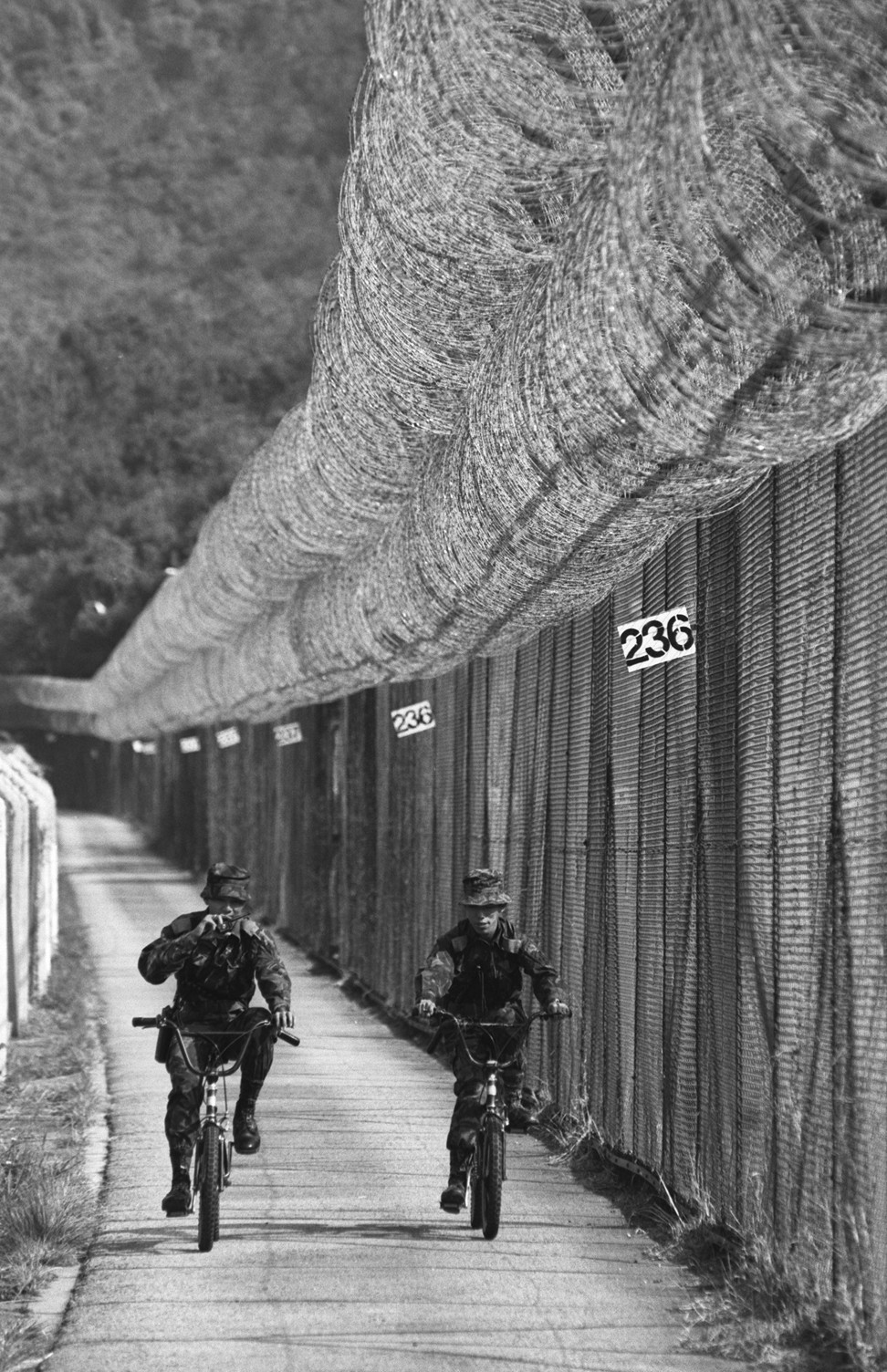

- Story builds a wall around the UK but the genesis of the tale is in the Lanchester family’s deep Hong Kong roots

“It’s not like it was talked about a lot, but it was there – that Hong Kong was built by refugees. It was built by people who fled China. People were trying to get into Hong Kong constantly and would die swimming across the bay. They would come over the border into the New Territories and would get caught and sent back, or got to Boundary Street and were allowed to stay. The way I processed that as a child was, well, if people are trying to get to where you are, then you are in the safe place.

“It’s better to be in the safe place.”

I’m supposed to talk to John Lanchester about The Wall, the acclaimed British writer’s superb new novel. And in many ways that is exactly what we do, in a nondescript office at the premises of his London publisher. The 56-year-old, who sports what appears to be a moth-eaten jumper lovingly patched with bright splashes of colour, talks expansively about his fifth novel, which has already been widely interpreted as a fable about, variously, immigration, Brexit, Trump, nationalism, refugees and environmental collapse: just about every important issue the world faces right now.

“I was in Hong Kong when [Tony] Blair was elected [prime minister of Britain], oddly enough,” he says, in one throwaway comment.

The reason for Lanchester’s interest is simple. Hong Kong was his home for most of his childhood. He left at the age of 18 to study in Britain, where he still lives and writes about everything from food to technology, sharp books on economics to award-winning novels such as The Debt to Pleasure (1996) and Capital (2012). The Lanchester family’s long connection with Hong Kong inspired the 2002 novel Fragrant Harbour and his subsequent memoir, Family Romance (2007). No fewer than three generations of his family lived in the city.

“[Hong Kong] was very much, then, a place people passed through. My dad had gone there as a kid. He’d been there since the 1930s. He was evacuated to Australia in the war. Much as in [Fragrant Harbour], my grandparents were interned in Stanley, then stayed on after the war. [The Lanchesters] went to Hong Kong in 1935 and left in 1980. That was unusual.”

Hong Kong permeates our conversation in other ways. It can be lighthearted or weighty, and sometimes both. As when Lanchester revisited his former family home, on Middle Gap Road, almost 20 years after leaving.

“The Mid-Levels round the back looking towards Lamma,” he says. “I was curious. It was a bit cheeky. I should probably have given some notice, but I didn’t know how.” Answering the door was a “polite and nice” youngish man, who, like Lanchester’s father, worked for the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank. “We immediately started talking about passports and identity. He had two kids. The question of their nationality was incredibly difficult and complicated. His wife was German. He was British but you don’t automatically get British citizenship any more. This was 1997, but it was exactly the sort of conversation that defines the modern moment – who you are and where you’re from.”

This blast into the past occurred on one of Lanchester’s final visits to Hong Kong. A planned trip in the early 21st century to appear at the Literary Festival was cancelled thanks to a bout of shingles, brought on by getting up at night to feed his then infant son and staying up even later to watch an Ashes Test cricket match. “It was properly stupid. I just completely broke my immune system.”

Lanchester’s bad timing proved strangely propitious. “Hong Kong was the festival I really wanted to do. Then literally that day, after we called them about the shingles, the Sars story broke. By noon, Hong Kong was the lead story in every newspaper.”

Lanchester is good company. He is funny, after a dry, rather hangdog fashion, which brightens even the darkest corners of our conversation – Brexit, Trump, climate change. His sentences spool out with a kind of rolling precision, being edited and refined as he goes. As his journalism suggests, Lanchester’s interests are catholic.

One moment he might be talking about the impact of having children in your 40s. “The funny thing was knowing for a fact that I would never recover. People would say you come out the other end. I remember feeling furious because I knew that, actually, that was a lie. I was broken in a way that you don’t glue back together.” The next, he provides a concise cultural reading of the Great Wall of China, which itself detours into appreciation of the admired Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges’ “Essay on Classification”.

Nevertheless, we rarely stray from Hong Kong for long. It surfaces again during some general discussion of illness. Lanchester recalls a family holiday before he left Hong Kong to read English at Oxford University. The family were staying at a cottage on Lantau owned by the bank. “They also had cottages in Fanling,” he adds. “Employees would have a weekend on a rota throughout the year.”

The wall is there for practical reasons, but it is also a very complete way of defining who the Others are. All you need to know about them is that they are on the other side. You don’t need sub-classifications. They are just Others

Lanchester was reading Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment while “swotting” for his Oxford entrance exams. “That’s a delirium anyway. But I was also coming down with the flu. As the book got madder and madder, I was getting iller and iller, but not realising I was getting iller and iller. By the end, my temperature was 103. It’s as if Dostoevsky gave me flu. Dostoevsky is like flu. It wouldn’t work if you were reading Anita Brookner. You would probably be cured if you were reading Jane Austen.”

This blend of wit and erudition is recognisable from Lanchester’s non-fiction – his scathing look at the 2008 financial crash, Whoops! (2010), or his wide-ranging guide to economics, How to Speak Money (2014).

Comedy of any sort is in shorter supply in The Wall, which occasionally feels like a black cloud of doom hovering over one’s head. The premise is simple but transfixing. In a near future ravaged by environmental catastrophe and riven by political strife, the British government has fortified the entire perimeter of the island nation with a forbidding wall, turning the country into a castle or prison, depending on your viewpoint. The purpose is to protect its citizens from the “Others” – Game of Thronesish shorthand for a vague conglomeration of enemies, some of whom seem intent on storming the barricade and destroying the nation.

In this, The Wall’s wall is at once inescapably real and a philosophical line in the sand. “The wall is there for practical reasons, but it is also a very complete way of defining who the Others are. All you need to know about them is that they are on the other side. You don’t need sub-classifications. They are just Others.”

Lanchester cites the wall separating East and West Germany as an example of what he means. “The Berlin Wall was a really powerful metaphor, and a structure around the whole of German society. But it also wasn’t. It was this physical thing and you got killed if you tried to cross it.”

The Great Wall is another “classic” example. “You look at it and say, ‘Hang on a minute, it doesn’t go round anywhere.’ It should be ‘The Slightly Below Average Wall of China’. But in historical records it is clearly incredibly important for defining Han Chinese identity. The wall is a classificatory system for ‘Chinese’ and ‘barbarian’. Almost all cultures have the same concept about ‘barbarians’. They are the people on the other side.”

Lanchester’s fictional wall is patrolled by “Defenders” such as our narrator, Joseph Kavanagh – Joseph K for short, in a nod to Franz Kafka. Like thousands of other young Britons, Joseph is conscripted to patrol the 11,000 mile barrier and fight off anyone who attempts to scale the defences. Lanchester’s devilish twist is that any Defender who fails to stop an Other is consigned into the void beyond the wall. Becoming an Other is, in effect, the worst possible punishment.

In this, walls serve a subtle double purpose. Demonising anyone outside the nation exalts everyone within. “There has to be something [inside] that is worth getting over for. It makes the people behind the wall feel as if their lives are very valuable. If other people want to come and take it, then it must be good.”

One of the things about Trump’s wall is, because America is a country built by immigrants, it does challenge what the whole idea of America is

Despite The Wall’s frequently exciting set pieces and enthralling second half, the overriding mood is bleak – comparable to the classic dystopias that have returned to bestseller charts. Lanchester squirms over the definition.

“I don’t remember ever having the same response to a book. I am insistently asked to put it on a specific shelf. Is it an allegory? Is it a dystopia? Is it a metaphor? Is it a parable?”

Reviews have been equally quick to draw political as well as literary parallels. I doubt there is one critic who has forgotten to mention Donald Trump’s promise – or threat – to physically partition Mexico from the United States.

“Trump said this tremendous thing about wheels and walls: they are medieval. Which is hilariously wrong, by several thousand years. He is literally 5,000 years out.” Lanchester, unsurprisingly, is not a fan. “One of the things about Trump’s wall is, because America is a country built by immigrants, it does challenge what the whole idea of America is.”

And yet he does acknowledge Trump’s crude rhetorical skill, if not his political or humanitarian acumen. “Walls just work. [Trump] has that ability to think laterally and in tabloid terms. People understand the image of a wall. They get it completely and fully. We all carry a picture of a wall in our heads. And yet, at the same time, the wall isn’t a metaphor. It’s really important to have that actual, physical wall.”

The other narrative popular with reviewers is Brexit. Lanchester is more hesitant at drawing direct parallels between the two. “It wasn’t a conscious influence, but it must be, I suppose. It’s too much of a coincidence.”

Lanchester has followed the countdown to Britain’s expected withdrawal from the European Union on March 29 with his usual despondent humour. “There is very little actual news. If you had been in a Rip Van Winkle-style coma from the day of the referendum you wouldn’t have missed anything. Two and half years; nothing’s happened. That’s genuinely strange, that sort of complete stasis.”

A staunch supporter of the Remain campaign to stay within the EU, Lanchester views Prime Minister Theresa May’s fraught and Byzantine negotiations as a kind of mirthless farce. He mentions the theories proposed by Leavers he knows in the financial sector.

“They are all saying, ‘Of course, there is a Remainer plot.’ To which I am saying, ‘I f***ing hope so.’ It would be nice to see evidence of it.”

Insecurity can take politics and society in some unexpected directions very quickly. Insecurity is usually a projection into the future

Both Trump and Brexit raise similar questions to those in The Wall. Why are people so afraid, and what, exactly, are they afraid of?

“Insecurity is the key. It’s like the 1930s. Insecurity can take politics and society in some unexpected directions very quickly. Insecurity is usually a projection into the future. While our politics were preoccupied by questions that were technocratic and economic, the conversation that mattered wasn’t happening. What was on a lot of people’s minds were issues about identity and culture and security. The economic conversation was on a parallel track.”

It is easy to mock the anxieties of Brexiteers and Breitbart supporters as out of proportion to reality. But as Lanchester insists, that doesn’t mean those fears are baseless. The Others are not, as I briefly suspected, a fiction and nor are they harmless. Even more ruthless individuals await Kavanagh in the great unknown beyond.

“It was important in the book to have an actual physical danger attached to the lives of the Defenders. It is not a metaphorical anxiety and insecurity. They genuinely could lose their lives.”

Lanchester is interested in how this threat shapes a world view. “People are frightened of losing their cultural identity. It’s an expression of that thing that as you get older, you look at the world around you and don’t recognise it any more. There’s always been an element of that for everybody, everywhere. But that’s more intense now. People look at the world and there are more people who are not like them.”

Does Lanchester ever feel this way? “I do not,” he says firmly. “I accept that not everyone is emotionally wired that way. A lot of people have the exact opposite feeling about immigration. For me it goes quite deep. If you are in a place that people want to come to, then your situation is not so desperate as those trying to flee.”

This returns Lanchester to Hong Kong – whose pivotal status between nations, cultures and hemispheres informs The Wall’s haunting second act. If the world portrayed in part one was cold, fixed and unyielding, part two plunges the reader into one of fluid uncertainty, as Kavanagh is banished and set adrift at sea. His growing uncertainty is given material form when he discovers a rag-tag community who live on a flotilla of rafts in the middle of the ocean. This unstable, fragile and even impossible home was inspired by another of Lanchester’s childhood memories.

“There was a floating village in Aberdeen and – it can’t still be true – there were people on it who had never been ashore. When people would come and visit us, we would take them to the floating village. There were old ladies who had never stood on dry land. There were restaurants and schools and everything.”

It was said a lot during the referendum that nobody feels British. That’s not true at all. And especially not true in that colonial and post-colonial diaspora

How Kavanagh in The Wall is changed by his own floating village remains unclear. But his efforts to adapt to liminality, ambiguity and life outside proscribed national borders finds an echo in Lanchester’s peripatetic experiences as a “post-colonial” boy.

“My grandfather was born in a different country from my dad. My dad was born in a different country from me. I was born in a different country than my sons. My grandad was from Yorkshire, my dad was born in Africa, I was born in Germany, and my kids were born in London. My mother is 100 per cent Irish, from County Mayo. I present as fully British. I am British. But actually that was more complicated than you might think.

“It was said a lot during the referendum that nobody feels British. That’s not true at all. And especially not true in that colonial and post-colonial diaspora. I had hardly ever been to England. I didn’t know what England really was. In Hong Kong, the engineers and police, the bankers were all Scottish. The governor was called Sir Murray MacLehose. He wasn’t from Guangzhou. He was 11 feet tall and used to wear this hat with peacock feathers. He really did look like a Hindu. That idea of Britishness being fluid was very present.”

Lanchester might be drawing a blueprint for the oft-mentioned “citizen of nowhere”, who popped up before, during and after the Brexit referendum. He might equally be describing a character that is destined to become a writer.

“Writing is a way of not being where you are, quite. Absence is very important in writing; it is one of the odd things about the modern appetite for readings and festivals and meeting writers in person. Writers by definition are people who prefer being absent. If you like being there and commanding the terrain, you don’t become a writer.”

The Wall’s publication means that Lanchester has been commanding public terrain whether he likes it or not. He draws a wobbly line between the John Lanchester who writes his books and the one who later discusses them. “It is slightly like being the straight man who is packed off to answer the questions,” he says.

What neither Lanchester can avoid are the grim prophecies contained within The Wall.

“One thing that happens with books like this, set in a dark version of an imaginary future, is the intention to prevent that future from happening.” The grimmest prophecy of all concerns the looming spectre of irreversible environmental ruin.

“I think we are right on the cusp. Trump will go. Brexit will be resolved one way or another. The thing that is permanent is the climate.”

China takes [climate change] massively seriously. People talk about Chinese world leadership. One of the ways it can do this is taking the lead on global warming

Here, too, is hope. Lanchester cites a report by the International Panel on Climate Change, which believes it’s still possible that the world can be kept to 1.5 degrees of warming – a small but important advance on two degrees.

“We have already had one degree, but [this forecast] shows a dramatically different map of the world. Hundreds of millions of lives saved, or saved from a horrible impact. That’s the difference between 1.5 degrees and two, which is the target of the Paris Agreement.”

Given Trump’s withdrawal from this same accord, is such a target feasible? Lanchester says we have no choice. “This is a last moment. Collective action on a global scale. We can still halt it at that level. The seas would get warmer for centuries, which is a frightening thought in itself, but it would in effect be saving the world.”

In the vacuum left by the US, Lanchester says China can – and indeed must – take a leading role. “China takes [climate change] massively seriously. People talk about Chinese world leadership. One of the ways it can do this is taking the lead on global warming.”

Lanchester suggests three reasons why China can make the difference. The first is what he euphemistically calls China’s “democratic deficit”, which means profound change can be accomplished quickly and efficiently. “It is an advantage in this case, where you have to do things that are unpopular and in a really massive, impactful way. And you have to do them everywhere.”

Secondly, China’s abundance of engineers and technocrats. Thirdly, China simply has no other option.

“You have a fifth of the world’s population essentially dependent on Himalayan meltwater. That’s what the Yellow River and Yangtze River are. They keep 1.3 billion people in food. China, the most populous country in the world, understands [climate change] and sees it as a critical thing. There are a lot of forces on the right side of this one; reasons for thinking we might do enough in time.”

This note of optimism proves contagious. Before we finish, Lanchester shares a final memory of Hong Kong – a lesson about what can be accomplished when populations cooperate for a common good.

“My first experience of refugees was the boatpeople. It was a big thing in my childhood.” In his last summer in Hong Kong, Lanchester volunteered at a Kowloon refugee camp. “They weren’t particularly welcome. Hong Kong was very paranoid about it. There was a worry about being swamped or overwhelmed by the numbers. The ecology was quite fragile, more so then. How many people can we take in? The boatpeople came and came, and kept coming – fleeing Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia.”

That’s exactly what the developed world did. It took 2.5 million people. Societies weren’t swamped. It’s a huge success story that those communities have thrived all around the world

This seemingly unsolvable humanitarian crisis generated a concerted response. “It’s an odd thing that the world has basically forgotten. At the time, people said, ‘We can’t take in millions of people.’ But actually, that’s exactly what the developed world did. It took 2.5 million people. Societies weren’t swamped. It’s a huge success story that those communities have thrived all around the world – 2.5 million refugees successfully resettled.”

Lanchester smiles at the thought.

“We can do it. And we know we can do it because we’ve done it before.”