Murder in Peking — two hot takes on a grisly 1937 cold case involving British teen

- Was Pamela Werner, who was 19 when she was raped, mutilated and left to die in a ditch, the victim of a trio of sexual deviants or a spurned wannabe suitor?

- Writer Paul French’s bestseller conjures the city’s oh-so Badlands while ex-police officer Graeme Sheppard taps 30 years of experience to assess the evidence

A semi-busy coffee shop in Newbury, a small market town about 80km west of London, is not the most obvious place in which to examine an unsolved murder that occurred decades ago in Beijing (then Peking). But Newbury is where I head, on a chilly winter day, battling the cold and Britain’s unreliable trains.

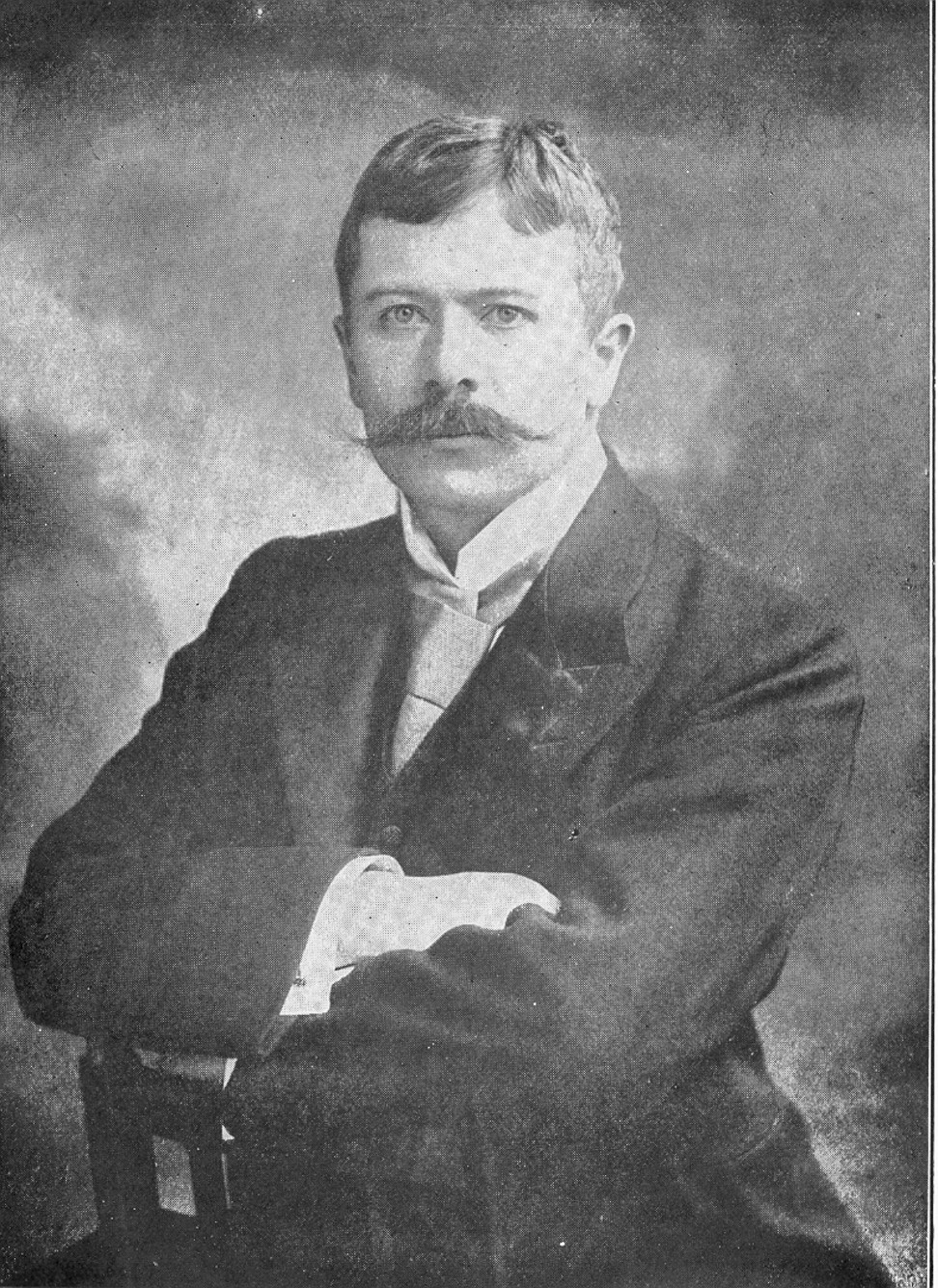

Luckily, patience is a virtue possessed by Graeme Sheppard, who has waited calmly for my arrival, though the word he uses to describe himself is “dogged”.

A Death in Peking: ex-police officer sheds new light on grisly 1937 murder of expat woman

Sheppard looks like a fitness instructor, possibly with a military background, or what he turns out to be: a recently retired police officer. He proves full of surprises, not least of which is that he started his working life as a keeper at London Zoo, in Regent’s Park.

“I left school at 16, which I have regretted ever since,” he says. “I lived and worked at Regent’s Park. It was a nice introduction to life; gave me good life experience.”

Recognising his ambitions to change the world were unlikely to be realised while looking after lions and tigers and bears, Sheppard joined the police force, where he remained for the next 30 years, largely with the Metropolitan Police Service and eventually with the Territorial Support Group, which specialises in public disorder and terrorist incidents.

“If you kill me,” Sheppard says at one point, “then all the CCTV between here and the train station, and everywhere else you might have gone, will be viewed.” The crime scene would be cordoned off, he adds, as would other locations of interest. There would be forensics, offender profiling and the now-extensive “digital follow-up”: thorough examinations of phones, computers and social media. This gathering of evidence occurs frantically in the “golden hour”, the period following the discovery of a body, when the chances of securing a conviction are at their highest.

Such experience has proved singularly useful in the third act of Sheppard’s working life: as an author, a profession for which persistence, attention to detail and an understanding of how humans behave in the most extreme situations are also assets.

“[Police] will see people when they are at their angriest – with you, with life in general. People are at their most desperate, are incredibly grateful that you have turned up and have saved their life. They cling to you. It’s a very strange job. It is difficult to explain unless you have been there.”

On January 8, 1937, a body was discovered in a secluded spot beside Beijing’s city wall. From the start, the details were both grisly and sensational. “[The victim] had been so badly mauled by stray dogs as to be unrecognisable,” reported British newspaper The Times.

The deceased was eventually identified as Pamela, the adopted daughter of E.T.C. Werner, a senior British diplomat, writer and scholar. Her adoptive mother, Gladys, had died in 1922, when Pamela was five.

The murder quickly grew even more macabre, with the revelations of mutilations inflicted on the body, including the removal of Pamela’s heart. While these details generated headlines around the world, they did not lead to a conviction, despite Werner Snr’s 20-year crusade to bring to justice the three men he believed were guilty.

“I don’t read true crime. I avoid it. Most police officers do. They’ve had a bellyful of it,” Sheppard says.

He made an exception in this case, however, because of an indirect family connection.

“My wife’s grandfather was Nicholas Fitzmaurice, the [British] consul in Peking at the time,” he explains. “He died in 1960 so she didn’t know him. I haven’t really met her family because they are spread out across the world.”

Sheppard’s immediate and instinctive response was to disagree with French’s findings, which tallied with those of Werner. Pamela, her father believed, was killed by Wentworth Prentice, an American dentist, Ugo Capuzzo, an Italian doctor, and Fred Knauf, a United States marine. Prentice is portrayed as the head of a sex ring – a group of mostly Western men who regularly raped and abused young women.

French’s theory is that Pamela was about to leave for England when she was seduced by Prentice, whom she knew as her dentist, and the promise of entrée into a glamorous adult world. When the trio raped Pamela, she screamed and fought back, so they struck her, causing the skull fracture that killed her. Mutilation of the corpse was part of the cover-up, the assumption being that Chinese would be blamed.

Sheppard’s dissatisfaction with this version of events was sufficiently intense to warrant three years spent examining the case, visiting the crime scene and poring over documents in archives around the world.

Throughout our conversation, Sheppard is respectful of French’s work, but regularly takes issue with its findings. “I would love to meet him and compare notes,” he says at one point. “I don’t want it to be a boxing match between me and Paul French.”

This has not happened but there has been some sparring in the British press. French has made much of Sheppard’s association with Fitzmaurice when defending his position: the consul, who acted as coroner following Pamela’s murder, does not emerge well in Midnight in Peking. “The incompetence and blatant racism/sexism of Fitzmaurice was too much for the Foreign Office even at the time,” French writes in one of several lengthy emails. Familial loyalty to Fitzmaurice, he suggests, not only motivated Sheppard’s reporting, it distorted the former policeman’s judgment

The idea that Fitzmaurice, or indeed any other British official in China, would obstruct or impede an investigation into the brutal rape and murder of a British subject, and let a lowly American dentist off the hook, merely because Werner was considered an irritant is absurd

French points to similar bad blood between Fitzmaurice and Werner, something Sheppard barely examines. This dates back to 1908, when the pair clashed over “[Hungarian-born archaeologist] Aurel Stein’s removal of paintings and artefacts from the caves at Dunhuang to the British Museum. This was, and, of course, remains, a highly contentious issue between the UK and China. Fitzmaurice defended the ‘right’ of Stein to take everything out of China without any compensation or consultation; Werner argued it was ‘looting’ and that Britain should work with China to preserve and study the caves in situ. Fitzmaurice won the argument, but hated Werner with a passion ever after, accusing him of ‘going native’.”

How Chinese bandits’ kidnapping of a blond British bride and her pet dogs became a global news story

In an email of his own, Sheppard asks French to provide the source for this story, since he can’t find one in Midnight in Peking. He adds, “The idea that Fitzmaurice, or indeed any other British official in China, would obstruct or impede an investigation into the brutal rape and murder of a British subject, and let a lowly American dentist off the hook, merely because Werner was considered an irritant is absurd. Never in my career have I come across even a whiff of anything like it. On the contrary, in such appalling cases everyone – police, courts, public officials – have all gone the extra mile to make things happen.”

All the family connection ensured, Sheppard says, was that he read French’s book to the end. “I realised that it was desperately wrong. I could not conceive, to put it politely, how the old man [Werner], idiosyncratic as he obviously was, had managed to succeed in identifying suspects living openly in a small community like Peking and the police would somehow miss that. British and Chinese police. There had to be more to it.”

So Sheppard set out to conduct his own investigation. “I have tried, as in a murder investigation, to cast my net wide, catch everything and not miss anything, and then sift and make sense of it. It is a complex tale over a lot of material.”

The resulting book feels like the work of an experienced police officer. Clearly written, methodical and well-sourced, it pores over the reliability of witnesses and the balance of probabilities, zeroes in on inconstancies in testimony and maintains a cool detachment. French uses similar research but he is more sure-footed than Sheppard in evoking Peking in the days before Japanese occupation and war changed the city forever. But French’s vivid prose also attempts to recreate scenes as a novelist might: “But Pamela refused to give in,” he writes of her final, desperate moments. “She had an independent streak that now flared up.”

For Sheppard, Pamela’s death presented any number of challenges, quite apart from its being a cold case that is more than 80 years old and already the subject of a bestselling book. Arguably, the major stumbling block is the absence of the original case papers.

“They would have told us all,” Sheppard says. “I suspect there is more to be found in China. Getting access to archives there is difficult.”

A more personal test was his own unfamiliarity with the country. He studied China and later visited Beijing to inspect the crime scene, at the bottom of the Fox Tower on the Tartar Wall. The area, remarkably, was little changed from 1937. What did he feel standing in a place he had so long imagined?

“It was a relief,” Sheppard says. “Going to the scene didn’t change anything. It confirmed everything. The place she was found was such an ideal spot for that sort of crime.”

Sheppard clearly empathises with the victim. He says the crimes that are hardest to leave behind are those that involve the mistreatment of children. “That’s where it becomes very difficult to detach. Cases where children were being abused by straight neglect – being ignored, where they receive no love nor care, and are just items of furniture around the house. That is more difficult to deal with than if they had been actually punched.”

Much of Sheppard’s case relies on discrediting the character of E.T.C. Werner.

“I have to choose my words carefully, because I do not wish to appear overly critical. Where Midnight in Peking went wrong is it followed only the line of inquiry by Werner. He was a very, very strange person. He did have a personality disorder; I just don’t know which one.”

Pamela Werner’s murder left a paper trail that reveals sorry tale of mysterious gun for hire Pinfold

Sheppard’s case includes a letter written back in 1913 by the British minister in Peking, Sir John Jordan – the Jordan who has a road in Yau Ma Tei named after him. Sir John describes Werner variously as “morbidly suspicious” and possessed of “quarrelsome idiosyncrasies”. Also, Werner had been prone to jealousy in his marriage and occasional violent outbursts. Arguably, his most grievous flaw where hunting killers was concerned had been presciently identified by his wife: “Once my husband gets an idea into his head there is no changing his mind,” she is reported to have said by a close friend.

The primary evidence of Werner’s monomania, according to Sheppard, was his unwavering conviction that Pamela had been kidnapped, raped, murdered and mutilated by Prentice, Capuzzo and Knauf.

“I felt confident that these people weren’t involved in the way Werner thought they were. Without sounding virtuous, there were now three people who were dead in their graves and were now being accused of being rapists and murderers. [Midnight in Peking] is a bestseller. One of the things that did motivate me was to try to get some justice for Prentice and Capuzzo and Knauf.

“Werner chose his suspects and then went about finding evidence. And he chose them because he was very much influenced by what he read in the press and what he heard in the coroner’s hearing.” Sheppard points to suggestions that the perpetrators were skilled in anatomy (hence Capuzzo, the doctor, and even Prentice, the dentist) and with a blade (Capuzzo enjoyed hunting; Knauf was a marine).

Two men sat either side of a scantily clad and possibly unconscious Western woman. Sun drove them to a remote access point on Wall Road called the Stone Bridge, he said, where he was paid and threatened before fleeing what, in the next few minutes, would become the scene of Pamela’s murder. The morning after, Sun said, he found blood on one of the cushions of his rickshaw.

Sheppard notes that Werner paid Sun for his testimony.

“This [rickshaw driver] gave a completely different account to the Chinese police in the days and weeks immediately after. He was after a reward even then. Once you’ve got a witness who has changed their story, you are not going to get them into court. Nobody should believe them. But Werner wanted to.”

Sheppard may disagree with both Werner and French about the guilt of Prentice, Capuzzo and Knauf, but he devoted considerable energy to tracing their lives from Pamela’s death to their own. These accounts often read like books in their own right: indeed, Capuzzo wrote an autobiography titled Chang Fu (Self-Criticism), which recorded his extraordinary experiences while imprisoned as a traitor and spy after the Communists came to power.

One of the things I wanted to highlight in the book was the Chinese were getting a s*** time constantly. Nobody cared. Not the Chinese police or the British

“I wanted to give a flavour of their lives because it gives a flavour of all those strange Westerners who were living out there. What on earth were they doing in China for decades? What kept them there?”

Did Sheppard find an answer? “The money they had went a very long way. They had a much higher standard of living: servants, gardeners, rickshaws. Maybe they had work opportunities that competition back home would not have afforded them.”

And what about the perspective of Peking’s Chinese, so often disregarded and disdained by those in the enclave?

“From what I understand, they were quietly, seethingly resentful. That was outlined in graffiti blaming the British embassy for everything, blaming British spies. Understandably so. One of the things I wanted to highlight in the book was the Chinese were getting a s*** time constantly. Nobody cared. Not the Chinese police or the British.”

Sheppard suggests police inaction, for several hours following the discovery of the body, was racist in nature. When Pamela was finally identified, all hell broke loose.

All of which brings us to the question: if Pamela was not killed by Prentice, Capuzzo and Knauf, who did kill her?

Sheppard’s prime suspect is Han Shou-ch’ing, a young student friend of Pamela’s. He admits he has unearthed no definitive evidence to substantiate this accusation, but instead has connected several leads that point Han’s way. Some are ingenious if not exactly watertight.

One of the best sections of Sheppard’s book concerns Edmund Backhouse, an eccentric and charismatic sinologist, translator, self-styled spy and confidence trickster. Backhouse has a characteristically scene-stealing cameo in Pamela’s afterlife, offering no fewer than three versions of the murder to three people. “What [Backhouse] did was take bits and pieces that he knew, and wove them into a good story that only he could present. He was an attention seeker. He knew no one could double check his claims.”

One of Backhouse’s tales proposed that Japanese soldiers had killed Pamela in revenge for the murder of Kisaku Sasaki by two British soldiers. A “personal and secret” letter written in 1938 by Allan Archer, who had succeeded Fitzmaurice as consul of Peking, reported that Backhouse had claimed Pamela had been lured into a Japanese restaurant by one “Tan Shou Ching, who had at one time been one of Pamela’s friends but had a grudge against Werner”.

Pamela’s association with Han is partly drawn from Werner’s own correspondence, which reports conversations he had with Richard Dennis, the British chief of police in the Treaty Port of Tientsin. Han and Pamela were friends, but Han wanted a romantic relationship, something that would have been taboo at the time and place. Werner admits to having broken Han’s nose. Apparently, he was one of several Chinese boys “waiting at the school gate enticing the girls to go with them to tea, cinemas, or even to their rooms”. Werner’s fury was such that he sent Pamela to school in Tientsin. Indeed, she had just returned to Peking after a long absence when she was killed.

On this vital point of her death, Sheppard can only hypothesise: Han met Pamela one chilly evening, made advances that were rebuffed and was angry enough to kill her. “[Han]’s association with Pamela went back years. Infatuation. Resentment. He was punched on the nose by Werner. That is a big loss of face. Maybe she gave him the brush-off. He might have come up behind her and smacked her in the head. He might have spent that walk chatting her up.”

That is a lot of “mights”, which is inevitable in long-unsolved cold cases. In the absence of hard facts, historians are forced to knit together hints and clues in all manner of reports – and sometimes reports of reports. Sheppard’s research into the removal of Pamela’s heart led him to a scholarly study that suggests it was a typical feature of Chinese murders. Does this make Han a more viable suspect than the Western trio? And if Han was on Dennis’ radar, why was the young man never arrested?

For Sheppard, Han’s disappearing act reinforces his theory. “The clincher is that he is the only person out of all those suspects not living and breathing and carrying on in Peking. He has run away.”

[Werner] could not admit to being wrong ... If Werner admits it’s Han, he has played a role in creating the rapist and murderer of his daughter

In which case, why did Werner himself never seriously entertain Han as a suspect? Given their own violent clash and Werner’s manifold prejudices, Han must have crossed his mind.

“We don’t know when it was that Werner got to hear about Han as a suspect,” Sheppard says. “I would not expect the police to inform him of the fact at any early stage of the investigation, but it may have been after he had already begun in his mind to form the hunter/surgeon/sexual-deviant theory of his own.

“[Werner] could not admit to being wrong. [Later] he had spent years creating a case and pointing the finger against certain Westerners.” And then Sheppard adds, as if the thought has suddenly occurred to him, “If Werner admits it’s Han, he has played a role in creating the rapist and murderer of his daughter.”

Sheppard accepts that his explanation would not secure a conviction in criminal court. “There is no witness, no DNA, no finger prints, no blood on his clothes. But if you go to civil court, on the balance of probabilities, he’s your man.”

After meeting Sheppard, I contact French. It becomes clear that nothing in Sheppard’s book has made him seriously reconsider his own findings.

French voices grave doubts about Han. Sheppard discredits Werner almost everywhere in his book, he argues, except when those same “tainted” documents justify his own theory. And that theory, French continues, is “completely full of holes” and “shows no understanding whatsoever of either Beijing or the time period, and just doesn’t add up at all.”

I have considerably more first-hand experience of murder scenes than Paul French. Blood does not ‘go everywhere’ once a person is dead and the heart has stopped beating ... By the time the mutilations occurred, minutes after death, or tens of minutes, her heart would have stopped and the blood would have already coagulated in situ

If Pamela were killed beside the wall, as Sheppard claims, where is the blood? “[He] butchers her horrifically all alone on a freezing night, drains away eight litres of blood into the Peking January ground (which would have been like concrete) and then simply disappears in a puff of smoke. I’ve yet to find anyone who considers it even remotely justifiable.”

When I put this point to Sheppard, I receive a long and gut-wrenchingly detailed description of what might have happened. “I have considerably more first-hand experience of murder scenes than Paul French,” he begins. “Blood does not ‘go everywhere’ once a person is dead and the heart has stopped beating. The cause of Pamela’s death was the internal effect of a fractured skull. She was also raped – probably while she was either unconscious, dying or dead. By the time the mutilations occurred, minutes after death, or tens of minutes, her heart would have stopped and the blood would have already coagulated in situ.”

One suspects French and Sheppard could argue over the morbid details for the rest of their lives – and indeed my own. My inbox is full of questions from French. Why did Prentice suddenly repaint his flat at 3 Legation Road that freezing January, opening all of his windows, unless he was attempting to hide something? French claims Prentice returned home with his accomplices after killing Pamela and later worried they might have left evidence. And why did the police never mention Han after the first week of the investigation?

My inbox is also full of responses from Sheppard. We have only Werner’s word that Prentice redecorated his apartment, and that word was written more than two years after Pamela’s murder. Han is named by the senior police officer Dennis.

And on it goes.

All the competing speculations about who did or did not kill Pamela only underline the short, sorrowful life of the girl herself. “We know so little about her,” Sheppard says. “She hadn’t had the time in life to develop herself and be a character.”

Indeed, it does seem to be her destiny to fade from view while other people (men, for the most part) argue about her fate – as marginalised in death as she had been in life.

We may never know who killed Pamela Werner. But how would knowing, in the end, change this most melancholy of stories?