How tourism changed China: Lonely Planet’s first guide to country reveals extent of its evolution

- Published 35 years ago, the book documents a nation barely recognisable today

- Despite being littered with flaws and short on practical information, the travel bible gave backpackers in the newly opened country something to talk, debate and bitch about

The guidebook is on the verge of joining spats and the rotary dial telephone as an object whose purpose needs explaining to children. But back in the 1980s, long before online travel forums were a twinkle in Daddy’s iPhone, young travellers sitting down to meals at shared tables in Beijing backstreet guest houses brought out neither smartphones nor tablets, but copies of a certain book.

In those pre-TripAdvisor days, when China had opened to independent travel without bothering to tell anyone, travel information about the country had to be bought in bookshops before leaving home, and updates to that information learned by talking to other travellers randomly encountered at restaurant tables.

High-speed rail helps Shenzhen make Lonely Planet best cities list

Updates were always needed. Conversations over dinner with newly made acquaintances would begin with, “Where in China have you been?”, “Where did you stay?” and “What was worth seeing?” but would then invariably turn to the inaccuracy and inconsistency of the guide.

Nevertheless, for most it comprised almost the sum total of their knowledge of China, which ran the gamut from the best place to find banana pancakes to the Mandarin for ice-cream (bingqilin). They clung fiercely to the guide for fear of otherwise drowning in a sea of incomprehension.

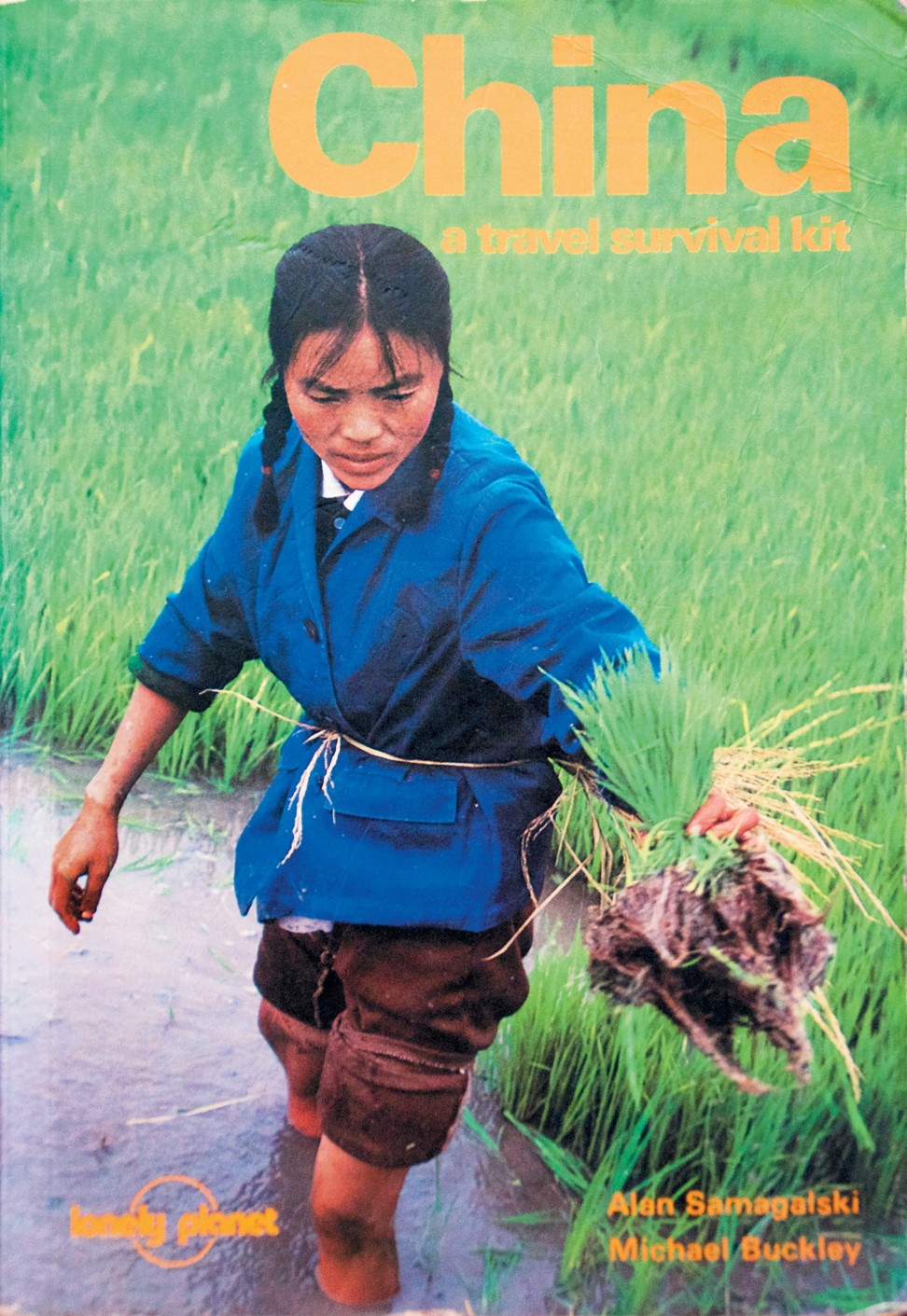

There was never any doubt as to which volume was meant by “the guide”. As far as budget independent travellers were concerned, there was only one: Lonely Planet’s China – A Travel Survival Kit, by Alan Samagalski and Michael Buckley, first published in 1984. Its cover showed a woman farmer in a jacket of uniform blue, with trousers rolled up, knee-deep in a paddy field of impossibly lurid green. Most readers would only ever fleetingly glimpse such a scene at a distance and from a train window.

Everyone had a copy, except for the odd individual, who, in his own opinion, was so cool he could be mistaken for a bingqilin. This guy would sit back with a patronising smirk and say, “I never buy guidebooks.”

Later, he would discreetly ask to borrow someone’s.

Copies that had spent longer in the country were creased, dog-eared and scribbled in, and exuded the faintly fruity odour that was then the background to daily life in China, especially when crammed with seemingly thousands of local people onto one of Beijing’s unreliable bread-bin-like buses.

But the mustiness rising today from surviving early editions of the book is nostalgia for a simpler China now almost completely lost. Then, knick-knack-laden Friendship Stores provided almost the only shopping opportunity, restaurants outside hotels were few and closed by 8pm, and the only nighttime entertainment outside the few big hotels and the occasional Chinese opera show was snooker played roadside on a table illuminated by a rare street light.

The guide is a more rewarding read now than it was then.

The loss by vandalism and utter neglect has been proceeding at such a rate that, on repeated occasions, buildings and historical monuments have actually disappeared while the authors were still writing about them

What those fumbling to master their chopsticks while carping about the inaccuracy of the book’s contents failed to understand was that for a China guide to be available in bookshops in the West was, by definition, for it to be out of date. Research, writing, editing, printing and distribution took far longer than the time it took for visa rules to change, entrance fees to rise and some freshly opened south China village to become the Next Big Thing for those wanting to just “chill out” – something for which 80s China, where almost everything was a struggle, was mostly unsuited.

These changes were typically unheralded, unpublicised and happened overnight, and it was unfair to blame the authors for that. Even as far back as 1935, writers L.C. Arlington and William Lewisohn’s In Search of Old Peking lamented the speed of change: “The loss by vandalism and utter neglect has been proceeding at such a rate that, on repeated occasions, buildings and historical monuments have actually disappeared while the authors were still writing about them.”

In the 80s, the problem was mostly that more was becoming available, not less – temples emerging from long periods as dormitories or storehouses, the government lengthening the list of open cities, and more private businesses offering services to visitors, especially around the foreigner-haunted guest houses.

But in many other cases there was evidence of the triumph of hearsay or laziness over solid research: “Apparently there’s a 100 yuan note but I’ve never seen it”, for example. Thanks were offered to a long list of other travellers for use of their notes, although with these contributions, unlike with TripAdvisor and similar sites today, the authors could presumably be confident that those whose notes they cribbed weren’t friends or paid accomplices of hotel owners.

The guide offered wise advice concerning the China International Travel Service (CITS), a government organisation supposedly designed to help foreign visitors not of Chinese descent. But CITS was just a soft employment option seized on by cadres of sufficient influence for their children, sometimes regardless of their ability with foreign languages. It generally exploited visitors’ ignorance and lack of Mandarin to help itself to as much of their cash as possible. As the guide pointed out, if CITS staff actually knew the answers to independent travel questions, they were rarely ready to part with them.

“The point is, that if CITS tells you that something cannot be done, that you cannot go somewhere or you can only go by such-and-such a means of transport – then check it out for yourself.”

But neither folk musician Samagalski nor footloose Buckley spoke any Mandarin, and only one of them had visited China before starting work on what would become, at 820 pages, Lonely Planet’s largest publishing project to date. As a result, they frequently failed to take their own advice and innumerable entries appeared to be no more than lifeless summaries of CITS brochure copy, lacking evidence that either author had indeed “checked it out for themselves”.

There was also a lack in such entries of essential practical detail such as opening times, transport information or entry prices. CITS sold foreigners tours for heavily marked-up prices, and wasn’t in the business of telling them how to do it for themselves. Readers who had bought the book precisely to do that were often left disappointed, even for sights in the most commonly visited cities.

Counter-intuitively, attention to detail in guidebooks only increases accusations of inaccuracy, and the authors would have perhaps been wise to leave out more than they did. “You can get a bus there,” stays true longer than, “Bus 5 runs every 20 minutes from outside the Jinjiang Hotel for ¥0.50.” But omission of any transport information for some rural sight simply suggested it hadn’t been seen.

Although frequently falling short on practical information, the guide was nevertheless often prolix. “Worth checking out” and the endlessly repeated “a good place to”, “a not bad place to”, or “an excellent place to” found on almost every page wasted time and left readers begging the authors just to get on with saying why a “place” merited attention.

Even in the heart of the capital, within howl-of-frustration distance of the Forbidden City, sights sometimes seemed to have received scant if any attention. The two-sentence entry on Beijing’s “Mahakala Miao” (a version of its name mixing up Sanskrit and Mandarin words) displayed the guide’s customary inattention to detail: “The monastery here is dedicated to the Great Black Deva, a Mongol patron saint. It’s located on the hutong running east from Beichizi Dajie approximately in line with the south moat of the Forbidden City.”

The “great black one”, an aspect of Shiva, is, in fact, sacred to Hindus, Sikhs and various Buddhist sects. More importantly, there are several hutongs (alleys) running east from Beichizi Dajie (a street), which were all clearly labelled even back then. But that was irrelevant since the routes to the temple are actually off Nanchizi Dajie, further south, and at the time, the decaying building was being used as a school and not open to the public.

Sometimes the dinner table critics would embrace this lack of professionalism, arguing that the book was written by “people like us”. This was a fine argument if you like to be represented in court by a plumber rather than a lawyer, or to have your car repaired by someone who has never held a wrench. The point of paying the book’s then substantial £9.95/US$14.95 price tag was for its expertise, not ignorance.

But the authors’ lack of qualifications and the rough and unready nature of the material could at least allow many of the diners to dream, not unreasonably, that they could also be paid to travel.

Considering China’s vast size, the task facing guidebook authors at the time was tiny compared with the same job today. Most of the country was then inaccessible and even the guide stated that there were a mere 29 places, from Beijing to Zhengzhou, that could be visited without an Alien’s Travel Permit out of “about 130 or so” officially open to foreign visitors. Yet this was still a colossal task for just two people.

First-time visitor Samagalski spent only five months in China, yet covered the country’s roughly 5,500km width, from the southeast coast to Kashgar, near the Pakistani border. With public transport so lumbering and slow, he must have been constantly on the move, and his every experience unavoidably cursory. Half a dozen writers working together might have covered the country more thoroughly and in time for the book still to be fresh when it arrived in the shops. To have just two on the road was like painting a large bridge: even before the job was complete it was time to start again.

Guidebook writing was mostly undertaken for a flat fee, and the quicker the travel was completed, the less of that fee disappeared in costs

The situation for writers was not as rosy as the diners might have dreamt. If any two travellers gathered together complained about the guide’s inaccuracy, when any two guidebook writers met they would complain about the lack of royalty payments. Guidebook writing was mostly undertaken for a flat fee, and the quicker the travel was completed, the less of that fee disappeared in costs. Many authors stumbled into the job quite accidentally, and it was rumoured that Lonely Planet’s co-founders, Maureen and Tony Wheeler, would pick up new writers in bars.

Tony Wheeler told The New York Times in 2013: “You couldn’t just look for travel book writers because they weren’t out there. There wasn’t such an animal. We just told people that if you turn up in a year and a half with a book, we’ll publish it, and we did.”

Yet across 80s China there were dinner tables full of travel writers manqué. A guidebook seemed a far more modest project than a novel, requiring no plot, character development or denouement, and apparently only limited expressive ability or acquaintance with English grammar.

But a backpacker might roll out of bed at noon then head downstairs for a lunch washed down with two bottles of cheap Chinese beer before deciding that it was by then too late to attempt to reach any of the limited sub-set of sights suggested by the guide. A dedicated guidebook writer had no such option. He would have risen early to reach some remote temple by public transport, visited several bus stations to translate their chalked-up timetables, and spent the rest of the day walking the streets in search of new budget accommodation, noting room prices and telephone numbers, and examining menus and peering over the shoulders of startled diners in the restaurants. It wasn’t glamorous, and preparing a guide in no way resembled a paid holiday.

Lonely Planet’s China readers would make their way to recommended guest houses, enter to find other backpackers poring over copies of the same guide and immediately feel reassured that the guide had led them to the best place – entirely circular reasoning. The best place was, in fact, often just round the corner; newly opened, cheaper, eager for business and as yet without the bad habit of marking up its other services to travellers lulled into a false sense of security by the presence of so many other guide readers.

But to find alternative accommodation required an ability to read characters, some spoken Mandarin to ask for details, and the time to do the research. A little knowledge of the language would certainly have relieved the authors of some of their frequently expressed mystification.

If the book was something short of a masterpiece of practical detail, it had no pretensions to literary merit, either. It was written with a breezy, cocksure, self-consciously cynical authority convincing only to the China neophyte. But luckily for publisher and authors alike, almost the entire available readership at the time knew nothing about China.

The interminable train journeys between cities, typically involving at least one night on board, ensured that often the book would end up being read from cover to cover – history section, language section and all.

The authors managed to conjure four opium wars out of the more familiar two. They let the Communist Party off rather lightly for the tens of millions starved in the Great Leap Forward and yet expressed considerable outrage at its contribution to the deaths of 2 million in Kampuchea. Their understanding of how much time China had spent being ruled by foreigners, let alone by a foreign ideology, was rather limited.

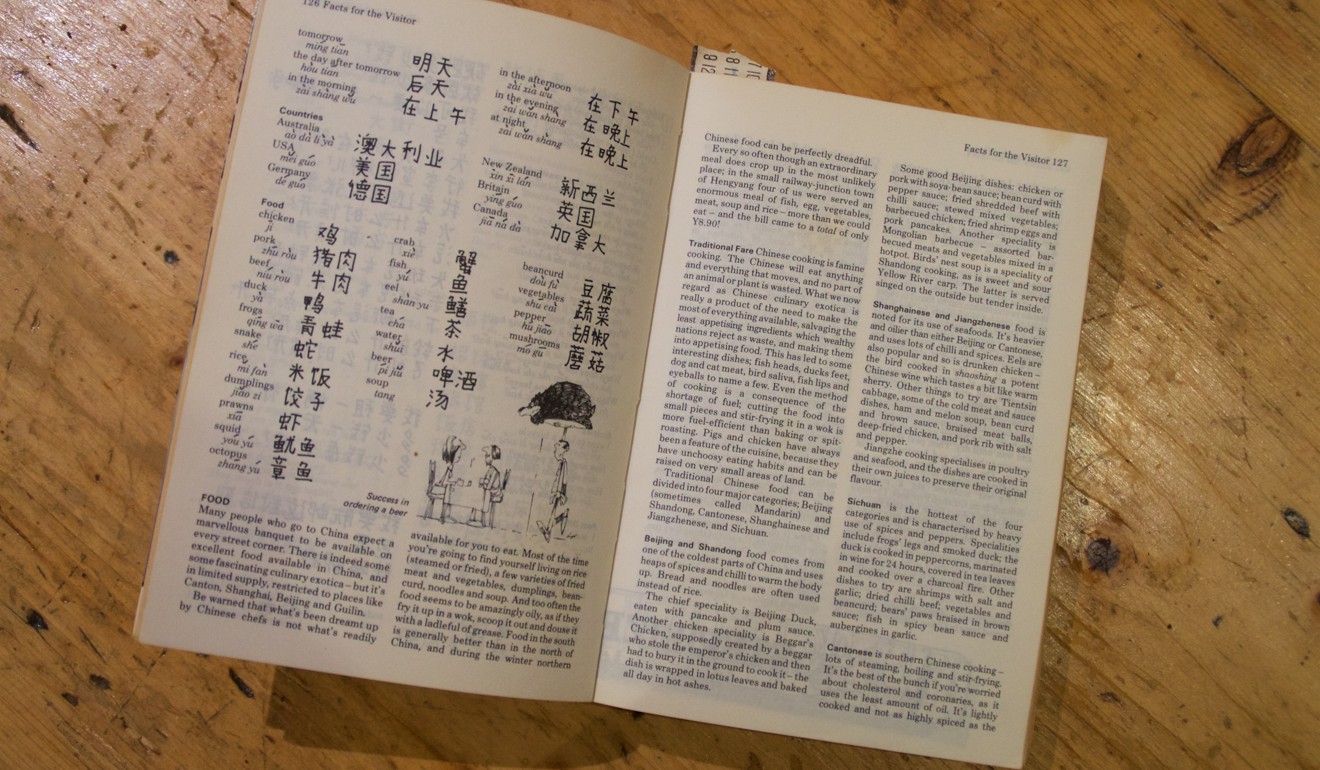

A fabulously garbled account of Mandarin discussed the matter of tones but went on to use a Cantonese sound to illustrate its explanation. And on Cantonese it commented that, “It is said to be the only language in the world that can’t be whispered – I’m told by a speaker of Cantonese that this is not true.”

Any credit due for inserting the Chinese characters without which any China guide is useless, and against which publishers nevertheless fight on cost grounds, was lost by having them hand-written in a poor and inelegant manner and in insufficient numbers to be of much use. The food section lacked dish names, and listed only 22 ingredients.

Looked at now, the book’s contents are often excruciating; set in living memory yet apparently in a culture that’s entirely alien. Did we really say that?

The book promoted an “us and them” mentality, and did little to encourage engagement. Its patronising tone was difficult to swallow even then. “The women are among the most flat-chested on earth,” was hardly a helpful observation

“A lot of people go to China expecting a profound cultural experience – and this has led to a lot of disappointment,” intoned the guide. True, 80s China wasn’t full of wispy bearded Mandarins, their hands thrust deep into copious sleeves, continually muttering quotations from Confucius, and it was the visitors’ fault if they expected any such thing. But the book promoted an “us and them” mentality, and did little to encourage engagement. Its patronising tone was difficult to swallow even then.

“The women are among the most flat-chested on earth,” was hardly a helpful observation.

“We all know the amazing effects of Polaroid photography on the natives – so you can easily set yourself up in the magic business in China.” Perhaps you should bring beads to trade, too?

“A yellow face and slant eyes will still get you cheaper prices in the Chinese hotels.”

This might have been true, but did they really say that?

(They did. Pages 113, 103 and 109, respectively.)

Dinner at the backpackers’ table would progress to an often fruitless pursuit of dessert, further personal experiences of other cities and sights being shared and notes quickly scribbled in the margins on appropriate pages. As the table gradually filled with empty bottles bearing the provincial brewery’s label, the diners congratulated themselves on being travellers, and not, they sneered, tourists, the target of mocking anecdotes in the book.

Being led to form a line around sights recommended by a single guidebook was inexplicably quite different from being led around them in a group by a single guide.

“Along the hippie trail [the overland journey taken by members of the subculture from the mid-1950s to the late 70s, between Europe and South Asia], there were certain places you all ended up,” Tony Wheeler told The New York Times. “If you knew someone travelling across Asia, you could sit down and wait for them; you might have to wait six months, but eventually they’d come in the door.” The near-universal adoption of his company’s guide meant the same became true of travellers within China.

Tours were not yet likely to have noticed some of the guide’s more rural selections, such as Yangshuo, mentioned as the terminus of the over-praised and overpriced Li River cruise through the karst limestone peaks of Guangxi province. Tours did reach it in large numbers but almost immediately mounted buses for the return to their starting point at Guilin, never thinking to stay in what was then one of the few smaller towns where that was permitted.

The guide fails to provide any lively description of Yangshuo’s charm in those days [...] But it still manages to inspire nostalgia for the town’s then secluded rural atmosphere, for whose disappearance the guide was itself partly responsible

The guide fails to provide any lively description of Yangshuo’s charm in those days, faintly praising it as “laid-back” and “a pleasant place” with “nothing to see”. But it still manages to inspire nostalgia for the town’s then secluded rural atmosphere, for whose disappearance the guide was itself partly responsible.

By day, Yangshuo was in easy biking distance of hills to climb for scenic views and of tiny villages where the arrival of an outlandish foreigner would bring a rush of every member of the population not busy in the fields. After sundown there was nearly total darkness and nearly total quiet, and it was possible to go out on the river to watch by lantern light as old men poled bamboo rafts lined with cormorants into mid-stream. They footed their charges into the water to make them fetch fish that would then be shaken from the birds’ beaks into a handwoven basket. Even then, this tradition was probably maintained only to earn tourism revenue, but it delighted all the same.

Afterwards it was possible to sit on a guest-house roof drinking unchilled beer and discussing where to go next while admiring the moonlight playing on a panorama of peaks, their outlines softened by mist rising from the river.

Those readers who had taken the book’s hint to pause in Yangshuo subsequently passed on more fulsome descriptions, which spread by word of mouth wherever budget travellers met to dine. The volume of visitors grew rapidly, and by the book’s second edition, published in 1988, there was already a choice of cafes with wry English names full of backpackers eating something resembling pizza and banana pancakes. As a result, when Chinese domestic tourism finally took off, Yangshuo was sold as a place to see foreigners doing foreign things on “Yangren Jie” – Foreigner Street – with megaphone-wielding guides pointing out the hapless traveller eating alfresco, frozen with fork halfway to mouth, taken unawares by the unexpected attention of two dozen citizen-paparazzi.

‘No book can do what a great guide does’: why you need a tour guide

Yangshuo’s old streets have been repeatedly redeveloped to provide more accommodation, and the “old” town newly expanded. The peaks all have entrance fees, and the once-silent evenings are disturbed by the distant boom and flash of a Zhang Yimou-directed son et lumière, and by the crowds who throng the streets purchasing fake Louis Vuitton bags. They sit at pavement cafes to eat distant relatives of spaghetti carbonara while fending off guides looking for clients for the next day’s trip. The bamboo rafts are now made of plastic tubes with garish garden chairs lashed to them, and are powered by noisy and polluting long-tail motors.

The town is “laid-back” no longer.

When it came time to pay the bill for the meal, there’d inevitably be discussion of the best black market exchange rates between yuan and foreign exchange certificates (FEC), a parallel currency for foreigners.

For foreigners, all services, such as seats on rattletrap trains, had to be bought with these bilingual notes, and at a price nearly double that paid by Chinese people in yuan – considerably more than double if black-market exchange rates were considered.

Although officially FEC and yuan had equal value, demand from Chinese for the FEC meant that these could be illegally sold at a premium. FEC were required to buy imported appliances at the Friendship Store and to obtain hard currency for any family member lucky enough to be allowed out of the country. Yuan could be used by foreigners for services not specifically designed for them, including entrance fees, street food and long-distance buses.

The guide recommended going to Guilin for black market exchanges – “They’ll just about change your underpants for you, buy cassettes, sell you railway tickets and swap you [yuan] for FECs at a premium” – but in most larger cities where foreigners gathered it was almost impossible to return to a guest house without being accosted with the words, “Hello! Change money.” Sometimes the money changers were ordinary looking women, but often the speaker was a young male with long hair, sunglasses and Cuban heels who stood out from the blue- and green-jacketed masses. He might as well have had a neon sign over his head saying “spiv” or “黄牛”.

The exchange rate quoted (“1-50”, for example) would be against 100 FEC, with grubby 10 yuan notes counted out discreetly around a corner. The guide wisely recommended counting the money received, but the newest arrivals would happily take what was counted out to them, and leave smug at having fought back against the institutionalised double-pricing for foreigners. In keeping with the counterculture tone of the guide, a blow had been struck against “the Man”.

Those who had spent longer in the country would know to hold on tightly to their FEC while carefully recounting the – usually short by 10 – yuan. The seller would count it again, fain surprise, hand back the pile and smilingly add an extra note. The most experienced travellers would check again, only to find themselves now 20 yuan short. Occasionally, frustration at being cheated (while cheating the government) would lead short-changed travellers to toss the handful of yuan into the air like confetti and stalk off self-righteously into the safety of the foreigners-only guest house.

Yunnan revisited: on the trail of late travel writer Bruce Chatwin

The evening would end early as staff began turning off lights to drive the foreigners out. A few more bottles of beer might be taken back to the room, but it was known that at dawn, the fuwuyuan (attendants) would be noisily coming on shift or returning from breakfast shouting and banging doors, indifferent to the slumbers of their guests.

Paying for the room or dormitory bed in advance – the only option – plus a damage deposit that was sometimes hard to re-obtain at checkout, earned possession of a plastic tag to show to the fuwuyuan, who retained keys to all the rooms on her floor in a large rattling bunch that was her badge of office. She would open the door every time it was required, walking many kilometres daily up and down the guest house’s dusty corridors.

Her office-bedroom cubbyhole would typically be empty as she’d be sitting knitting with another attendant on a different floor. Getting back into the room after dinner required tracking her down before she disappeared to bed herself.

But once travellers were tucked in, with the guide for bedtime reading they could be sure of nodding off.

Peter Neville-Hadley was inspired by his distaste for various editions of Lonely Planet’s China to become the author, co-author, managing editor, contributor, consultant or updater for 18 China guides and reference works for four publishers: Cadogan, Odyssey, Frommer’s and Dorling Kindersley.