Beijing’s Old Summer Palace: computer modelling brings back to life imperial garden destroyed by British and French troops

- Virtual reality has recreated the pinnacle of Chinese imperial garden and palace design

- Retired Tsinghua University architecture professor says digital recreation restores razed cultural landmark to former glory

The British high commissioner to China at the time was the 8th Earl of Elgin, after whom one of Hong Kong’s oldest streets is named. His decision regarding the emperor’s principal residence, the “Summer Palace” of Yuan Ming Yuan, was recorded in a dispatch.

Old summer palace replica a reminder of past glory and past pain

“We have dreadful news regarding the fate of some of our captured friends. It is an atrocious crime, and, not for vengeance, but for future security, ought to be severely dealt with,” he wrote. “Having, to the best of my judgment, examined the question in all its bearings, I came to the conclusion that the destruction of Yuen-ming-yuen [sic] was the least objectionable of the several courses open to me.”

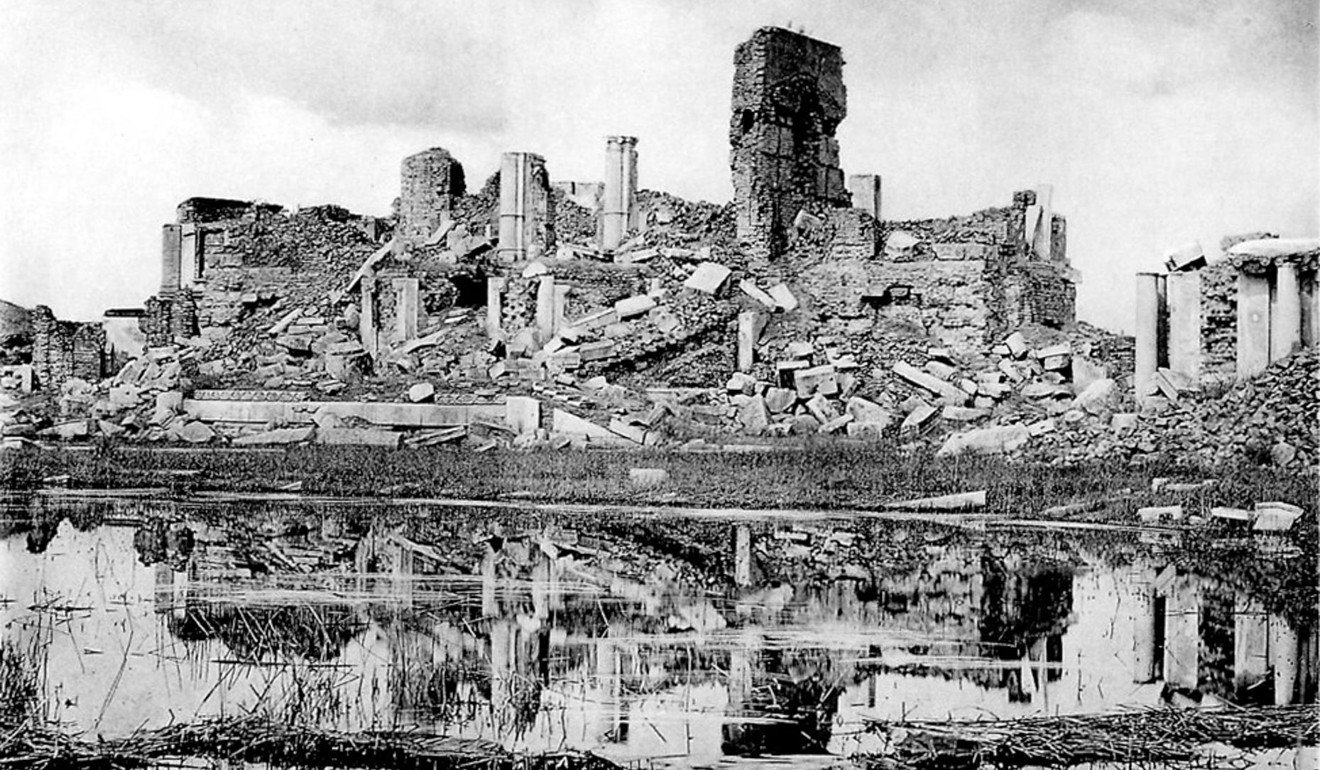

Yuan Ming Yuan, meaning “gardens of perfect brightness”, was the pinnacle of Chinese imperial garden and palace design. It took untold expense, the highest standard of artistry and 150 years to build. It took 4,000 men three days to burn it down.

“It was a sacrifice of all that was most ancient and most beautiful,” wrote Robert McGhee, a chaplain serving with the British expedition. “A man must be a poet, a painter, an historian, a virtuoso, a Chinese scholar, and I don’t know how many other things besides, to give you even an idea of it, and I am not an approach to any one of them. But whenever I think of beauty and taste, of skill and antiquity, while I live, I shall see before my mind’s eye some scene from those grounds, those palaces, and ever regret the stern but just necessity which laid them to ashes.”

Whatever Elgin’s feelings after the deed was done, he could not have foreseen how the ruins would be used a century-and-a-half after he left them. Some 8km northwest of Beijing’s Forbidden City, the carefully preserved remains in Yuan Ming Yuan’s 3.5 sq km have emerged as a centrepiece in a movement for “patriotic education”. And in answer to a national debate on whether to rebuild the complex or not, digital technology has been combined with partial restoration in a clever solution.

Guo Daiheng, a retired professor of architecture from Tsinghua University, is the foremost authority on the original structures. She has spent her life researching Yuan Ming Yuan, and leads an ongoing effort to recreate it in virtual reality.

“Yuan Ming Yuan’s moniker ‘garden of gardens’ comes from its countless scenic views,” she says. “You have mountains, lakes, pavilions and bridges juxtaposed in a never-ending sequence of perfectly composed panoramas.”

Today, this aesthetic can perhaps best be witnessed in the nine classical gardens of Suzhou, in Jiangsu province. Listed as a Unesco’s World Heritage Site, the ancient city’s landscaped treasures were the creation of rich mandarins in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties. Yuan Ming Yuan was of an even higher imperial quality.

Moving from beauty to function, Guo points out that because Yuan Ming Yuan was China’s centre of government (the Forbidden City was used for formal ceremonies), its vast expanse and hundreds of structures were conceived as a self-contained capital city, in which the emperor could live and work without ever having to leave. In addition to halls for receiving foreign dignitaries and senior mandarins, there were complexes for administration, temples (Buddhist and Taoist), libraries, galleries to house the imperial art collection, theatres, living quarters and so on.

This multiplicity has led French historian Bernard Brizay to say that the equivalent to Yuan Ming Yuan’s destruction in his own country would have been for an invader to blow up the Palace of Versailles, loot the Louvre of its thousands of priceless artworks and burn down the National Library of France.

All but a few of the handful of structures in the palace’s remoter reaches that survived Elgin’s 1860 rampage were finally destroyed four decades later, when the so-called Eight-Nation Alliance marched on Beijing to quell the Boxer Rebellion.

After 1949, in the early years of communist rule, surrounding villages were tilling Yuan Ming Yuan’s soil for food, and scavenging among its ruins for building materials. The People’s Republic’s first prime minister, Zhou Enlai, should be credited, says Guo, for designating the site as a protected area. Without this, she says, it would likely have been covered by government housing and factories.

Instead, visitors to the grounds at the turn of this century were confronted by a deserted wasteland, with piles of shattered masonry, paths choked by brambles and shrunken ponds overgrown with weeds. Today, however, it is a park that visitors flock to for guided tours, boating among lotus gardens and walks around lakes fringed with weeping willows and pavilions.

So what happened?

Most significantly, the change can be traced back to the Tiananmen Square crackdown of 1989, after which the government introduced a push for “patriotic” education, to foster national cohesion and support for the Communist Party. Guides from the Ministry of Culture now deliver scripted talks to visitors at Yuan Ming Yuan, on national humiliation at the hands of foreign aggressors.

Across the nation the message is repeated, in schools, newspaper articles, television costume dramas, documentaries and cinema. Jackie Chan’s 2012 film Chinese Zodiac, for example, tells the story of a treasure hunter out to recover 12 bronze heads of the animals in the Chinese zodiac (among the most famous treasures looted from Yuan Ming Yuan) from evil Western collectors.

The fate of Yuan Ming Yuan is a warning from a time when our leaders were weak, ineffectual and incapable of modernising the nation. They closed China to the outside world and so were oblivious to our backward state. When foreigners came charging in, we had no means to resist

Many in the West condemn this as propaganda, suggesting it is being used as a pretext for repression at home, and possible future aggression overseas. Chinese with a knowledge of history, however, blame the Qing dynasty for having been perilously out of touch with the modern world. To follow Brizay’s example, a present-day equivalent of the Qing’s behaviour would have been for Kim Jong-un, when faced with American ultimatums, to have tortured and killed US envoys sent to him in Pyongyang, and then sent their bodies back to Washington.

“The fate of Yuan Ming Yuan is a warning from a time when our leaders were weak, ineffectual and incapable of modernising the nation,” says Guo. “They closed China to the outside world and so were oblivious to our backward state. When foreigners came charging in, we had no means to resist.”

China needs to be an open nation, she continues. “We need to be strong enough to stand up to aggression. If nobody cares about their country, the same fate will once again befall China.”

As well as for patriotic education, Yuan Ming Yuan’s rejuvenation has been on the cards because of its size and location. Beijing’s rapid expansion means a site the size of 500 football pitches within its fifth ring road was sure, sooner or later, to be developed.

In the late 1980s, a debate emerged, with scholars on one side pushing for Yuan Ming Yuan to be rebuilt. In decisions made in 2000 and 2002, however, Beijing ruled for limited redevelopment, the aim being a park for leisure and education. Landscape features should be restored, it was decided, but no more than 10 per cent of the original structures should be rebuilt, the Huanghuazhen pavilion of the Western Mansions being one.

Some rebuilding was unavoidable because more than half of the original palace complex was devoted to lakes and connecting canals. To cross them, the emperors’ landscape architects constructed nearly 200 bridges, but only one remained (in an unusable state) when the overhaul got under way, in 2005.

Water posed perhaps the biggest challenge. Flooding was an annual problem in imperial Beijing but, since the late 20th century, the capital’s two main rivers have run completely dry because of drought. A dramatic drop in the water table meant that any water diverted into Yuan Ming Yuan would have quickly drained away. The solution was to line 1.33 sq km of the site’s dried-up lakes with an impermeable plastic membrane.

Yuan Ming Yuan’s physical refurbishment was completed in time for the Beijing Summer Olympics, in 2008. A decade on, it is one of the capital’s most popular parks.

Those who campaigned for full reconstruction have, by way of compensation, Guo’s achievements in the virtual realm. “I’m an architect by training, so computer rendering was an obvious solution,” she says. “We looked for everything we could find: old photos, maps, architects’ blueprints, artisans’ designs and written records. Some we found in the Forbidden City, some in the National Library, or further afield. We also consulted archaeologists who had excavated around the ruins.”

Eighty researchers in Guo’s Digital Yuan Ming Yuan programme, which was begun in the late 90s, worked for 15 years to build computer models of more than 2,000 structures before it finally went online on National Day (October 1) 2014. Visitors to the park can now take their mobile phone, iPad or virtual-reality headset to a ruined site, log on and view the splendid structure that stood there in the mid-19th century.

Guo was always opposed to those who argued for a full reconstruction. “Such people want to recapture old glory, but they don’t understand the importance of cultural relics,” she says. “A ruin like Yuan Ming Yuan is a historical record. In this case, that history includes its destruction by fire. If you rebuild, you erase the record.”

Guo is, however, eager to let Chinese people witness one of their country’s most magnificent achievements through recreation in the digital dimension. Thanks to modern technology, she believes, they can have it both ways.