Using Chinese seeds, American scientists thought they had created the dream tree. Then it grew into a nightmare

A handsome pear seedling, once embraced as the ubiquitous tree of post-war suburban America, has turned aggressively invasive from Texas to New York

Carole Bergmann parks her SUV in the Montgomery County town of Germantown, in the American state of Maryland, and takes me to the edge of an expansive meadow. A dense screen of charcoal-grey trees stands between the open ground and several houses. The trees are callery pears, escaped offspring of roadside trees in the neighbourhood. With no gardener to guide them, the spindly wildlings form an impenetrable thicket of dark twigs, with seven-centimetre thorns.

Bergmann, a field botanist with the Montgomery County Parks Department, extricates herself from the thicket andpoints out that what I took to be blades of grass are actually shoots of trees, mowed to be just a few centimetres high. There are countless thousands of them, hiding in plain sight. If it were not cut back once a year, the meadow would become like the adjacent acre upon acre of black-limbed and armoured trees worthy of Sleeping Beauty’s castle.

“You can’t mow this once and walk away,” says Bergmann, who began her 25-year career as a forest ecologist, but has been consumed by an ever-pressing need to address the escape of the invasive Bradford pear and other variants of callery pear, a species that originated in China.

The United States Agriculture Department scientists who gave the country the Bradford pear thought they were doing something wonderful. Instead, they delivered an environmental time bomb that has now exploded.

And it flourished everywhere – in poor soil, wet or dry, acidic or alkaline. It shrugged off pests and diseases. Millions of Bradford pears would be planted from California to Massachusetts and would come to signal the aspirations of post-war suburbia. Like the cookie-cutter suburbs themselves, the Bradford pear would embody that quintessentially American idea of mass-produced uniformity.

But like a comic book super-villain who had started off good, the Bradford pear crossed over, turning from thornless to spiky, tame to feral. Worst of all, it became invasive and is now an ecological marauder destined to continue its spread for decades. Generations yet to be born will learn to hate this Asian invader.

The Great Tea Robbery: how the British stole China’s seeds and secrets

It is at its most conspicuous in early spring, when it bursts into flower. Suddenly whole rural landscapes are lit up by its blossoms. Despite its eye-catching appeal, however, the Bradford pear is squeezing out native flora and reducing biodiversity across the US. Six months after the blooms appear, clusters of seedy berries invite birds to fatten up for winter. In the bird’s droppings, the seeds will germinate and advance, becoming ever more genetically diverse in the process and making the pear ever more adapted to its own spread.

The roots of the Bradford pear disaster go back more than a century, to when Northern California and southern Oregon were centres of US pear production. The common or European pear was a high-value fruit; in one Oregon county alone, Jackson, the pear industry in 1916 was worth a mind-boggling US$10 million.

With the orchards threatened by a new disease called fire blight, plant scientist Frank Reimer, working in Oregon, found that the callery pear, first brought to the US in 1908, was highly resistant and might be used as a rootstock onto which varieties of the European pear could be grafted. The much smaller callery fruit is used to make tea in China but is considered inedible.

To take his research further, Reimer needed lots of genetically rich wild seed from China, and he turned to David Fairchild, a dynamic young botanist in Washington, DC. (Fairchild is best remembered as the guy who helped bring Japanese cherry blossoms to the capital, by first growing 125 imported trees on his Maryland estate.)

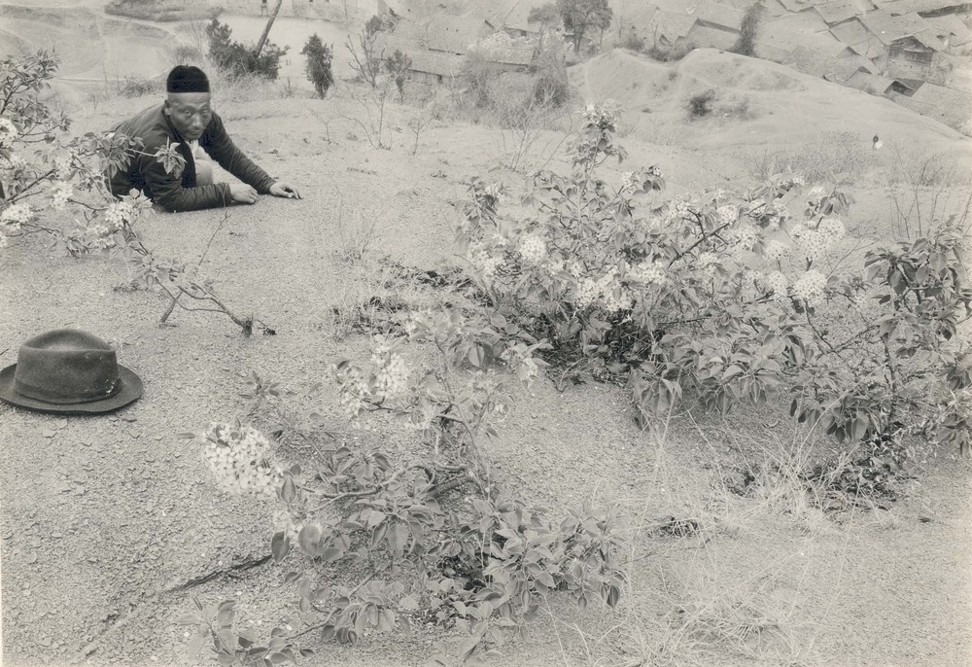

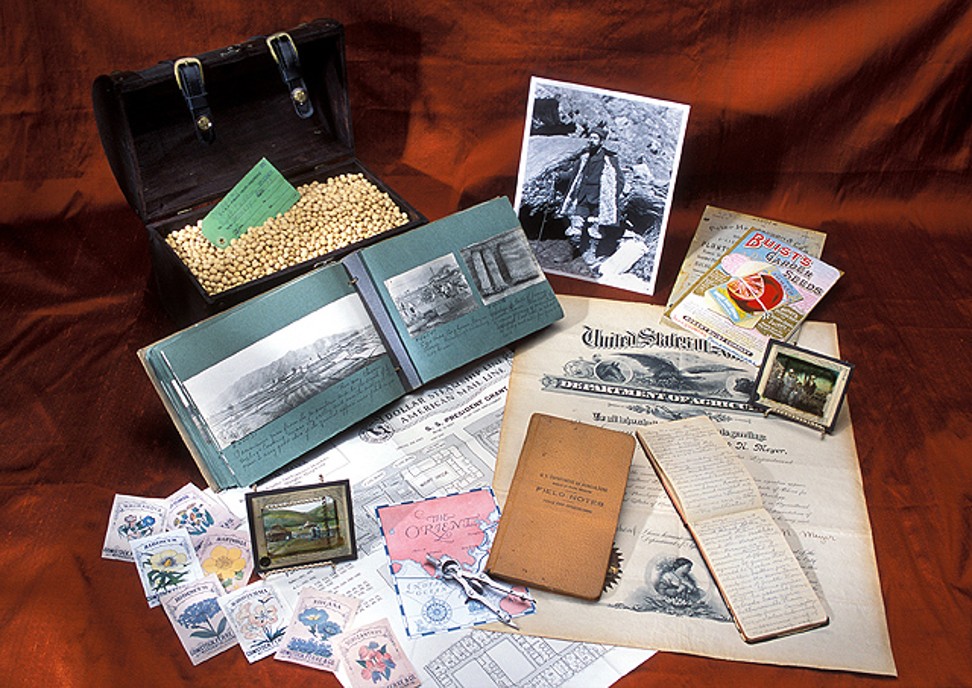

Fairchild headed the Agriculture Department’s Office of Foreign Seed and Plant Introduction. He travelled far during his career in search of new plants, but he relied on another explorer, Frank Meyer, in the quest for a “super pear”. Meyer, an émigré from the Netherlands (and who is best known for giving Americans the lemon variety named for him), had already explored China extensively when Fairchild asked him, in 1916, to visit the Asian country once more.

A haunting image of Meyer in China is captured in a 1908 photo. With a big black beard, sheepskin leggings and a staff, he is seen gazing into the distance from a mountainous, arid landscape. All about him, burlapped cuttings rest like tablets brought down from Mount Sinai. He is in his early 30s but looks older.

Meyer left Washington in August of 1916, travelling west to see Reimer’s pear trials in Oregon before departing Seattle bound for Japan on the last day of summer. Within a couple of months, he had sent six large shipments of seeds from Beijing containing pine nuts, walnuts and chestnuts, but no callery pear.

Fairchild, exasperated that Meyer was loafing in Beijing, urged him to make his way up the Yangtze River to look for the callery. “You must not leave any stone unturned to secure it,” he wrote. The correspondence between Meyer and Fairchild forms part of an archive of the Chinese expedition in the National Agricultural Library in Beltsville, Maryland.

Meyer eventually made his way to Yichang, a four-day boat ride from Hankou (now Wuhan) up the Yangtze, and he soon found wild-growing callery pears, if not in the extravagant amounts Reimer was seeking. “Altho’ not rare in the hills around here, the trees are very widely scattered, they are often quite small and as such produce individually but little fruit,” he wrote.

Many of the trees were stunted in dry, poor sites, but one remarkable aspect of this species soon became apparent. It could grow virtually anywhere. Meyer recorded pear trees on sterile mountain slopes, on the edge of a pond in wet soil, on screes, in bamboo stands and even in running water.

Having made arrangements for locals to collect and process the seed the following autumn, he set out to southern China in search of other plants, but got only as far as Hankou, where he took to his bed with “nervous prostration”.

He sent his first shipment of callery pear seeds to Fairchild in September, and the following month, he teamed up with Reimer and gathered about another 12kg of seeds – enough to grow a small forest. Reimer also collected on his own, before the two men went to Yichang in early November.

Another calamity was about to overtake Meyer, however, as China had become gripped by spreading internal strife, with factional warlords fighting for dominance. This kept him confined to Yichang while seeds and notes were isolated in Jingmen. “As I am writing,” he wrote in February 1918, “we hear the rickety noise of rifle fire.”

That spring, Meyer made his way to Jingmen to retrieve his pear seeds and baggage, and then took a steamer down the Yangtze back to Hankou.

On the evening of May 31, 1918, Meyer boarded another ship sailing downriver to Shanghai, where he planned to stay a month to escape the heat of Hankou and to ship his pear seeds to Fairchild.

That night, when the boat was about 50km upriver from the city of Wuhu, Meyer was seen by a cabin boy making for the deck. He was never seen alive again, and his body was fished out of the Yangtze four days later.

[Meyer] told me of his life’s struggles. Few people ever realised the tremendous battle that was raging in his soul

Samuel Sokobin, the American vice consul in Shanghai, conducted an investigation and reported that although it seemed Meyer had not been killed, it was “impossible to state” whether Meyer’s death was an accident or suicide. Signs point to the latter. After talking to the explorer’s servant and fellow passengers, Sokobin wrote: “It appears certain that Mr. Meyer had been depressed for some time.” He was 42.

Sokobin had Meyer’s body moved to the Protestant Cemetery in Shanghai and his seed collections sent to Washington. Reimer, in his time with Meyer in Jingmen, had come to see just how low he was. “He told me of his life’s struggles,” he later wrote. “Few people ever realised the tremendous battle that was raging in his soul.”

The seeds that Meyer and others collected ended up in Reimer’s test orchard in Oregon and the US Plant Introduction Station in Glenn Dale, then a rural enclave in Maryland’s Prince George’s County.

North Korea’s ravaged forests and the southerners ready to help replant them

In the early 1950s, a horticulturist at Glenn Dale named John Creech began to see the callery pears there not as a rootstock for the common pear but as an extraordinarily handsome and tough tree ideal for planting beside roads. He latched on to a single specimen that had been grown from seed that was not part of Meyer’s shipment but acquired soon afterward in Nanjing, as part of Fairchild’s same feverish search for callery pear seed.

The tree was 30 years old when Creech evaluated it, and he was struck by its vigour and its ornamental qualities. But a plant’s value lies, too, in what it is not. This one tree did not have the thorns of other callery pears; it was free of diseases and pests and held together in storms. In selecting this individual to mass-produce, Creech named it Bradford after the station’s former head, F.C. Bradford. This specimen’s resilience in storms belied what would become a major problem with its clones: tight branch-to-trunk angles and congested branching invited the limbs to break apart.

Happy with its performance in University Park (some of the original Bradfords are still there), he officially released the Bradford pear to the nursery trade in January 1960, and invited growers to obtain shoots for grafting onto callery pear seedlings. Each Bradford scion would be genetically identical, but the rootstocks each had their own DNA. This would cause problems later.

California’s succulent smugglers: plant poachers seed Asia’s desire for dudleya

For a few innocent years, the only thing working against the Bradford pear was its ubiquity. It was so golden that every nursery grower wanted to propagate it and every home builder and road-planning department wanted to plant it.

In 1966, Creech and colleague William Ackerman wrote that the University Park plantings had displayed very little fruit, in contrast to the situation back at Glenn Dale, where the whole zoo of callery pears – 2,500 seedlings – had produced “abundant fruit development” on similarly aged Bradfords. Their point was that if you kept Bradfords away from other pears, messy fruiting wouldn’t be a problem. But they clearly missed the ecological repercussions.

And in the University Park planting, they noticed something else that should have raised alarms. On a few grafted trees where the scion had failed, the rootstock had produced suckers that then bloomed. These flowers, with the help of bees, caused the “sterile” street trees to set viable fruit. Creech and Ackerman minimised the problem, saying it was highly localised.

It’s not a fix like building a bridge or putting down a road. Once you cut down a field of Bradford pears, they’re going to try to come back

Clues to the callery pear’s invasiveness are buried in a journal paper written by Ackerman in 1977, when he announced the introduction of another variety, named Whitehouse, chosen because it was more upright than Bradford and better suited to small gardens. But this selection was a fugitive from Glenn Dale, growing as a seed deposited by a bird on a neighbouring property; Bradford was one of its parents.

Essentially, the invasive callery pear had escaped the reservation.

Four years later, the US National Arboretum in Washington, DC introduced an even more columnar variety, named Capital. Meanwhile, commercial plant breeders were bringing to market other varieties of the callery pear, and by the mid-1980s, a dozen or so were available for planting. Many of these were introduced to get around the Bradford’s poor branch structure and propensity to break. Sterile by themselves, any two of these varieties together would produce a heavy fruit set for winter bird dispersal. The stage was set for the callery pear’s quiet occupation of the countryside.

Since 2012, Bergmann has led efforts to contain the callery pear on 232 acres, though it has been mapped on 425 acres within the Montgomery County park system alone, and may occupy countless more areas, she says. Crews have employed a number of tactics, including felling trees with chain saws, girdling their trunks with a blade and spraying the wound with a systemic herbicide.

“It’s not a fix like building a bridge or putting down a road,” Bergmann says. “Once you cut down a field of Bradford pears, they’re going to try to come back.”

Pest practice: the careless introduction of invasive species to Hong Kong

It seems that the Chinese tree has been a curse to those who tried to master it, though such wild trees in China are not invasive or particularly common. It is what US botanists did to the pear that caused it to turn against them: they brought the tree to an alien environment, selected one for unnatural propagation and then fused genetically different individuals together. They planted it intensively across the entire continental US, seeding its eventual spread. Today, it is a roving, free-range freak.

If Creech ever had regrets about introducing the Bradford pear, he kept them to himself. In economic terms for nursery growers, the tree was manna from heaven. By the 1990s, Creech knew of its structural ailments and the problem with self-seeding. But when these were raised, his response was always the same. “He would say, ‘Yes, the tree has had its problems, but it put a lot of kids through college,’” says Lynn Batdorf, the arboretum’s retired boxwood expert, who was a young horticulturist under Creech in the 1970s.

I sat down with the current arboretum director, Richard T. Olsen, and asked him to explain how Creech could have got the Bradford pear so wrong. Olsen says you cannot judge what happened without understanding the historical context. The mission of scientists like Creech and Fairchild was to find and manipulate plants in a way that solved a problem, met an unmet need or simply offered an attractive new plant for the American nursery industry and consumers.

Olsen recites Thomas Jefferson’s line: “The greatest service which can be rendered any country is to add a useful plant to its culture.”

For Creech and his peers working in the 1950s, the potential environmental effects were not part of the decision-making. “These people were pretty smart,” Olsen says. “Our values have changed.”

In addition, he argues that invasive plants have been enabled in their spread by centuries of environmental disturbance. “If we think in our forests we are dealing with a pristine habitat, we are deluding ourselves,” he says.

Meanwhile, Peter Del Tredici, a retired senior research scientist at Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum, says the concept of exotic invasive species did not even emerge until 30 years ago, even though European settlers recorded escaped plants as early as 1672.

“Without thinking much about it, we have globalised our environment in much the same way we have globalised our economy,” Del Tredici has written. He lives in the Boston suburb of Watertown, where he is seeing the first wave of callery pear invasion, young plants “in highly disturbed habitats where no maintenance has occurred”, he tells me.

In the US South, the march of the callery is much more evident. “It’s definitely starting to really become a prominent invasive in Alabama,” says Nancy Loewenstein, an extension specialist at Auburn University. “There are some areas that are just white in the spring.”

Bergmann, who is 67 and looking at the end of her career, says she owes it to future generations to try to contain the Bradford pear and other invasives in the hope that one day scientists can find a way to eradicate them.

It is a problem that Fairchild could not have envisioned a century ago, but the Bradford pear persists as a case study in how even the brightest scientific minds can be blind to what they might be creating long after they have gone.

In November 1917, Fairchild wrote to Meyer thanking him for the first batch of callery pear seeds he sent from China. “I believe,” he predicted, “these will hardly fail to have in them something of extreme value for this country.” The Washington Post