How one of Wall Street’s biggest insider trading cases was cracked in 1980s Hong Kong

United States’ case against a flamboyant Taiwanese investor made headlines around the world, and began the end of an era when short prison sentences sometimes made financial crime seem like a good bet

One evening in May 1986, Dennis Levine, a 33-year-old managing director in the mergers and acquisitions department of Wall Street investment bank Drexel Burnham Lambert, drove to the United States Attorney’s office in Lower Manhattan, went up to the sixth-floor reception area, and extended his hand to the two government prosecutors who were waiting to meet him. They weren’t interested. They bent him over a desk, frisked him and arrested him.

Not fully comprehending his situation, Levine seemed particularly worried that his BMW 633CSi would spend the night illegally parked on the street below. Wishing perhaps to be less conspicuous, he had driven it instead of his fire-engine-red Ferrari Testarossa. In a small courtesy that the lesser criminals with whom he was about to spend the night were likely not shown, the prosecutors moved it to the underground car park. The banker then spent the night in a holding cell, without his belt and Hermès tie, but still wearing his Gucci loafers.

Revealed: the soaring number of suspicious transactions in Hong Kong

Levine’s arrest, chronicled in Pulitzer Prize-winning author James Stewart’s bestselling Den of Thieves (1991), hit the news the next day and began what was then the biggest scandal in Wall Street history. His arrest was followed within weeks by those of two of his friends, Robert Wilkis, a vice-president at EF Hutton who had worked at Lazard Frères, and Ira Sokolow, a vice-president at Shearson Lehman Brothers.

A friend of Wilkis from his time at Lazard, analyst Randall Cecola, was being investigated and would later be arrested. David Brown of Goldman Sachs was arrested next, followed by Ilan Reich, a partner at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz, one of Wall Street’s top law firms.

Then, in November, Ivan Boesky, one of the best-known men on Wall Street in the 1980s, accomplished a rare feat by at once pleading guilty, paying US$100 million in fines and penalties, which equalled the annual budget of the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and still having a small fortune left over. He had authored a bestselling book, Merger Mania, a year earlier that explained how to get rich as an M&A arbitrageur, but left out the part about insider trading. When he was later outed as a stool pigeon, he became even more loathed than he already was.

Three months later, in February 1987, Richard Wigton, the head of arbitrage at Kidder, Peabody, was arrested, frisked and marched out of the securities firm’s office in handcuffs in front of his stunned colleagues, the first time a Wall Street executive had been made to do a “perp walk”. The idea came from the US Attorney for the Southern district of New York, Rudy Giuliani, who later dropped the charges against Wigton. Also arrested that Thursday morning was Goldman Sachs’ Robert Freeman, who would spend the next 2½ years trying to stay out of prison. He would be indicted, unindicted, indicted and – ultimately – unsuccessful.

The next day, Martin Siegel, who had cooperated for months with the Feds to build cases against, among others, Boesky, pleaded guilty to two felonies. He had been one of Wall Street’s golden boys, a top merger adviser who had recently moved from Kidder to Drexel, the firm whose junk bonds greased the financial wheels of much of the takeover express.

The rapid fire, high-profile busts brought insider trading on Wall Street into American living rooms, board rooms and classrooms for the first time. Starting with Levine’s arrest in May 1986, and running through to the sentencing of Drexel junk bond supremo Michael Milken in November 1990, news stories, profiles and various features and details about the cases, the bad guys – weren’t they rich enough? – and the good guys – they’re paid so little! – were regular, breathless features, on the front pages of newspapers, magazine covers and the nightly television news.

In his first trade, buying shares of an electric utility just before a takeover offer, [Fred Lee] made about US$1.6 million. Nine months later, he had already blown past Levine’s US$12 million in insider-trading profits and was on a trajectory to soon overtake Boesky

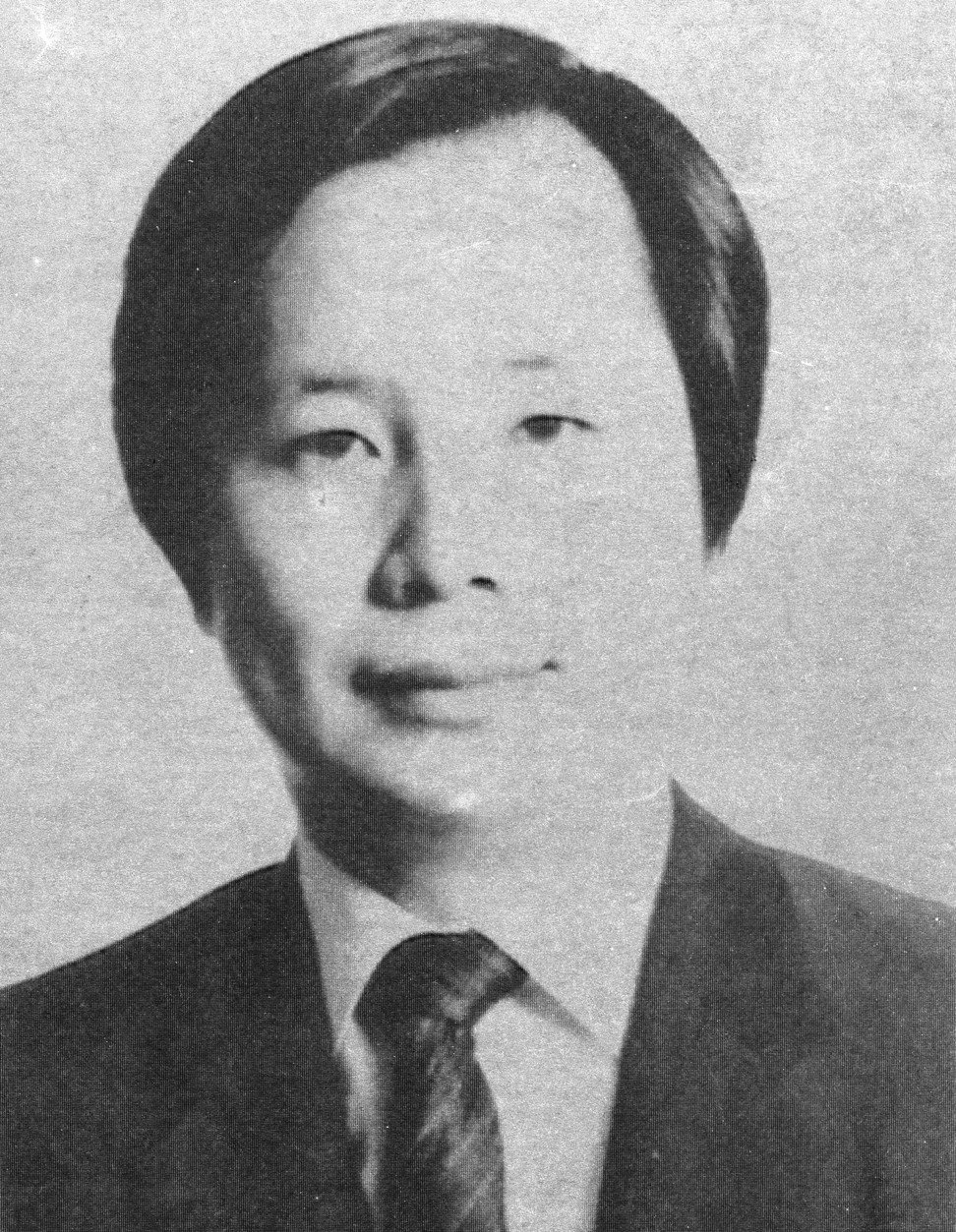

Into the maelstrom of high-profile, front-page Wall Street law enforcement, like snatch thieves at an FBI convention, stumbled two Wall Street nobodies: a 38-year-old Taiwanese bon vivant called Lee Chwan-hong and a 23-year-old investment banking analyst at Morgan Stanley, Stephen Wang Sui-kuan.

“Fred” Lee, as he was known in the US, befriended Wang in early 1987, handed him an envelope containing US$50,000 in New York’s Central Park a couple of months later, then started to buy shares and options in public companies just ahead of takeover announcements on confidential information Wang gave him.

In his first trade, buying shares of an electric utility just before a takeover offer, he made about US$1.6 million. Nine months later, he had already blown past Levine’s US$12 million in insider-trading profits and was on a trajectory to soon overtake Boesky as the most prolific insider trader in history.

Lee was the kind of client that American investment banks coveted as they pushed into fast-growing Asia in the 80s. Scion of a wealthy Taiwanese family, he had guanxi (“connections”). He was Western-educated, with an MBA from the University of San Francisco and a PhD from the University of Oregon. He had homes in Taipei, Hong Kong and McLean, Virginia. At a time when American investment banks were starting to put their own capital into leveraged buyouts, he was an attractive enough client for Morgan Stanley to invite him to invest in one of the firm’s leveraged buyout funds and enjoy the outsized returns that were practically guaranteed to follow.

He made the most of his favoured-client status, telephoning analysts in Morgan Stanley’s M&A department so often that he became a “nuisance”, pumping them for details about deals that they and others were working on. When Wang began volunteering to take Lee’s frequent calls, the others were happy to route them to him.

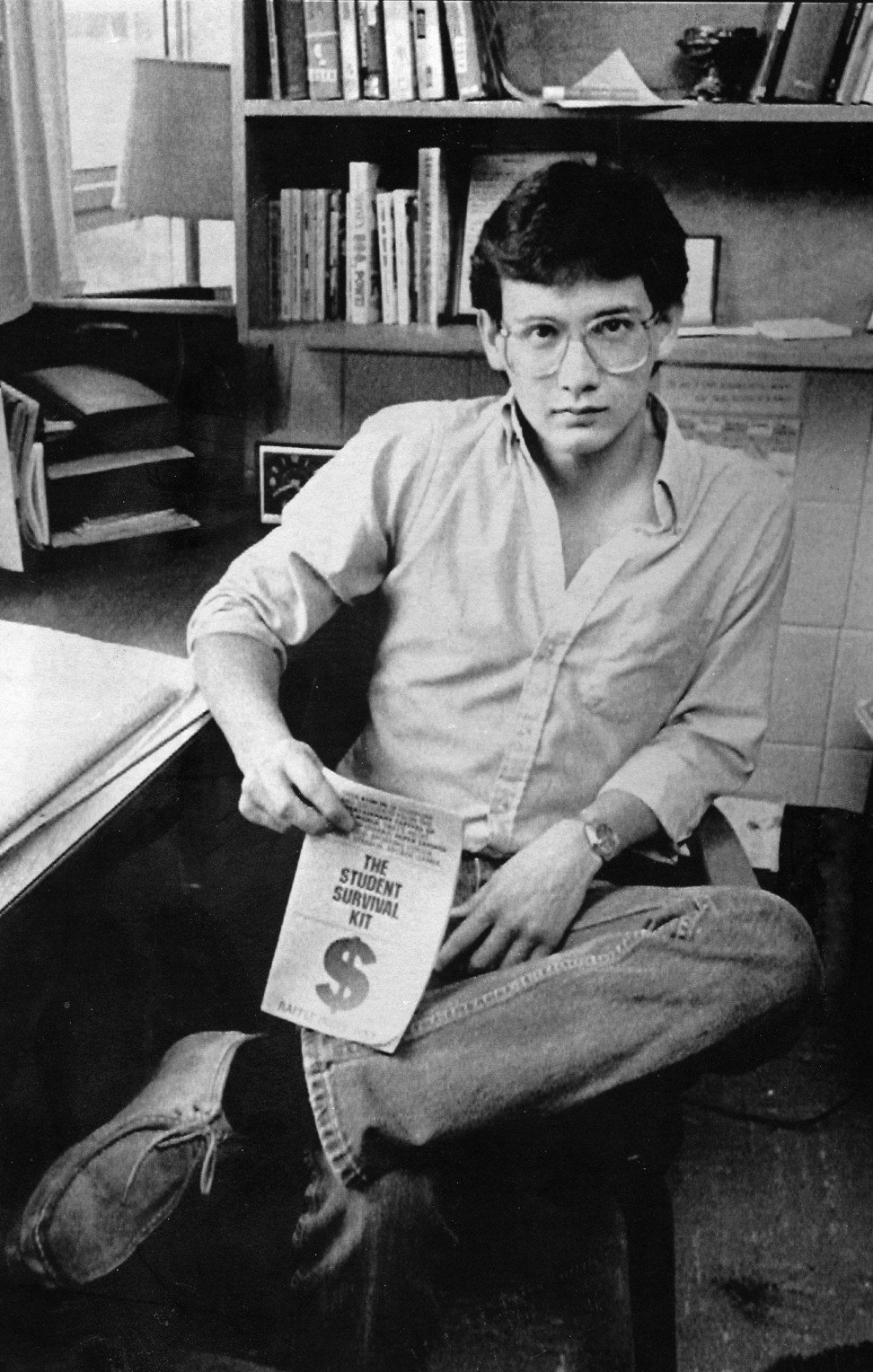

Wang was a young “go-getter” – athletic, musical and industrious. While other kids in his neighbourhood outside Chicago did odd jobs for spending money, teenage Wang started a business, even while working multiple part-time jobs.

“He was the kind of guy who could have 10 things going at once,” his high-school girlfriend told reporters.

While studying finance at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in the mid-80s, he made money running a couple of small student-service businesses. Interviewed by the Illini Times school newspaper, Wang said he planned to make his first million dollars by the age of 30.

He somehow talked his way into Morgan Stanley’s two-year analyst programme, despite not having completed his degree. He was working alongside the brightest graduates from Ivy League schools in the entry position to long-term big money in finance. Spending days and nights in the analysts’ “bullpen”, as the collection of cubicles that housed 100-hour-per-week drones on Wall Street was known, Wang was in a perfect position to pick up information that flowed through the camaraderie among young analysts at one of Wall Street’s top investment banks, and to monetise it.

Nearly half the businesses in Asia-Pacific have fallen victim to financial crime

In the days before disposable mobile phones, Lee introduced Wang to phone cards, which he used to make long-distance and international calls anonymously. When Lee was in New York, the two strolled together in Central Park, where Lee gave Wang wads of cash in envelopes. Two decades later, thousands from Wang’s Wall Street generation would be multimillionaires. For a guy who bragged that he’d be a millionaire by the time he was 30, Wang’s US$39,000 annual salary wasn’t going to be enough.

Gary Kaminsky’s job didn’t pay as well as Wang’s, but he loved it. A 27-year-old lawyer working at the SEC in Washington, he had started two years earlier after finishing law school. He was making US$33,000 a year, less than half of what he could have made if he had joined a law firm. But working at the SEC – a feared enforcement institution in the 80s – was like graduate school for lawyers. He was on the front line of high-profile securities fraud cases, investigating, interrogating and charging the bad guys. While his classmates were slaving away on the mind-numbing work of junior associates in a law firm, Kaminsky was busting scumbags; it had a certain appeal.

After finishing law school, Karen Beekman had worked in a law firm for two years, didn’t like it much and took a 50 per cent pay cut to work at the SEC because “that’s where the fun was”. The Boesky case was in the news and the SEC were the good guys, on the front line protecting US capital markets.

In early 1987, Kaminsky and Beekman had been assigned to investigate an insider-trading case involving a group of six friends from Brooklyn. In July 1986, just before firearm manufacturer Colt Industries announced it was going to be recapitalised, the six bought US$33,000 of Colt call options together. When the company announced the recapitalisation, its share price jumped 40 per cent and their US$33,000 options “investment” gave them a US$1.5 million gain. Some of the six had never traded options before. Their trades triggered an SEC investigation.

It took Kaminsky and Beekman months to put the evidence together, but they methodically built a case and prosecutors took the “tipper”, a lawyer named Israel Grossman, who had worked on the Colt deal, to trial in August 1987. It was the first insider-trading trial that consisted entirely of circumstantial evidence. Grossman was convicted and sentenced to two years in prison. But the case had not been a total victory for the government. By the time Grossman was charged, most of the illegal profits had been wired abroad, and three of the six traders had fled to Israel. These would be hard lessons, but well learned.

In early 1988, Kaminsky was reading the USA Today newspaper one morning when a blurb in an article about a takeover of E-II Holdings caught his eye: “[S]ome investors seemed to know what was coming: E-II stock jumped […] Thursday even though word of [the takeover] bid came out after the market closed.” Kaminsky turned to the stock tables. Sure enough, the day before the offer, purchases of E-II shares had skyrocketed. Maybe the buyers were just lucky – but maybe not.

In 1988, an SEC lawyer looking through a newspaper for signs of trouble in the securities markets wasn’t unusual. Kaminsky’s section chief, Tom McGonigle, a hard-charging ex-district attorney from Brooklyn, encouraged his people to look for red flags wherever they could.

The E-II purchases were just the tip of the iceberg. The traders had all bought the same shares or options, at the same time, hitting the same lottery 24 times in the past six months [...] They had amassed US$19 million in illegal profits

Kaminsky started digging. Building an insider-trading case was a laborious, time-consuming process involving stacks of clearing sheets, account statements, phone bills and other documents – often on microfiche – highlighters, rulers and pencils. The office shared one personal computer. Another one of the bosses, Hilton Foster, doubling as the resident tech guru, taught himself Lotus 1-2-3 and developed spreadsheets to analyse trading data. Still, the work required manual inputting and the data-crunching processing power was negligible.

A picture slowly emerged. A Hong Kong-based broker had executed the trades. Kaminsky contacted him: “Who’s your client?”

The reply was startling. The broker’s “client” was, in fact, about 30 clients, all from Taiwan, most of whom had also opened retail trading accounts at Charles Schwab & Co and Merrill Lynch in the US in the past six months, and all of whom had made the same trades. Kaminsky obtained their account statements.

As the workload grew, Beekman joined him again. The two were friends, often socialising with their spouses outside work. They had married a week apart during the Grossman investigation. What they saw amazed them: the E-II purchases were just the tip of the iceberg. The traders had all bought the same shares or options, at the same time, hitting the same lottery 24 times in the past six months. Within days of each purchase, the companies whose shares they bought jumped following news regarding a takeover. They had amassed US$19 million in illegal profits.

Hong Kong stock market slump spurs wave of insider share buying

Kaminsky and Beekman still needed to know who was feeding the traders their information – the tipper. They dug deeper. Morgan Stanley had advised at least one of the companies involved in every deal; they guessed they would find their tipper there. An odd coincidence also jumped out. One person had opened or had power of attorney over every one of the 30 retail trading accounts: Lee Chwan-hong – Fred Lee.

By the end of March, they had pieced together enough evidence to know they had a provable insider-trading case. It was time to start taking depositions from the lucky traders – which they would do in Hong Kong – and subpoena Wang, which they planned to do secretly in New York while Lee was being deposed in Hong Kong. The SEC lawyers had to decide who was going where. McGonigle, the supervisor on the case, had a scheduling conflict, so he would go to New York; Foster was happy to substitute for him in Hong Kong.

But Kaminsky and Beekman, laughing years later, recalled that in all their time working together, they had only one conflict: both really wanted to go to Hong Kong. They kidded each other about missing their first wedding anniversary, then flipped a coin. As it came down, Kaminsky caught it and slapped it on the back of his other hand. They peeked. He grimaced. Beekman was going to Hong Kong with Foster. He and McGonigle were going to New York.

[Lee] assured Perlis that all his trades were based on public information [...] Besides, Lee complained, he lost money on some of them. Who does that when they are trading on insider information?

Lee had received an inquiry from the SEC in May and needed a lawyer. He asked around and was soon in touch with Michael Perlis, a lawyer in the San Francisco office of Pettit & Martin. Perlis, a former assistant director of enforcement at the SEC – he had worked with Foster in the 70s – knew the drill. He questioned Lee about his trades. Lee had the air and aggrieved demeanour of a wealthy investor who had been wrongly accused. He assured Perlis that all his trades were based on public information – most were well-publicised deals, companies in play during the frenetic takeover boom of the time. Besides, Lee complained, he lost money on some of them. Who does that when they are trading on insider information?

Lee told Perlis he wanted to clear his name. He flew Perlis and an associate, Deborah Klar, to Hong Kong, first class, twice, first to go over his case, then to meet the SEC lawyers. He put them up at the Mandarin Oriental hotel, in Central. Wining and dining them around Hong Kong, he was wealthy and charming and wanted them to know it.

One day, he showed up with a pair of diamond and sapphire earrings for Klar. On the weekend, a Hong Kong friend took Perlis and some others on a yacht around Clear Water Bay. Though only 38, Lee seemed older, a fatherly type in a social stratum they understood only to be above theirs. To two Americans long before globalisation was part of the country’s daily vocabulary, he had a manner that may have allowed him more leeway in controlling a situation than they would have given to a Wall Street banker accused of insider trading.

Foster and Beekman arrived in Hong Kong a couple of days early to shake off the 12-hour time difference and prepare for the interviews. They stayed at The Harbourview, owned by the Chinese YMCA of Hong Kong, in Wan Chai. They ate local food. They took taxis. Their yachting experience was had on the Star Ferry. The contrast was apt. Lee, in nine months, had amassed illegal profits from insider trading equal to 20 per cent of the SEC’s annual budget.

They held no illusions that they would get straight answers to their questions during the depositions – crooked traders hardly ever admitted to their crimes, even under oath. The Grossman case had been won on circumstantial evidence about a single dirty trade. This one had two dozen dirty trades, but they still had to have depositions from the traders on the record, and there was no telling what might pop up during those.

On the morning of June 20, 1988, in a conference room at the US consulate, in Central, they began interviewing a procession of Taiwanese businessmen in whose accounts they believed Lee had placed the suspect trades. That Monday, with his lawyer on one side and translator on the other, each man sat across the table from Foster and Beekman. Foster asked most of the questions – “Do you know Fred Lee?” “Do you know Stephen Wang?” “Do you know …” naming, in succession, all the other men in the scheme. And so on.

Lee, despite having 19 million reasons not to be in a room under oath with SEC lawyers, wanted to anyway

The translator would translate each question. The men would converse in Chinese, sometimes for several minutes. Then the translator would look at Foster and Beekman. “He says, ‘No.’”

“Mr Lee’s name is right here on your brokerage account opening form. You’re sure you don’t know him?”

Again, the three men would converse in Chinese. “He’s sure.”

It went on like that for three days, none of Lee’s associates – one of whom may have been his own father – rolling over on him. The next morning, Thursday, they would move to Pettit & Martin’s office and start taking Lee’s deposition – Perlis didn’t want his guy being deposed at a US government facility.

As Foster and Beekman returned to their hotel that Wednesday evening, Wang was waking in New York. It was his 24th birthday. In Washington, McGonigle and Kaminsky were putting the final touches on the subpoena they planned to serve him the next day.

Perlis had been crystal clear with Lee – he was under no obligation to talk. But Lee, despite having 19 million reasons not to be in a room under oath with SEC lawyers, wanted to anyway. He was a smart guy, but it seems unlikely he understood the full possibilities of what might lie ahead. Even after becoming aware that the SEC was interested in him in May, he continued to trade on inside information. And he had left most of his profits in the US.

Businesswoman fined HK$24m for insider trading

Foster and Beekman spent Thursday questioning Lee, painstakingly asking him about trades and people. They suspected that he had not been truthful with his lawyers and they hoped that the questions they asked and the details they shared would expose this. Surely Perlis would never allow his client to lie under oath. The day went much like the three previous days, though Lee using a translator, despite holding American MBA and PhD degrees, added a farcical element to the process.

Meanwhile Kaminsky and McGonigle went to Morgan Stanley’s office in New York to serve a subpoena on Wang. After hours of sitting in a conference room and getting the runaround from the company’s lawyers – he’s not here; he’s at lunch; sorry, he left for the day – Kaminsky confronted one of them. Why were they messing them around?

A Morgan Stanley lawyer looked at him. “That’s what horse races are about.”

Kaminsky understood the cryptic message. Morgan Stanley had little to gain by putting a two-year analyst in a room with a couple of SEC lawyers. They weren’t going to help.

On Friday morning, the interview continued. Perlis had taken a hard line with the SEC all along, based on what Lee had told him, but his client hadn’t told him everything.

If Lee had spoken frequently with Wang, a guy he swore under oath he didn’t even know, how could [Perlis] believe anything else his client had said?

The investigators resumed questioning Lee; he resumed his effrontery. Perlis’ lawyer’s intuition began gnawing at him. The SEC lawyers’ questions were making him sceptical of Lee’s answers. Around mid-morning, Perlis excused himself, went to find a phone and called Morgan Stanley’s lawyers in New York. They told him that the SEC had been there hours before with a subpoena looking for Wang. Morgan Stanley’s lawyers had talked with Wang, who told them he knew Lee and spoke with him frequently, but denied tipping him. They shared some other details with Perlis.

Perlis was astonished. If Lee had spoken frequently with Wang, a guy he swore under oath he didn’t even know, how could he believe anything else his client had said? Worse, he, Klar and Lee’s Hong Kong lawyer had sat there for a day and a half while their client perjured himself. They may have been in Hong Kong, but they were all US-licensed lawyers sitting across from SEC attorneys while their client lied under oath. That’s not how it worked.

Perlis hid his agitation, returned to the room and suggested they break for lunch.

As he got up to leave, Foster left a chart on the table of the various connections Lee had with the others involved in the trades. It was a tactical move. Lee was connected to them all. It would be a good document for Perlis to study. But the lawyer didn’t need it.

Macau hacker in US extradition row ‘spent US$9 million on stock fraud’

When the SEC investigators were gone, Perlis looked at Lee. He told Lee that Morgan Stanley’s lawyers had just told him that Wang knew Lee quite well and that their phone records showed a lot of calls between the two.

Lee havered. The SEC lawyers had asked if he knew a “Stephen Wang”. He didn’t; he knew a “Steve Wang”.

Lee’s lawyers were nonplussed; his boat was sinking fast. Should they resign as his lawyers and get out? Or should they try to save him?

Perlis asked Lee to give them a few minutes alone. As he was making his way towards the door, Perlis stopped him. “Fred, don’t come back until you’re ready to tell us the truth.”

The three lawyers had just sat through a day and a half of Lee lying under oath to SEC investigators, found out about it and could not let it stand. It was a first for all of them, and they had to figure out what to do, fast.

When Lee came back into the room, they told him that his best option – really his only option – was to recant his entire testimony. He consented. Then he asked two questions. Did Hong Kong have an extradition treaty with the US? And would the SEC try to grab his money there? The answers were yes and yes. He left. Perlis and Klar never saw Lee again.

“Gary, sorry to call you in the middle of the night,” said Foster. “Fred Lee just admitted to insider trading – and Stephen Wang is the tipper”

When Foster and Beekman came back from lunch, boxes of uneaten food were on the table. Lee was gone. And his lawyers wanted to talk. Whether their discussion was on or off the record would be subject to dispute in the coming weeks. Foster would tell a US court that “the first thing I remember [Perlis] saying is that ‘[Lee’s] guilty’”. Perlis would claim that he was speaking off the record, on a hypothetical basis, trying to negotiate a settlement.

There would be no dispute about one statement Perlis made though: “Mr Lee has determined to withdraw his prior testimony given during these past two days and to advise the [SEC] staff that it cannot rely on the accuracy of the testimony provided by him in the investigation.”

It was an astounding turn of events.

Hong Kong was in a holiday mood by midday on Friday, preparing for the Dragon Boat festival that weekend. The two teams of lawyers hurriedly drafted a document to memorialise Lee’s recantation. Foster and Perlis made a couple of corrections by hand and initialled them. Then Foster and Beekman left. They had to find a fax machine.

Kaminsky’s phone woke him up at 1.30am in Washington.

“Gary, sorry to call you in the middle of the night,” said Foster. “Fred Lee just admitted to insider trading – and Stephen Wang is the tipper.”

Kaminsky was suddenly wide-awake. They were all aware that Lee knew Wang and were surprised that he had lied about even that. But to get him to admit he traded on Wang’s information – that was big. They talked for a while, Foster sharing some details of what just happened in Hong Kong. Then he told Kaminsky to track down McGonigle, who had stayed in New York, and give him the news.

When they hung up the phone, Kaminsky was pumped. This was his case, second in dollars only to Boesky. And they had nailed it. He put on Bruce Springsteen’s Thunder Road and poured himself a shot of vodka. The moment deserved a little celebration.

The moment didn’t last long, however. Minutes later, Foster called again. Before his seat in the conference room was cool, Lee was already trying to get his US$19 million out of the US. And, just like the Grossman case the year before, there would be nothing any of them could do about it once the money was gone. Kaminsky had work to do.

By 3am, Kaminsky was in the office with a team of SEC lawyers on the way. McGonigle was getting ready to take the first flight back to Washington. Kaminsky figured they had 14 hours – until 5pm on Friday – to stop Lee from getting his money out of the country. By the time the office opened, he was surrounded by senior SEC litigators.

Hong Kong insider trading activity down amid some rare buybacks

It soon became clear that there was no way they were going to be able to draft and serve the complex legal documents they needed to freeze Lee’s cash that quickly. Kaminsky and McGonigle started working the phones, calling the brokerages and banks. Their request was uncommon, but simple: “Look, we’re not asking you to not follow instructions from one of your clients. We’re just asking if you just might not get around to it today …”

The US brokerage houses and banks weren’t thrilled with either the request or the fact that it came only by phone, but they would play ball. “We can do this,” was their general response, Kaminsky recalled years later. “But you better be here Monday with a court order.”

The New York branch of London-based Standard Chartered Bank wasn’t so cooperative.

The SEC team worked through the weekend. At one point, McGonigle’s phone rang. It was his boss, Gary Lloyd, the assistant director of the branch. McGonigle told him they were moving as fast as possible, but the documents were very complex.

“Listen, if you’re still trying to get the docs perfect while Lee’s money is leaving the country, it’s not going to be a happy day.” McGonigle got the message.

The SEC’s complaint, filed in Federal Court on Monday, June 27, 1988, was front-page news in the US, Hong Kong and Taiwan

By Sunday night, Lloyd and the SEC’s national enforcement chief, Gary Lynch, were working alongside the others, drafting the documents needed to obtain a temporary restraining order to keep Lee from moving his money out of the country.

Midnight passed into the wee hours of Monday. Finally, McGonigle called out to the group: “Thirty minutes and we’re done writing!” They still had to have their admin staff, who were pulling all-nighters alongside them, finish typing and print everything.

At 6am, McGonigle, Kaminsky and others were on the shuttle to LaGuardia Airport, arranging papers and mapping out the fastest routes around Manhattan, first to the courthouse for a judge’s signature, then to serve the restraining orders on every brokerage or bank that might be moving Lee’s money.

The SEC’s complaint, filed in Federal Court on Monday, June 27, 1988, was front-page news in the US, Hong Kong and Taiwan. In September, Wang pleaded guilty to four felony counts, including one that dated to his first months at Morgan Stanley, when he tipped a childhood friend in return for US$4,000. He was sentenced to three years in federal prison, the same as Boesky, though his take-home, about US$200,000, was a bit less. Wang was released on parole in August 1989.

Perlis and Klar had been dealt a bad hand by their client and played it as well as any lawyer could. Pettit & Martin and Lee agreed to part ways and the two lawyers went on to distinguished careers in private practice.

Kaminsky, Beekman, Foster and McGonigle also enjoyed distinguished careers. Years later they remembered the case with the fondness and animation of a big success that attaches to one’s professional life and follows it down through the decades. Kaminsky, unintentionally highlighting why the good guys are respected for their public service, later recalled, with a laugh, his bonus for 1988: US$250.

Lee and Wang were two of about 50 Wall Street types caught up in the insider-trading crackdown of the 80s. Observers opined that the short prison sentences handed down at the time – a rarity for insider trading – would be effective deterrents against the crime in the future. Through the 90s and into the 2000s, insider-trading arrests were generally small news. But that didn’t mean it had stopped.

On March 1, 2007, that changed. The FBI charged 13 bankers, lawyers, hedge-fund employees and hangers-on that day – they were the first dominoes to fall in a round-up that ultimately saw more than 80 people convicted or plead guilty to insider trading and related felonies over the next seven years.

Hong Kong and London had similar crackdowns. The illegal profits some made dwarfed those of the 1980s, with single trades often netting tens of millions of dollars – one cleared US$270 million. Apparently a year or two in prison was not a compelling deterrent to a crooked but numerate gambler weighing those odds.

Sentences for the newly minted felons ranged up to 12 years, and maybe that changes the maths. As one who pleaded guilty said to me on a phone call from the prison in Alabama, where he was serving nine years, sentences of that length are “life altering”. He and his two partners started their scheme in 1994 and made about US$35 million before being arrested in 2011. One of the three, pressured by the FBI, ratted out the others.

It was a lot of fun and a lot of money, until it wasn’t.

Robert Boxwell is director of the consultancy Opera Advisors. He is writing a book on the US’ insider-trading scandals of the past decade, and another on China’s accession to the World Trade Organisation.