Domestic helper accuses former employer and convicted maid abuser of cruel campaign of injustice

Former civil servant, who threw scalding water over her Bangladeshi helper in 2014, kept a “punishment book” listing fines imposed on replacement maid for mistakes, including failing to marinade a cucumber and using the word “just”

Slumped dejectedly in her wheelchair and wearing a neck brace, former civil servant Au Wai-chun dissolves into tears and complains bitterly about the domestic helpers she says have turned her retirement into a nightmare. “Now I must bear the identity of a criminal until I die,” she says. “If I am unlucky enough to be convicted again, or if I die before the result comes, please promise to write an article that says a greedy maid can kill their ma’am.”

The 65-year-old says she believes her plight is the work of scheming helpers who have falsely accused her of abuse.

Hong Kong’s domestic workers share their stories of ‘living in’

“The judges are all on the maids’ side,” Au claims. “I am the victim [of] the judicial system and one tricky maid and one greedy maid. I want to alert other employers. Many people suffer from their maids.”

Begum Raksona was admitted to hospital with first- to second-degree burns, her trial was told. In her sentencing, District Court Judge Pang Chung-ping excoriated Au with the remark, “Not only did you destroy the trust foreign workers have in Hong Kong employers, but also their reputation.”

The former immigration officer defiantly continues to deny assaulting Raksona and has spent more than HK$3 million on legal fees to try to overturn the conviction and contest a compensation claim from her former helper, who was awarded HK$200,000 damages in a civil hearing.

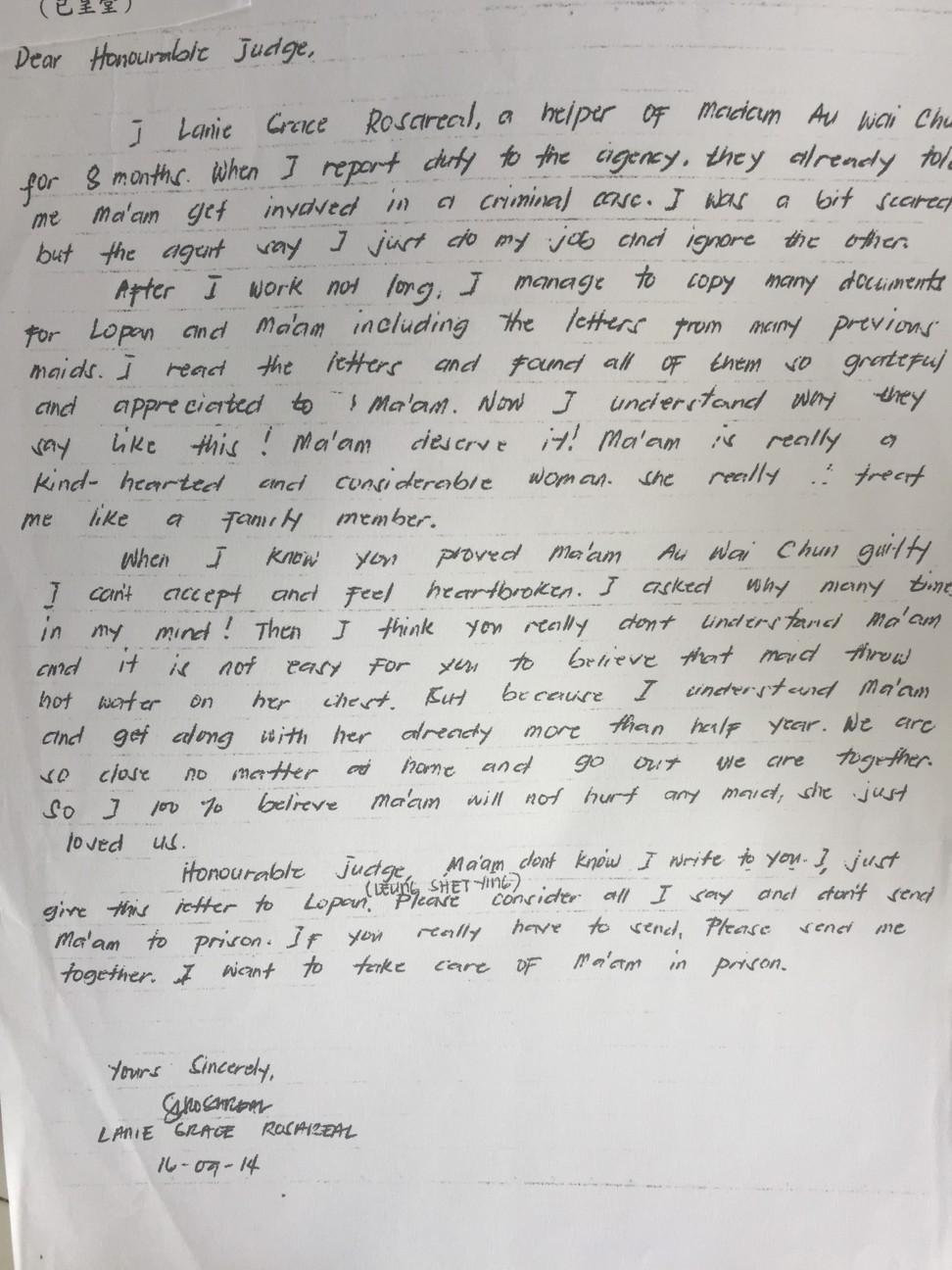

Au’s protestations of innocence have been further undermined, however, by a second complaint to the police – this time from the helper who replaced Raksona, and who pleaded with the judge not to jail Au at her 2014 sentencing. In a letter that may have helped spare her new employer a jail term, Lanie Grace Rosareal wrote, “I 100% believe ma’am will not hurt any maid. She just loved us [...] Please don’t send ma’am to prison. If you really have to send [her], please send me together. I want to take care of ma’am in prison.”

Having fled in November of last year what she claims was a cruel and protracted campaign of abuse and humiliation by Au, who she says told her to write the 2014 letter to the judge and dictated most of it to her, Rosareal is currently living in a domestic helpers’ shelter.

In a statement to police after she took flight from the residence in Tseung Kwan O that is shared by Au and fellow retired civil servant Leung Shet-ying, Rosareal says she feared for her life when Au allegedly held a pair of scissors to her throat and told her, “I want to get a chopping knife instead and chop you to death.”

The 28-year-old helper’s most remarkable item of evidence, however, is a notebook bearing the logo of the Hong Kong Companies Registry, where Leung worked before retirement. It was given to Rosareal by Leung and, in the six months before she fled, the helper was made to write down a daily list of her “mistakes”.

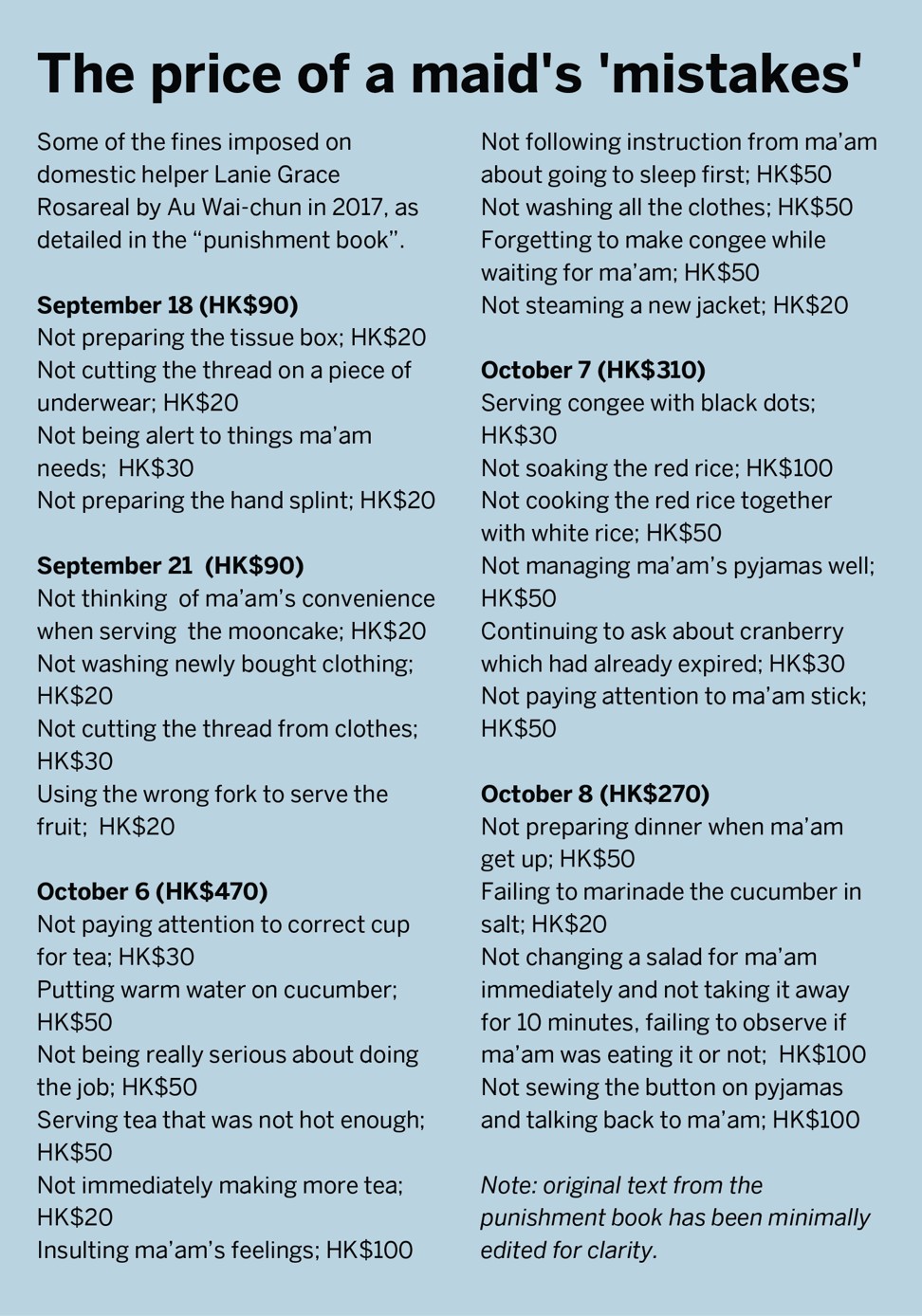

After Rosareal had written down her infractions, dictated to her by Au, the older woman would take a red pen and write fines for each offence in the ledger, which she called the “punishment book”, the helper claims, along with admonishments for the failings. The fines ranged from HK$10 to hundreds of dollars and those for one month alone – September 24 to October 24 – totalled HK$7,670.

At the end of each month, Leung (Rosareal’s registered employer) would hand the Filipino her wages of HK$4,210 then instruct her to hand the money directly to Au, to pay off the fines recorded in the punishment book, Rosareal alleges. The monthly total almost always exceeded her wages, so her “debt” would be recorded and carried forward, Rosareal says.

As a result, Rosareal claims, she received almost no wages at all for the last six months of her employment – receiving only between HK$200 and HK$350 for the rare months in which the fines were less than her wages. When she fled the flat in November, she “owed” Au a total of HK$3,750 in unpaid fines, according to the punishment book.

The fines were imposed for a bewildering array of misdemeanours: HK$100 for “disturbing ma’am when she [was] listening [to] the news”; HK$40 for arranging towels in a “poor butterfly shape”; HK$30 for putting too much water in Au’s tea; HK$20 for failing to marinade a cucumber in salt; HK$50 for not apologising immediately for a previous infraction; and – bizarrely – HK$30 for using the word “just” and HK$50 for using the word “misunderstood”.

On a single day in September last year, the punishment book recorded fines totalling HK$90: HK$20 for not preparing a tissue box; HK$30 for not being “alert [to] the things ma’am needs”; HK$20 for failing to prepare Au’s hand splint; and another HK$20 for failing to cut the thread on a piece of Au’s underwear.

On a day in August last year, Rosareal racked up a total of HK$140 in fines for falling asleep “when ma’am talking” (HK$50); serving a dish in an inconvenient manner (HK$20); not managing the bedsheets properly (HK$20); and “disturbing ma’am when watching [TV]” (HK$50).

At the end of every month, I knelt down and begged her not to take all my money [...] I asked her if I could have some money to send to my family but she answered that she wouldn’t give me a dollar, even if my family died. I went six months with almost no money at all

The pages include rebukes from Au such as “Nonsense maid!!” and “Performance and attitude crazy poor!!!”. On another page, Au writes in red pen: “Continue like this, I sure will send you to police! […] You so deserve!!!”

Speaking to Post Magazine, Rosareal says, “At the end of every month, I knelt down and begged her not to take all my money. But I only received insulting words from her. She told me I deserved to be punished because I made her suffer every time I made a mistake.

“I asked her if I could have some money to send to my family but she answered that she wouldn’t give me a dollar, even if my family died. I went six months with almost no money at all.”

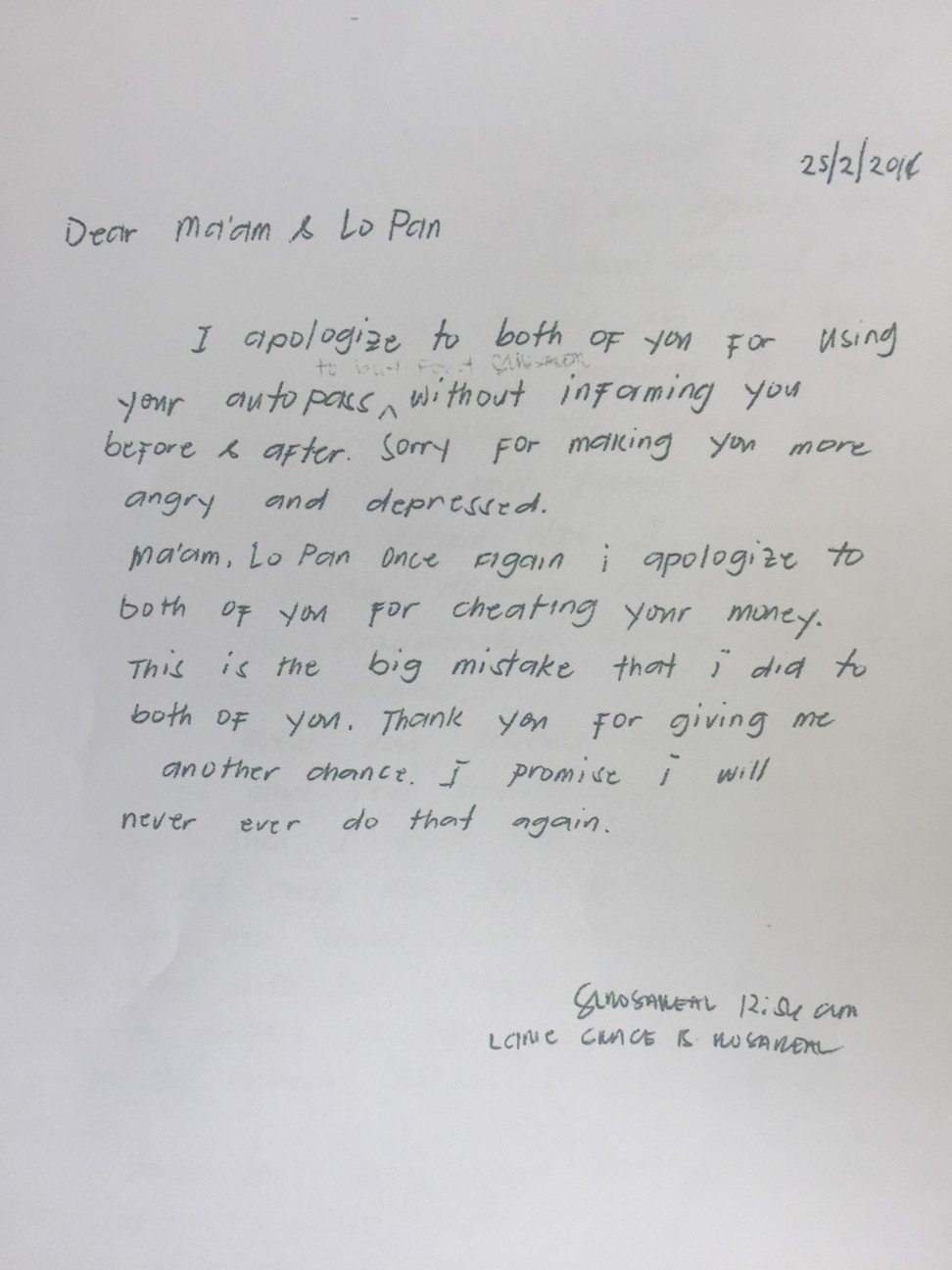

Rosareal – who says Au used her wheelchair only when she went out and was fully mobile without it when at home – says she put up with the punishment because she was in constant fear of being reported to the police for using an Octopus card belonging to Leung without permission in February 2014, soon after she had begun working for the pair.

“I was sent on an errand with an Octopus card owned by my employer. It was 4pm and I hadn’t had any lunch so I bought some bread for HK$28,” she says. “When I got back, I told them what I had done but, because of that, she made me write a letter that I used the Octopus card without asking for permission.

“From that time on, they used that to threaten me. They kept telling me the letter I wrote owning up to that mistake was valid for six years. Any time I didn’t do what I was told, they said they would call the police and show them that letter […] I was under their control and I couldn’t do anything.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, Au’s recollection of the event is strikingly at odds with that of Rosareal. Arriving in a hotel lobby near their home in a wheelchair pushed by Leung, she says she introduced the punishment book system to spare Rosareal from being fired by Leung when the helper’s performance at work was so bad her employer wanted to let her go.

“Sometimes [Rosareal] was like a naughty daughter,” says Au. “I used to work for the government but I was also a part-time teacher, so I just thought, ‘Imagine she is a naughty student.’ So I set up some rules for punishment, which could also have rewards.

“I said, ‘If one day you do not get a complaint from me, you can get a reward. If you do not do [a duty], we start with about HK$10 and if you repeat three times more, suppose maybe HK$20.’ I said, ‘You need money so, after you get the punishment, this will not happen again.’ This was my way.

“The punishment started with small sums. Sometimes she made many mistakes and did not write them down […] She continued to make many unforgivable mistakes. Her attitude was very proud.

“I had to set such a strict regulation because I didn’t want [these mistakes] to keep happening. She had a poor attitude and when I talked to her she did not look at me and did not answer. When Ms Leung saw her act like this, she said, ‘You are so impolite to ma’am. She treats you like a daughter […] You should respect her.”

Au insists that although she took the money from Rosareal to pay her fines from the punishment book, she often relented and returned it when the helper pleaded for it.

“The first time I said, ‘Don’t beg me,’” Au says. “Then she told me, ‘I don’t have enough to give money for the house [in the Philippines],’ or sometimes ‘for the baby of my sister’ or even ‘money to buy milk powder’ – all different reasons. After she says it like this, I give back the money.

“After several days or one week [following the payment of the fines], she would use my sympathetic character and give me many, many reasons – her mother is sick, or the baby is sick or her father cannot work, all the family is suffering from hunger. Then I would give the money back to her. In total, I didn’t get more than HK$1,000 or HK$2,000.”

There is no record – in the punishment book or anywhere else – of Au returning the fines she imposed, however.

“When I gave it back, I am so stupid; I didn’t write down that I gave it back,” she says.

Au emphatically denies assaulting either Raksona or Rosareal, saying her medical conditions – congenital heart disease and a degenerative spine condition – mean she is physically incapable of doing so. “Even if I could do it, I am not this type of human being,” she says.

Lanie says I shouted at her. But if you are facing a maid who is like a naughty girl every day – I suppose like a naughty daughter – would you not shout at her? But I would never shout for long because of the pain and the muscle stress [...] I had to stop and lie down

“Lanie says I shouted at her. But if you are facing a maid who is like a naughty girl every day – I suppose like a naughty daughter – would you not shout at her? But I would never shout for long because of the pain and the muscle stress [it causes]. It made me shiver with pain and I had to stop and lie down.”

Au believes her conviction was influenced by the high-profile case of Erwiana Sulistyaningsih in early 2014. Erwiana’s Hong Kong employer was jailed for six years in 2015, for beating the Indonesian helper over an eight-month period, in a case that sparked international outrage.

“The power of the maids’ association was very great. They always went in front of the court,” Au says. “I can’t believe this is Hong Kong. I have lived in Hong Kong all my life. It is known as a fair place with a fair judicial system but, after my case, I realised the judges are all on the maids’ side. Now I am a criminal. I can’t believe this has happened.

“I have already suffered enough from my pain and my disease. My spine problem will not let me die suddenly but with my heart disease I can die any time, suddenly. Now I just have to bear the identity of a criminal until I die.”

Au confirms she threatened to go to the police over the use of the Octopus card. “Though the amount is small, it is criminal behaviour,” Au says, but adds, “We cannot convince ourselves Lanie is really threatened [by this warning].”

More than eight months after she went to the police, Rosareal’s case is unresolved. Police have interviewed Au about the abuse allegations but no charges have been brought. The police said in an emailed statement that the investigation had been completed but was “pending legal advice”. Au has been told to report back to police at the end of the month.

The Labour Tribunal in January ruled Rosareal was entitled only to HK$2,408.70 in unpaid wages and travelling allowances for her final month of work. The tribunal told her she was not entitled to claim for the money handed over to Au under the punishment book system.

“That is nothing to do with the contract. You are being punished because maybe you have done something wrong and that’s why the employer punish you or that Madam Au punish you and you have to pay compensation to them,” Rosareal was told by deputy presiding officer Mary Wu Chau Yuen-man, who advised the Filipino to go to the Small Claims Tribunal, according to a transcript of the hearing.

Rosareal’s case has been closely followed by Daisy Mandap, editor of The Sun newspaper for Filipinos in Hong Kong. Mandap says the case is one of the worst she has encountered.

Systemic abuse of Hong Kong domestic helpers, and how to stop it

“She was held a virtual prisoner and made to feel she actually deserved the punishments she was given,” Mandap says. “For someone who is well educated and gregarious to be in a situation where she is reduced to thinking she deserved being punished in that way is shocking. The police should take this seriously because Au has a previous record. I don’t know why it is taking them so long.”

Patricia Ho, a human rights lawyer with Daly, Ho & Associates, who is representing Rosareal, says her case highlights the need for an overhaul of employment rules for helpers in Hong Kong.

“When employers are able to exercise such physical and mental control over domestic helpers, the employment structure of domestic helpers should certainly be put into question,” says Ho. “This includes how the live-in rule heightens the risk of abuse and threats to personal security.

“This case paints a picture of potential forced labour, highlighting the concern that forced labour is not a crime in Hong Kong, and that the law fails to serve as a deterrent to abusive employers.”

Nine months after fleeing Au’s home, Rosareal says she has slowly come to terms with what she experienced, helped by regular counselling sessions since she entered the Bethune House Migrant Women’s Refuge.

“Au would make me kneel down facing the wall for an hour for punishment, sometimes,” she says. “When I first left, I was still scared of her. Now I am just angry.”