‘Medical Marco Polo’: the American doctor who fought for lives of Chinese amid chaos of civil war

Dr Leo Eloesser turned his back on success in the United States to follow humanitarian dreams on the other side of the world

We share an umbrella as we walk the hilly streets of San Francisco on a drizzly day. It is not ideal weather in which to search for an outdoor statue, and we find to our surprise – on arriving at the correct spot – that a building stands there, with two majestic columns of granite, carved with giant human figures, reaching towards the sky. Today the building is a fitness centre; it was once the Pacific Coast Stock Exchange.

But what of the statue? Is this the right place? How could the statue of a man who so passionately advocated socialised medicine stand in so high a temple of capitalism?

Behind one of the columns, hidden by overgrown shrubbery, we find it: the rendering of a short man peering through a microscope. It commemorates Dr Leo Eloesser, a humanitarian whose bond with China spanned decades.

Along with the better-known Norman Bethune, Eloesser was one of 21 foreign doctors who volunteered to work in China having served on the Republican side in the Spanish civil war (1936-39).

A large collection of documents concerning Eloesser – some 50 boxes in all – has been preserved in the Hoover Institution Library and Archives, at Stanford University, in the United States, where he served as a professor for 34 years. Among them are his memoirs, correspondence, lecture notes, medical drawings, reports, news clippings and photographs. Together they reveal an extraordinary life.

Eloesser was born in San Francisco on July 29, 1881. After graduating from Heidelberg University, in Germany, he returned home to work at the San Francisco General Hospital and run his own clinic. Barely five feet tall, Eloesser often stood on a stool to perform surgery. Nevertheless, his acumen for diagnosis and daring in performing risky operations led Stanford to award him a professorship at the age of 31.

He was also something of a pioneer. A surgical procedure known as the Eloesser flap – which aided drainage of tuberculous empyemas at a time when there was no effective medication to treat tuberculosis – is named after him. And his clinic was affordable for all: the poor and hospital workers did not pay for treatment; others were expected to contribute according to their means.

It was 12 days before Eloesser’s 55th birthday when the Spanish civil war erupted, in 1936. Left-leaning loyalists were fighting against rightists headed by General Francisco Franco and aided militarily by Nazi Germany and fascist Italy. The reports of destruction and suffering were shocking and, in September 1937, Eloesser made a decision.

“I want to help the loyalist cause and the best way that I see to do so is to offer my services to the stricken in Spain,” he told the San Francisco Chronicle newspaper.

Raising US$50,000 in private donations to finance an ambulance and hospital unit, Eloesser organised a volunteer group of Pacific coast medical professionals to go with him to Spain. He presided over a meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, of which he was president, before leaving for Europe, ahead of his team, in November 1937.

Eloesser may have been older than most of the 40,000 or so volunteers from 53 countries fighting for the Republicans in Spain, but he rivalled those younger with his energy and skills, setting up mobile field hospitals and serving on battlefields for nine months.

I was on the blacklist; ‘Premature Anti-Fascist’ it was called. I’d been in Spain. Anyone who had been in Spain was a Communist.”

When American troops entered Europe during the second world war, Eloesser offered his hard-won expertise working in a war zone, but “the United States would have none of me”, he recalled in his memoir, Medical Service to the Chinese People: Its Beginnings and its Development. Notes of a Medical Marco Polo, a book that was never published but that is now held in the archive at Stanford. “I was on the blacklist; ‘Premature Anti-Fascist’ it was called. I’d been in Spain. Anyone who had been in Spain was a Communist.”

So Eloesser continued to work in San Francisco, his colleagues returning to the US when Germany surrendered in May 1945. On the other side of the Pacific, however, China was still riven by conflict.

Signed up as a surgery specialist with the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), Eloesser left New York on July 28, 1945. By the time he reached China, in August, Japan had surrendered.

Fighting, however, would continue to rage, with the Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek and the Communist forces of Mao Zedong battling for control of the country. Eloesser initially stayed in Chungking (now Chongqing), then the Nationalists’ wartime capital, in the southwest of China, soon heading up a UNRRA teaching programme in nearby Geleshan.

In the spring of 1946, however, while visiting Peking, Eloesser received an invitation from George Hatem, an American doctor who had settled in China years earlier. They flew together to Kalgan (modern-day Zhangjiakou, in Hebei province) and then to Yanan, in Shaanxi, for a tour. Known as the “Red Capital”, Yanan was the city from which Mao ran the Communist military campaign, and Eloesser visited the Bethune International Peace Hospital there, named after his old friend from Spain.

Bethune, a Canadian, had come to China in January 1938, aged 47. He volunteered to work on the front, trained soldiers as medics and established medical schools. While operating on a wounded soldier, he was infected through a cut and died of septicaemia in northern China in November 1939. An article written by Eloesser about Bethune for The Journal of Thoracic Surgery in April 1940 concluded, “What better end could any man have than this fellow member of ours, who spent his life and met his death in the service of his ideals – Humanity and Freedom.”

The Bethune International Peace Hospital today stands in the city of Shijiazhuang, in Hebei province, but Eloesser’s visit was to a facility in Yanan that, he noted in his memoir, occupied two dozen caves, primitive but clean. “The nurses had no watches, but counted the pulse with a 30-second sandglass. Hemostats, forceps, retractors and a fracture apparatus were forged from old steel rails in the arsenal.”

The Chinese volunteers who fought in the Spanish civil war

In a 1946 report to the UNRRA, he wrote, “The bleak figures and phrases of an official report fail to portray the youth, hope and vigour that inform the efforts of the people of the Communist areas; their efforts to better their health are but a part, probably a minor one, of their vast ambitions. Their ideas cannot but arouse interest.”

By the time he left Yanan, the doctor’s thoughts had crystallised. “The excursions to Kalgan and Yan’an let light into me of what I might do and how I might be useful,” he wrote in Medical Service to the Chinese People. “For it was apparent to me, if not to my Chinese students and colleagues in Nationalist China, that thoracic surgery had little to do with the welfare of Chinese villagers but that teaching like that I had seen in Yan’an might help them.”

In February 1947, Eloesser flew back to the US for three months. News media sought out his thoughts on the situation in China, and he used the word “chaos” to describe the Nationalist government’s handling of materials sent over by UNRRA. “Supplies are left on docks and stored in warehouses,” he told the San Francisco Chronicle. “There are mountains of them. I saw 12,500 tons of medical supplies in Shanghai which were not being distributed.”

He observed that “one can buy from Chinese peddlers United States foods which could have come to China only through official channels”.

And he argued that poor sanitation, dirty water and diseases caused by insect bites were the country’s biggest killers. “Millions of Chinese could be saved,” he said, “if we could but introduce teachings of simple things like boiling water, cleanliness and a decent sewerage system.”

Eloesser returned to China in May 1947, to join the World Health Organisation (WHO) in Shanghai. Within a year he was assigned to a Communist-controlled area in northern China. His team included nurse Ruth Ingram, who had been born in Peking (Beijing) to American medical missionary parents and spoke the local dialect, and a young Chinese surgeon whom he referred to in his writings only as Dr Li, and who could also help with translation.

During December 1947, the trio sat forlorn in a hotel room in Tianjin, 120km southeast of Beijing on the edge of Communist territory. For a fortnight they had been unable to obtain a military pass to enter the area. On December 21, a long UNRRA convoy stood before the hotel, but without passes, Eloesser, Ingram and Li could not leave with it.

Official accounts of Nationalists’ role in fight against Japan now seen more positively

Eloesser approached Perry Hansen, the leader of the convoy, sitting in a jeep. He recalls the conversation in Medical Service to the Chinese People. “Don’t you want a few morphine tablets to take with you, Perry?” Eloesser asked. “There might be a little shooting in No-Man’s Land and a few tablets might come in handy.”

“Okay,” said Perry.

Eloesser went to his room to retrieve the tablets. On his way back with the morphine, a sudden hope rose.

“Don’t you want a doctor to go with you, Perry? You might need one.”

“Okay. Hop aboard the weapons carrier.”

Eloesser jumped in and the convoy rumbled away, leaving him no time to inform Ingram. With no overcoat, he wrapped himself in a blanket against the winter cold. When later a convoy truck became stuck on a river bank, and the weapons carrier was sent back to Tianjin for help, it took with it a note from Eloesser to Ingram: “Go aboard tomorrow and bring as much duffle with you as you conveniently can,” it read. “Also my surgical kit and paper and passport and money and a few shaving things and clothes, for I haven’t a thing with me.”

The Chinese soldiers who fought in the American civil war

Ingram and Li caught up with Eloesser on Christmas Day and the trio travelled on to the village of Shilidian, in Hebei province, as far as they could go by road. The chairman of the Communist regional government there suggested their services would be best put to use at another hospital named after Bethune, this one in Xijing, Shanxi province.

Eloesser, Ingram and Li rode the final 25km westward to Xijing – an ancient village in the Taihang Mountains – on horseback in the face of a freezing winter dust storm (which the nurse paid for with a bout of pneumonia that laid her low for a fortnight). There, they were greeted with paper banners of welcome, hospital staff and patients crowding the cobbled streets to shower them with speeches and songs, and received by Dr He Mu, director of the hospital. Born in Shanghai, the 43-year-old had been trained at the University of Toulouse, in France, and spoke fluent French. He requested that Eloesser train staff in emergency surgery and Ingram in communicable diseases. Li would translate their typed notes for students to copy by hand.

Their teaching style was modelled on that of Bethune, primarily using demonstrations, with students – who lacked theoretical knowledge of medicine – learning through imitation and rote. Later, on October 31, 1948, Eloesser’s methods would be reported in the New York Herald Tribune: “The W.H.O. representative demonstrated treatment of chest injuries with a chicken, and had his students practice intestinal suture and repair of internal injuries on the body of a pig.”

Without access to mail or telephone, Eloesser had no distractions during his 3½ months in Xijing, his days filled with teaching, occasionally performing surgery, studying Chinese, playing the viola and taking lessons on the two-stringed Chinese fiddle. Water had to be carried up to this mountain village, and he had also to learn to bathe under a puny trickle running from a can with a hole punched in its side.

Like local peasants, Eloesser wore a quilted cotton uniform, but he slept at night on a camp cot in a room warmed by a coal-fuelled stove. Villagers affectionately called him lao dai fu, which essentially means respected doctor.

Eloesser and Ingram left Xijing, leaving Li behind, again on horseback, on April 25, 1948, the entire hospital staff and a good complement of villagers gathering to wish them a safe journey. Eloesser was heading for Shijiazhuang, where he met Dr Su Jingguan, chief medical commissioner and head of the army medical service there. Su was tall, spoke little and listened patiently and attentively. The American wrote in his memoir, “I never knew a man with broader vision and clearer insight, not one, who with his countless duties, was more capable of assimilating detail.”

Having now worked in China for almost three years, Eloesser’s ideas had evolved.

“It seemed to me that importing expensively equipped hospitals and specialists, and sending young Chinese doctors to specialize in foreign hospitals were not likely to help the health of the Chinese people,” he wrote. “What was needed were many persons to carry out simple preventive measures – to vaccinate and immunize against smallpox, typhoid, cholera, diphtheria; to teach simple hygiene […] to assist in childbirth and teach infant care.”

Health is the right of everyone, and not the privilege of a favoured few. Health of the people can be achieved [...] by ordinary means within the grasp of everyman; by killing flies and lice, by properly disposing sewage, by cleanliness and decent living

Eloesser added that “it might be possible and not too difficult or time-consuming to do these things”.

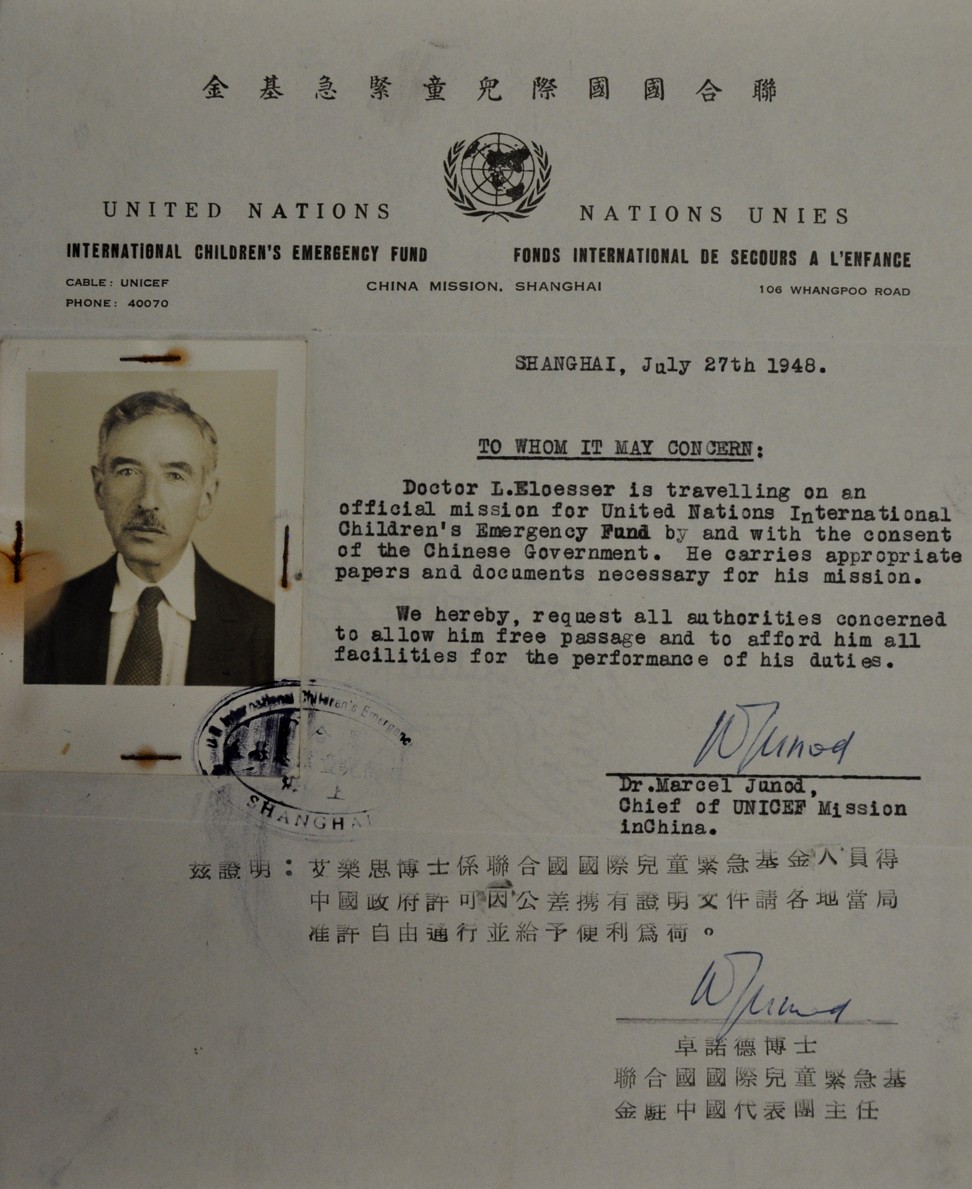

The American shared these ideas with Su, and when, a few months later, he was sought out by Dr Marcel Junod, the Swiss-born chief of Unicef’s China mission, who wanted advice on how best to spend US$500,000 of funding in northern China, Eloesser suggested an appropriate medical training programme. Junod agreed and asked the WHO to release Eloesser to head up the new project.

The Unicef training school was to be built in a former Trappist Ben-Du monastery, where an anti-epidemic bureau had been established, near Shijiazhuang. The bureau’s head was Dr Li Zhizhong, a graduate of Aurora University, a French Jesuit college in Shanghai. The new school would teach midwifery, communicable diseases, sanitation and first aid, and on November 22, 1948, the People’s Health Workers Training Course began with 20 students in attendance.

Eloesser gave an introductory address at the inauguration, which is recorded in a WHO newsletter from the period. “Health is the right of everyone, and not the privilege of a favoured few,” he said. “Health of the people can be achieved. Achieved not by complicated and costly methods of surgical operations done in the ivory towers of electrically equipped and air-conditioned operating rooms, but by ordinary means within the grasp of everyman; by killing flies and lice, by properly disposing sewage, by cleanliness and decent living.”

Eloesser’s approach, similar to that of Bethune, was to teach his students simple procedures that could be carried out precisely. He encouraged them to use materials at hand. Students fashioned tweezers from bamboo and wire, splints were made from local gypsum and cotton bandages were woven locally by hand.

When the first training course at the monastery concluded in mid-February 1949, Eloesser moved to Peking to prepare for a second in nearby Tongzhou (which today is a district of the capital). Eighty more students were trained beginning in July 1949 and the two courses served as a model for the training of millions of future barefoot doctors.

After Unicef withdrew from China – following the UN’s refusal to recognise the new People’s Republic – Eloesser reluctantly returned to the US in October 1949. He was soon assigned to the organisation’s headquarters in New York as medical adviser. A year later, at the height of US senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-communist witch-hunts, he was called before a congressional investigative committee. “I was not and never had been a communist or a party member,” the doctor testified.

Were I permitted to return, I’d be glad to spend the rest of my days in China

The prosecutor asked whether he had known any communists. Eloesser replied that he had, naming dead party members as well as Zhou Enlai, premier of the People’s Republic of China. Eloesser was dismissed, but he knew his reputation would be forever tainted by the choices he had made. He expressed his misgivings to author and fellow doctor Harris Shumacker, who recorded them in the biography Leo Eloesser, M.D.: Eulogy for a Free Spirit (1982): “My black past, especially my service in Spain, I suppose, has effectively barred me from government service of any kind.”

Following his 70th birthday, in 1951, Eloesser resigned from the UN and left the US with his companion, Joyce Campbell, for Mexico. They eventually settled in Tacámbaro in 1953, where they built a ranch. Each morning, Eloesser would hold a free clinic there for nearby peasants, prompting the US Internal Revenue Service to inquire about his income from the practice. He responded that all the services he offered were free of charge or paid for in manure. If that was considered income, he would gladly pay for the assessment.

In Mexico, Eloesser devised basic medical programmes for the poor in Latin America, based on his experiences in China. He also revised the teaching text he had written in China and, in 1953, published it as a manual titled Assembly Line for Country Midwives. But Eloesser longed for China. Frequently, he wrote in his memoir, he would wake up in the middle of the night, exclaiming, “I wish I were in China this very minute!” Each night he would spend an hour practising writing and reading Chinese. “Were I permitted to return,” he wrote, “I’d be glad to spend the rest of my days in China.”

Eloesser’s dream of returning was finally realised in the autumn of 1973, when he was invited to Beijing as a member of a Mexican medical delegation. Having left China 24 years earlier, Eloesser, now aged 92, was warmly greeted by his old friend Hatem and reunited with Dr Li Zhizhong, with whom he had worked at the Ben-Du monastery. And when a short Chinese man with a sparse beard arrived, Eloesser flew into his embrace. It was Dr He, who had headed the hospital in Xijing, where Eloesser had worked in 1948.

While in Beijing, Eloesser claimed in his memoir, he witnessed surgery performed under anaesthesia by acupuncture. Had he not seen it himself, he wrote, he would not have believed it possible. He was impressed too by the system of barefoot doctors that was now in place, telling one friend, “The rapidly trained medical personnel, carries essential and preventive medicine to the farthest corners of the countryside.”

On October 4, 1976, while on his way to seek medical treatment in the Mexican city of Morelia, Eloesser collapsed and died from a coronary occlusion. He was 95. He had been feeling unwell on the day before he died, but remained at his clinic treating patients.

In the years before his passing, Eloesser had set up a substantial trust account with the Banco Nacional de México “to be divided into loan fund accounts for needy students of medicine in Central and South America”. In his will, he stated, “I request and beseech that my name not be used to wheedle contributions from my friends or anyone else for any institution or cause, educational, political, charitable, artistic, or any other whatsoever,” effectively preventing those who knew him at Stanford from establishing a surgical professorship in his name.

Eloesser had rather grandly coined the term “Medical Marco Polo” for himself, which was recorded in the San Francisco Chronicle as early as 1949, but in Shumacker’s biography, he explained how he differed from the 13th-century Venetian merchant, whose writings first described to Europeans the great wealth enjoyed by China’s rulers.

“Marco Polo, after his eighteen years’ sojourn in China, is said to have remarked that he went to teach, but remained to learn,” Eloesser said. “I, too, embarked for China to teach and remained to learn, but, unlike my illustrious predecessor, gathered my teachers and learned my lessons not at the court of Khans, but at ever lower and lower levels.”