Yemen refugees’ arrival in Jeju splits South Korean resort island

Arrivals from the Middle East have sparked a debate about the country’s role in accepting asylum seekers

Hamza al-Odaini had two paths before him after he graduated from secondary school in Yemen: be forced to pick up a gun and fight in the civil war, now in its fourth year, or flee the country. In the end, his mother decided for him, sending the 17-year-old on a journey through Oman and Malaysia, before he landed on the South Korean resort island of Jeju. He hoped to study to become an engineer, but in the two months since he arrived, there has been a rude awakening.

“It was really hard to leave, but it’s better than staying and being captured and forced to fight,” Odaini says. “When I had to accept I am going to be a refugee, I thought that meant I would have a better life, I’ll be able to go to university and I’ll get financial support. But this is totally different than what I thought.”

The arrival of Odaini and more than 550 other Yemeni refugees has sparked intense debate in South Korea over the country’s role in accepting asylum seekers, with the population split between calls for compassion and immediate expulsion. Much of the anti-refugee rhetoric has taken on Islamophobic overtones, and detractors point to the European refugee crisis as a lesson of the woes of unchecked migration.

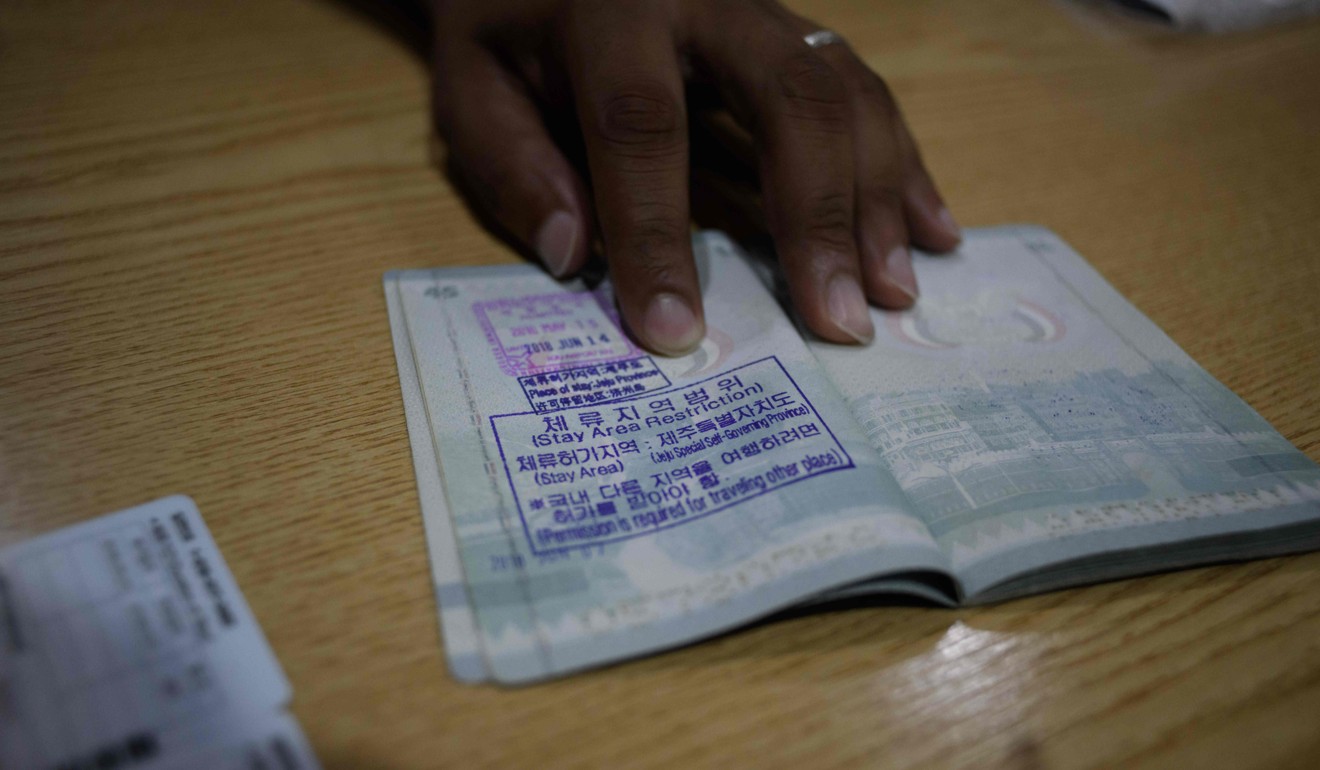

Amid the influx of asylum seekers, in June the government removed Yemen from the list of countries allowed visa-free access to Jeju. Immigration authorities have barred the refugees from travelling to mainland South Korea, and while they are allowed to work, employment has been restricted to fishing, fish farms and restaurant work. Many remain unemployed.

While most of the Yemenis who arrived are single men, Jamal Al-Nasiri made the trip with his wife and five daughters. They have been taken in by a family, and while the children are unable to enrol in school, local volunteers come to the house to teach them Korean.

“I want to learn from these people how to make a good life, how they built a modern industrial country. There was a war here in Korea before, but after they built themselves a rich society,” Nasiri says. “I just want to make things better for my country, but we’re still in the war for a long time and I must protect my family.”

Meanwhile, more than 630,000 people have signed a petition calling on the South Korean government to revoke the Yemenis’ refugee applications and have them expelled from the island. The presidential office typically responds to petitions that garner more than 200,000 signatures, but so far President Moon Jae-in, himself the son of refugees from North Korea, has stayed silent on the issue.

While there was a trickle of refugee applications in South Korea for years, more than 10,000 people applied for asylum last year, with only 1.2 per cent, or 121 cases, accepted, according to the justice ministry.

I am absolutely against having refugees. I really hate the thought of people with the religion of Islam living on Jeju in a large number

Those numbers do not include the more than 30,000 North Korean refugees living in South Korea, whose presence has been largely accepted and who are given citizenship and government benefits upon arrival. They are welcomed amid a mantra that South Korea is racially pure – a danil minjok or mono-ethnic nation – and this idea was part of the official school curriculum until the UN advised it should be removed in 2007.

Hundreds protested in Seoul against accepting the Yemenis, calling them “fake refugees” and accusing them of being economic migrants. Online forums for mothers on Jeju, which usually host stroller reviews or discuss the best kindergartens, have turned political in recent months.

“I am absolutely against having refugees,” one woman wrote. “I really hate the thought of people with the religion of Islam living on Jeju in a large number.”

Others point to the refugee crisis in Europe, and hope to avoid a similar fate for South Korea.

“I used to live in Europe ... and accepting the Muslim population is literally a crazy idea,” wrote another.

Despite the animosity, people on Jeju have been largely kind to the Yemenis in their midst, with hotel owners giving discounted rates and people donating food, blankets and clothes.

“They fled for survival and they’re here looking for a better life, so we should take them in,” says Son Chun-ja, a merchant selling fermented soybean sauces and pickled vegetables at the island’s largest market. “It’s the same for Koreans who fled in the past, looking for a better life, it would be horrible if those Koreans were kicked out.”

For now, the migrants are simply trying to keep themselves busy and begin the process of rebuilding their lives.

Odaini worked on a fishing boat repairing nets for three days, his first job, before his boss discovered his age and fired him. He now spends his days like many Yemenis on Jeju, studying Korean and talking with friends.

As one of the younger refugees, he has been taken in by a Korean family, members of the local Catholic Church. But thinking of his mother still brings him to tears.

“The last time I saw her, she told me to live peacefully,” Odaini says. “She told me to take care of myself and study hard.”

The Guardian. Additional reporting by Youngjoo Kaitlin Kang