The greatest job in the world: US policy adviser recalls working with Jacques Cousteau

Paula DiPerna, the New York-based writer and speaker who worked with the legendary explorer for 20 years, says he was “an amazing person, very open-minded, child-like”

Making the world your oyster I was born in New York City, in an Italian enclave. I went to public schools, it was a real melting pot – there were black children, Puerto Rican children. I was in a big hurry to get through my education, the only thing I really wanted to do was write.

I did my undergraduate and graduate degrees in comparative literature. I applied for a fellowship to do a doctorate in comparative literature, but didn’t get it. It was my first big rejection. I decided instead to become a public school teacher and taught in East Harlem.

Then the fiscal crisis hit – in the mid-1970s New York City was totally bankrupt – and a lot of young, idealistic, committed young teachers were laid off. I was taking an evening class at university with Victor Navasky, who was editor of The Nation. I told him I’d been laid off and what was happening with the city schools and said I thought it was a story. He agreed and I pitched it to The Village Voice. The editor read the story and said, “Great story, bad execution.” That was my second big rejection.

I took a walk, thought he was right about my story, it was boring, and restructured the lead. He published it and I earned my first professional journalism money – US$150 – and I haven’t looked back since. What I learned from all this is that the world is not your oyster – you have to make it your oyster.

Joining Jacques I started freelancing, writing about the public school system. A friend gave me a membership to the Cousteau Society as a Christmas present – it came with a newsletter that said the society was looking for volunteer writers and editors to work on a book project. I called them up and went for an interview. By this time I had written a book (The Complete Travel Guide to Cuba [1979]) – the first travel guide to Cuba for English speakers since the revolution. The editor offered me a full-time job as a writer on a project called The Cousteau Almanac (1981).

It was probably one of the 10 greatest jobs in the world at the time – and a big part of that was because [Jacques Cousteau] was such an amazing person, very open-minded, child-like

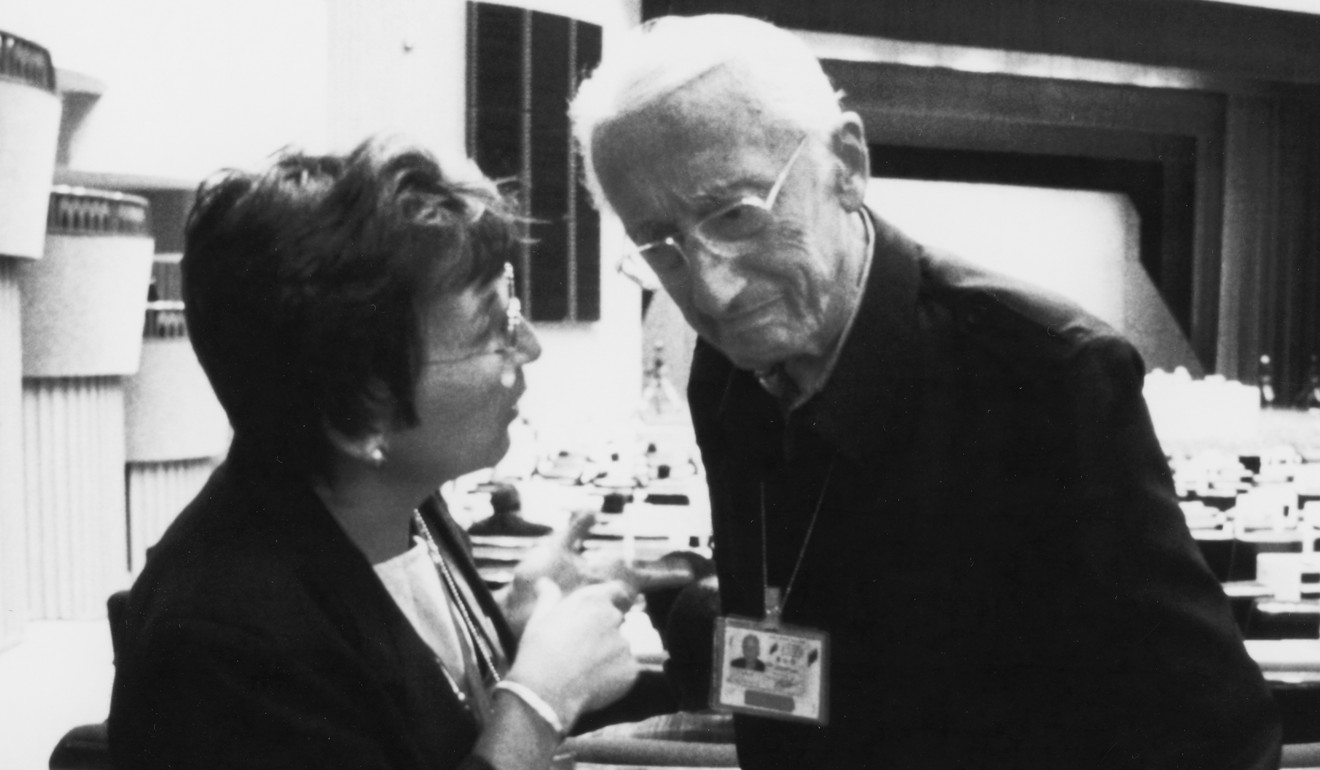

During that time I got very close to (marine explorer and documentary maker) Jacques Cousteau and became a film writer. I went on to work with Cousteau for 20 years – from the late 70s to the late 90s – and became (the Cousteau Society’s) vice-president for international affairs.

For 20 years I travelled all over the world – I was in Paris many times, we had an editing room in Los Angeles, I was on expeditions almost all the time, I spent a year in the Amazon, Cuba, Haiti, New Zealand, Australia, just about everywhere. It was probably one of the 10 greatest jobs in the world at the time – and a big part of that was because he was such an amazing person, very open-minded, child-like.

Saving the Antarctic There was no one in the world who didn’t want to meet him, we had access to every head of state and we accomplished a couple of great things. In 1986, at the height of the most difficult relations between the US and Cuba, we got 50 political prisoners out of Cuba. I was the engineer of that.

Aside from the films and travel, which were life transforming, the other thing I’m proud of with Cousteau was, in 1991, when we helped secure a 50-year moratorium on mineral and oil exploration in Antarctica called the Madrid Protocol.

I was on a plane with Cousteau and he was reading the International Herald Tribune and tore out the back page and handed me the item, which said “the Wellington Convention is about to be ratified by the nations who were party to the Antarctic Treaty and this will permit mineral and oil exploration in Antarctica”. He told me, “Paula, we can’t let this happen.” He had access to (French president François) Mitterrand and (US president George H.W.) Bush and we managed to get rid of the Wellington Convention.

There was no one in the world who didn’t want to meet [Cousteau], we had access to every head of state and we accomplished a couple of great things

What price the environment? Cousteau was aware that if there was a lot of oil and mineral wealth in Antarctica, it couldn’t be smart to go after it at a time when the world didn’t need it and the prices would be very low relative to the price when the world did need it. He was essentially saying the oil is worth more in the ground than it is being burned right now.

It was the beginning of the awakening of this idea of environmental finance – that there is an invisible price to using up resources too cheaply. His genius was to be ahead of the curve. What I got out of that was that the environment has a financial value and getting things done requires deliberation, incisiveness and following details.

How to spend a billion dollars In the late 90s, I was in my late 40s and decided to leave the Cousteau Society and have a sabbatical. I’m a golf nut so I wrote a book about golf. I heard there was a search on for the head of a philanthropy foundation in Chicago called the Joyce Foundation. I sent in my CV and ended up getting the position.

The foundation had US$1 billion and we gave away US$50 million a year. I worked there for several years and would have stayed longer, but 9/11 occurred. I’m a dyed-in the-wool New Yorker, all my friends and family are in New York, and I knew the world would never be the same again. I resigned and went back to New York, where I got involved reviewing recovery grants for 9/11.

I came to China with Richard and, in 2008, we did a joint venture called the Tianjin Climate Exchange. I was deeply ensconced in the private sector and markets and the idea of how you price these intangibles. I became involved with the Carbon Disclosure Project and now I talk and write about environmental finance.

I have no pets, no plants, no children – independence is my biggest asset and I’ve always felt I should use it

Hong Kong and a state of independence My time is taken up with trying to get a breakthrough on climate change. I was invited to come to Hong Kong to spend time with the Civic Exchange, because they are focused on the role of Hong Kong as a hub for green finance. Hong Kong has observed that there’s a role for it in this emerging field. Mainland China has also identified green finance as a key area.

I’m here to help Civic Exchange think about what policies Hong Kong might introduce to help it capitalise on its financial-services reputation and also integrate with regional ideas. I’ve learned that if you want to take advantage of all these opportunities in life you have to be a generalist. The other thing is I have no pets, no plants, no children – independence is my biggest asset and I’ve always felt I should use it.