Growing up in 1930s Shanghai: Hongkonger’s memoir of soirees, school days, a shooting and some Black Swans

Isabel Chao’s 2008 visit to her childhood home sparked an idea for a memoir on life in pre-Communist Shanghai. Chao, who co-wrote the book with her daughter, explains why she decided not to focus on the tragic

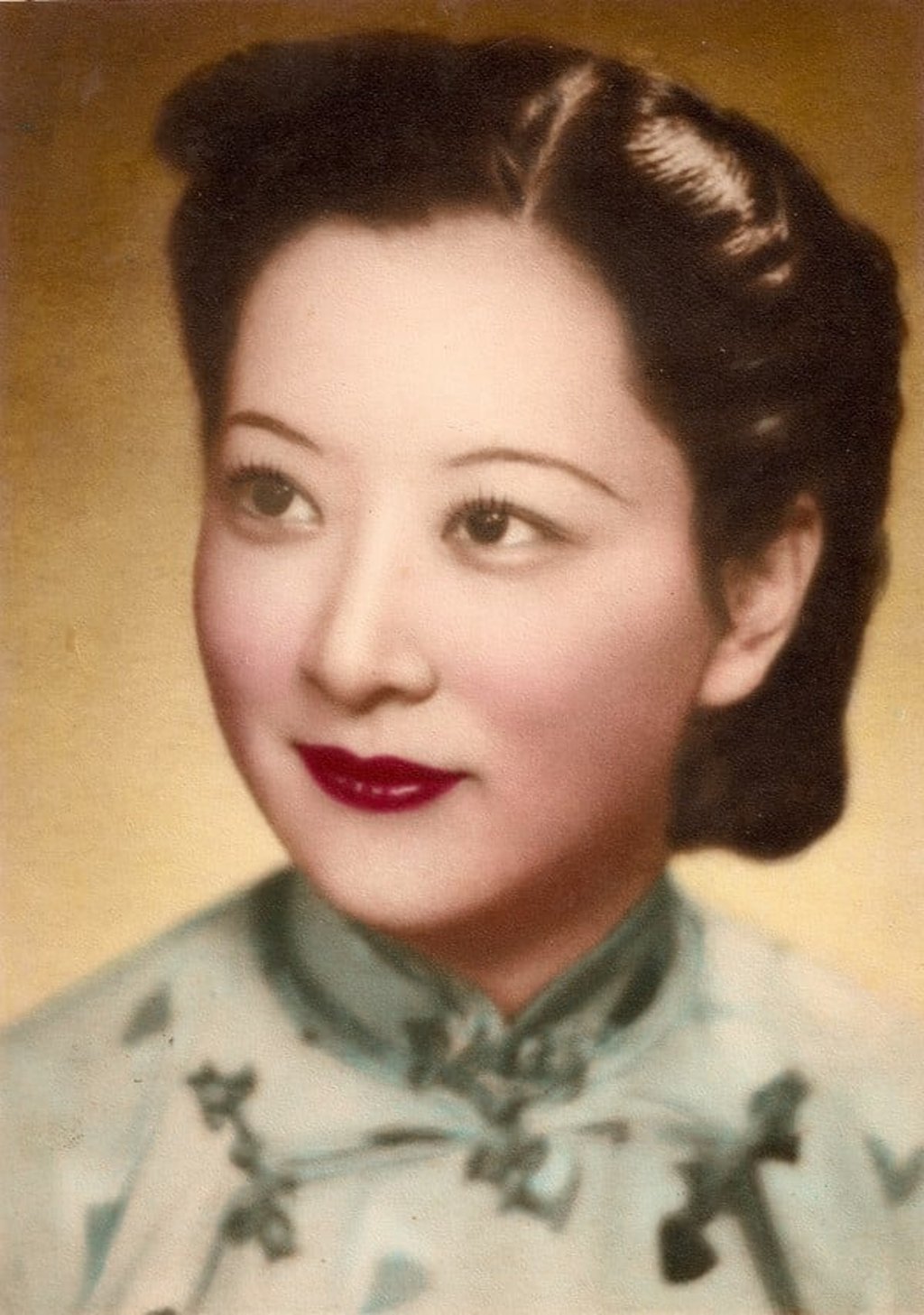

There was once a girl in Shanghai whose name was Sun Shuying but who was referred to within her family as either Third Daughter or Third Sister. Although she was born in the Year of the Sheep – 1931 – she looked like a plump little monkey; at least that’s what one of Eldest Sister’s suitors thought when he came courting under a balcony and saw Third Sister leaping about. “She’s totally annoying and you should ignore her,” was Eldest Sister’s yelled advice to her Romeo below.

Big sisters everywhere are like that and on the whole – so Third Sister always told herself when she looked back (which she didn’t tend to do, preferring to face forward) – there were plenty of happy moments in her childhood. She loved the symmetry of the rosewood baxianzhou or “eight fairies table” where the whole family – parents, grandmother and five children – could sit together, waited on by the servants.

It’s true there had been that time in 1941, when she was 10, that a Japanese officer had come to their residence in Lane 668. She had been on her own, listening to Deanna Durbin sing The Last Rose of Summer on a forbidden radio. He had demanded it be switched off, then he had looked around and asked for tea. Most people in the city only knew Shanghainese and the officer spoke in Mandarin but, luckily, Third Sister had already learned some at McTyeire School.

So they had talked. He had told her he had twin daughters her age in Japan. He had asked her if she would like to learn a song. Third Sister loved singing and the officer was delighted when she sang it back perfectly. He said she had done her family a great service and, indeed, she had – the officer requisitioned a different house in the lane for military use. That family had to move out within three days.

At school, Isabel was such a renowned storyteller that some of the younger girls would creep into her room to listen to her. When, in 2014, St Mary’s Hall compiled a collection of students’ reminiscences, one former pupil said of those 1940s nights, “Her self-scripted tales of love were wonderful and moving, simultaneously happy and painful so they made us shed tears. Isabel had this talent – it’s a pity she didn’t develop it.”