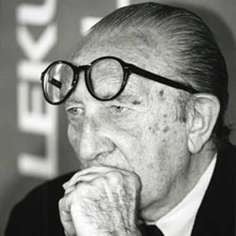

Spanish architect Rafael Moneo on working with his heroes

The Pritzker Prize winner, who is the subject of a retrospective in Hong Kong, says the only goal left for him is to make our lives better

SMALL TOWN, BIG WORLD VIEW I was born in Tudela, in northern Spain, in 1937. Although it seems paradoxical, I believe that growing up in a small town gave me a more complete perspective of life. A city child has a reduced view of the world, revolving around his home, his school; whereas a village child has more freedom, which allows him to understand the world better.

THE ROAD TO ROME I returned to Spain in 1962 to complete my military service and then won a grant to study for two years at the Academy of Spain, in Rome. Rome was a true discovery for me. I had travelled to Paris, to London and Scandinavia, but I didn’t really know the Mediterranean world. Since then, Italian culture has been deeply connected to my life. Coming into contact with the historians, scholars and architects in Italy completed my idea of a city where architecture is very important. Later in life, I was fortunate to work on the Roman Art Museum, in Merida (1985); a building that reflected the city’s ancient Roman roots. In its day, Merida was perhaps the most important Roman city in Spain, but it later became a predominantly agricultural city. I wanted the building to provide a glimpse of the ancient city that was once there, and built the museum space using Roman construction systems.