Review | Rudyard Kipling’s sadism and squalid sexual urges writ large in Sudhir Kakar’s novel of historic fiction

The Kipling File is a well-researched, elegant and highly readable fictional account of the young writer’s life in colonial India

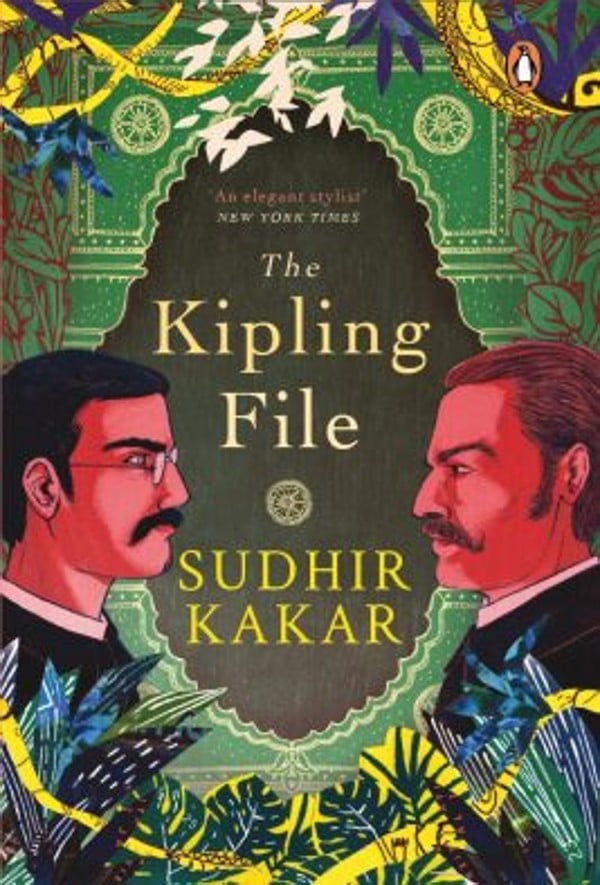

The Kipling File

by Sudhir Kakar

Penguin

For all its faults, British colonial rule bestowed a number of lasting benefits on India, from modern education and administration systems to a postal service and rail network that help connect the vast subcontinent.

There’s no lack of literary biographies of Rudyard Kipling, an unapologetic imperialist who was born in Mumbai, India, in 1865, and whose novels, short stories, children’s tales and poems have haunted the memories of generations. But it is rare to come across historical fiction about Kipling – and rarer still for an Indian to have written it.

Sudhir Kakar’s The Kipling File is a well-researched, elegantly written and highly readable interpretation of Kipling’s life in India. The author of five previous novels and 13 works of non-fiction, Kakar is a prominent Western-trained psychoanalyst known for his insights into Indian culture and the psyche of Indians.

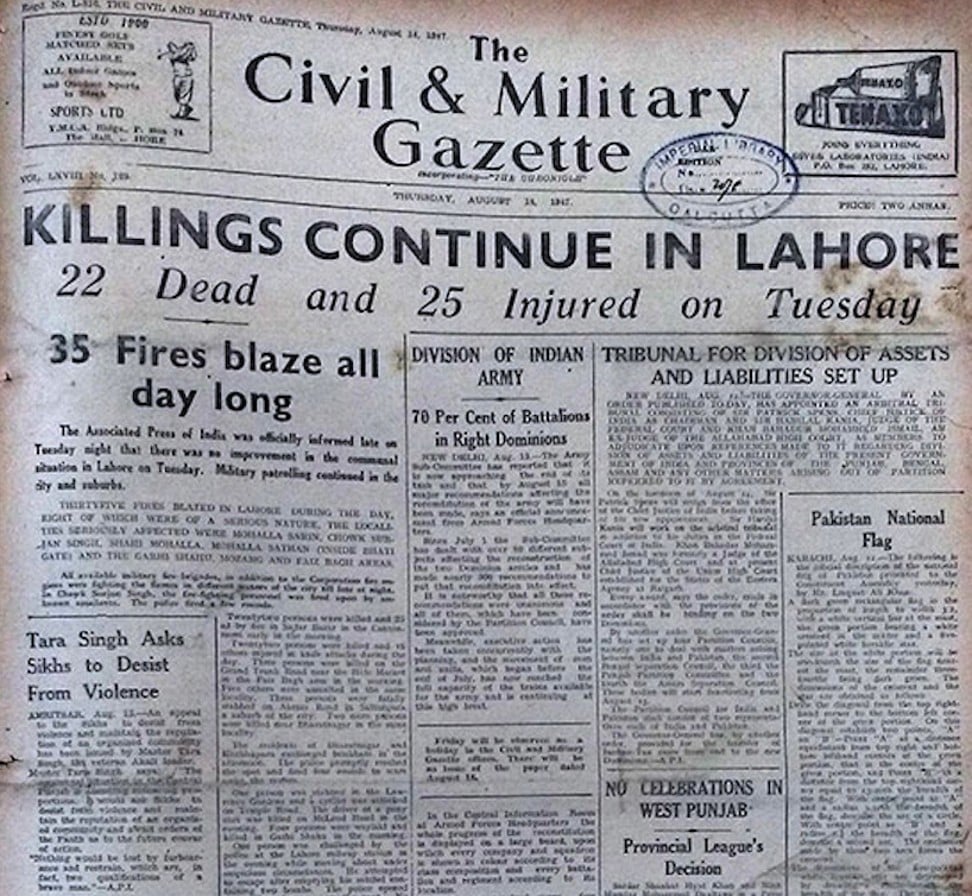

The 229-page novel, which begins in the mid-1880s, revolves around a friendship between Kipling and Kay Robinson, who was one of his editors at a fledgling Lahore-based daily called the Civil and Military Gazette.

Kakar tells his story through Robinson. The editor narrates events taking place about 30 years in the past, when Kipling was aged 16 to 23. This is the period before Kipling became famous and when he was known to be at his happiest. He spent most of that time in Lahore, in what Robinson calls the “Family Square” – a reference to Kipling, his parents and younger sister, Trix, who had many suitors, including the son of a viceroy.

Referring to Kipling by his nickname “Ruddy”, Robinson kicks off his reminiscences on a note that is as sombre as it is intriguing: “It is with a mix of admiration for the writer, fondness for the youth and revulsion for the man he has now become, that I have finally decided to pen my recollections of Ruddy,” writes Robinson.

Through the keen insights of his narrator, Kakar deftly captures the essence of life in 19th-century India, especially in the countryside. At one point, for example, Robinson poetically observes that dusk is decided not by the clock but “when the last puff of the day-wind brought from the unseen villages the scent of damp woodsmoke, hot cakes, dripping undergrowth and rotting pinecones”.

Kakar’s sharp prose [...] paints a portrait of an exceedingly eccentric man who went on to become one of the most famous figures of the British Raj

As the story progresses, we learn the reasons for Robinson’s strained friendship with Kipling. Robinson, who was Kipling’s best friend in India (and Kipling his), had long kept a secret from him: he wanted to marry Trix, of whom Kipling was fiercely protective. It further infuriated Kipling that Robinson was 13 years older than his sister, who was 18 when the editor first became infatuated with her.

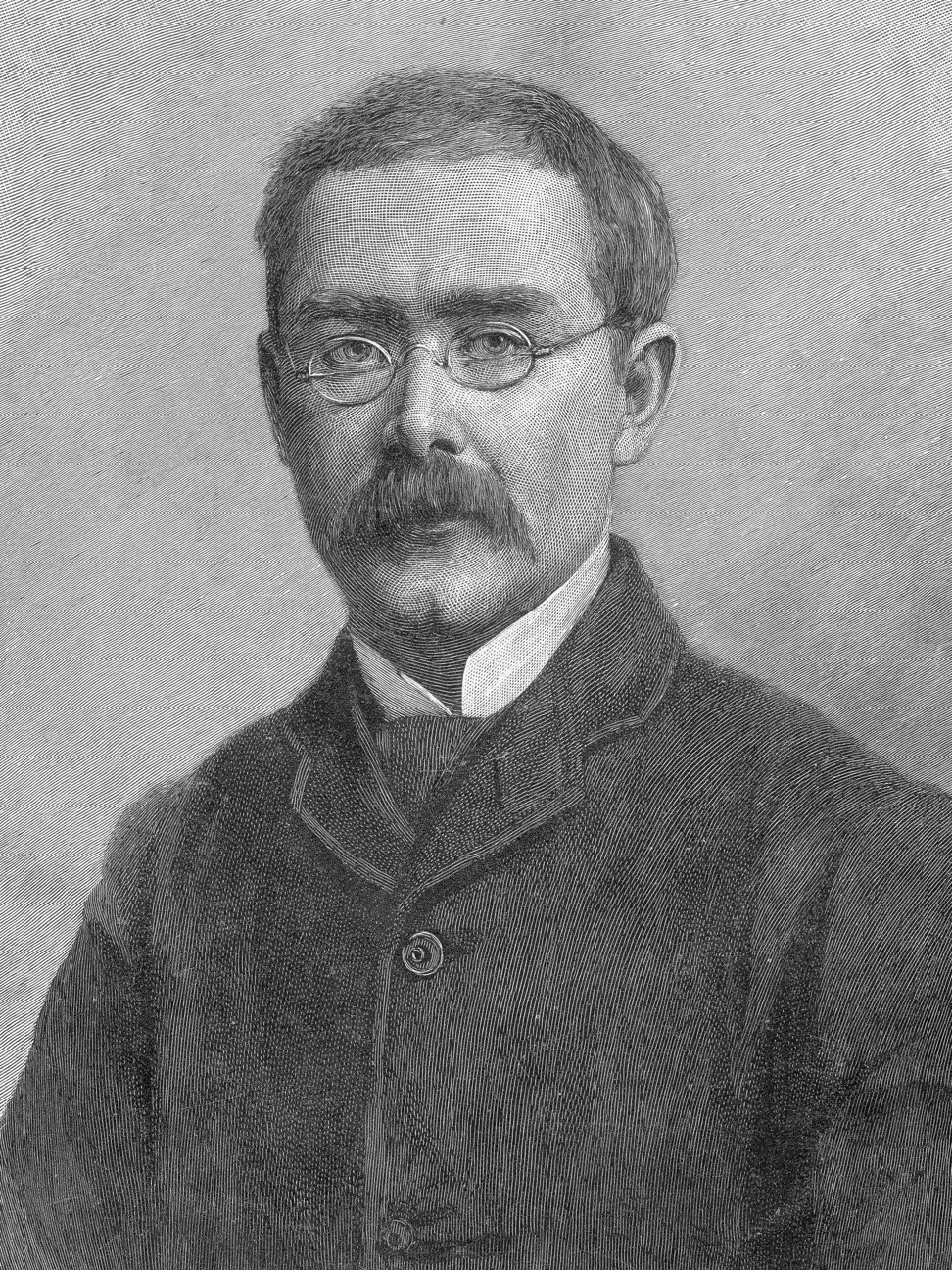

When Robinson first met Kipling, he beheld a “short, bespectacled youth who […] was the worst-tailored Englishman I had encountered since I left England’s shores. Scruffy, with not an inch that seemed to fit him, Ruddy made a bad first impression: a very small, very untidy and very mousey-looking young man, with exceedingly bright eyes shining watchfully behind round wire-framed spectacles.”

What’s more, Kipling “had a habit of dipping his pen frequently and deep into the inkpot, and as all his movements were abrupt, almost jerky, the ink would splatter”, Robinson tells us. And because Kipling usually wore a white cotton vest and trousers, the mass of inkspots on his clothes made him look like a Dalmatian dog. Through Kakar’s sharp prose, Robinson paints a portrait of an exceedingly eccentric man who went on to become one of the most famous figures of the British Raj.

A decade older than Kipling, Robinson thought so highly of the younger man’s literary gifts, both in prose and verse, that he deemed them wasted on everyday journalism. “Here in India, working on a paper which was far from flourishing, I discovered a journalist who had the power to make the fortunes of a London newspaper,” writes Robinson in his recollections, which he calls “The Kipling File”.

To enliven the paper and broaden the scope of Kipling’s journalism, Robinson encouraged him to write ballads, “some of which”, he recalled, “are now familiar to every schoolboy in the Empire”. Robinson featured Kipling’s short stories on the front and second pages of the Gazette, and they soon became popular with readers. Many of the stories were later published in books, contributing to Kipling’s literary renown.

“I pointed out to him how the simplest hack work and padding of the paper could be made bright and entertaining if he would only treat it from his own point of view,” Robinson observes. He also noted that Kipling’s talent for reproducing the minutest details owed less to a formidable memory than to his habit of taking rigorous notes – a “natural framing device for many of the 200 short stories he wrote in India”.

And yet, as Robinson points out, critics disparaged Kipling’s early Indian stories. His literature, they contended, was neither of the polite, drawing-room variety nor particularly aesthetic. Instead, it reeked of military barracks, horse stables and bar-rooms.

Robinson notes that Kipling’s talents “were lost on British India, where his readership was either too preoccupied with dry-as-dust official business, or too devoted to the frivolities of life”.

Robinson and Kipling had more than journalism in common. Both were nature lovers and loners who shared an affinity for solitude. Robinson thought of himself as a “tough romantic”, the kind of person who is at times indistinguishable from the “tender cynic” he believed Kipling to be.

“I could not know then that once we left India and I found my calling and retreat in the English countryside, the ‘romantic’ in my soul would bloom, whereas Ruddy’s move, away from the Family Square in Lahore and into literary fame in England, would dry up the wellspring of his tenderness, leaving weeds of cynicism and bitterness to grow rank and wild.”

In keeping with the widely accepted view of Kipling’s personality, Robinson depicts him as self-confident to the point of cocksuredness. But our narrator, following other commentators and biographers, also focuses on Kipling as a tortured soul who was deeply contradictory.

Kipling had a dark side that included a foul temper and more than a hint of sadism, which were elements of many of his stories. In the offices of the Gazette, Robinson witnessed Kipling throwing paperweights when lower-ranked staff entered his office without knocking.

“I could imagine that sometimes he gave his temper rein in his newspaper pieces,” Robinson recalls, “coating some of his sentences with the sharp edge of sarcasm intended to wound more than to amuse.”

Several of Kipling’s stories for the paper made Robinson uneasy. “Without being fully aware of it at the time, I sensed that their malice suggested the presence of a sadism that came to the fore in later years in some of his stories such as ‘The Moral Reformers’, in the collection Stalky & Co.”

In Robinson’s telling, Kipling also frequented the brothels of Lahore. He favoured poor, illiterate Hindu village girls, mostly child widows who were a burden on their families as they could not remarry due to religious reasons.

“God knows, I was far from a chaste monk,” Robinson writes. “Before marriage, during the hot months, I had had a couple of discreet liaisons in Lahore with attractive Eurasian girls. But to deliberately seek out, as Ruddy did, the lowest of native prostitutes in the most squalid of settings for the satisfaction of his sexual needs was beyond my comprehension.”

The Kipling File’s greatest strength isn’t so much its tactile prose, but the subtlety and sophistication that Kakar employs in re-evaluating his subject

It wasn’t just the dirt and disease. “For a long time I failed to understand how Ruddy, whose favourite words seemed to be ‘unclean’, ‘unkempt’, ‘filthy’, ‘loathsome’, ‘pestilential’, whenever he wrote about native quarters, who never missed an opportunity to turn in stories on the problems of sewage disposal and the diseases that lurked everywhere, could expose himself so intimately to what he otherwise loathed,” Robinson recalls.

“I could never understand how what disgusted him during the day could hold such an irresistible attraction at night,” Robinson writes. “However he might detest it by day, the lure of the native urban jungle at night, its overflow of life, its anarchic disorder, its overpowering smell of spices and woodsmoke, its frisson of lurking dangers and promise of intoxicating delights drew Ruddy in again and again.”

The Kipling File’s greatest strength isn’t so much its tactile prose, but the subtlety and sophistication that Kakar employs in re-evaluating his subject. Since his death in 1936, Kipling has been notoriously difficult to rediscover, not least because far too many biographers and commentators have been fixated on the man instead of his writing. Kakar’s narrator reminds us that although Kipling’s best work is born out of confusion and cruelty, it is also strangely beautiful and soothing.