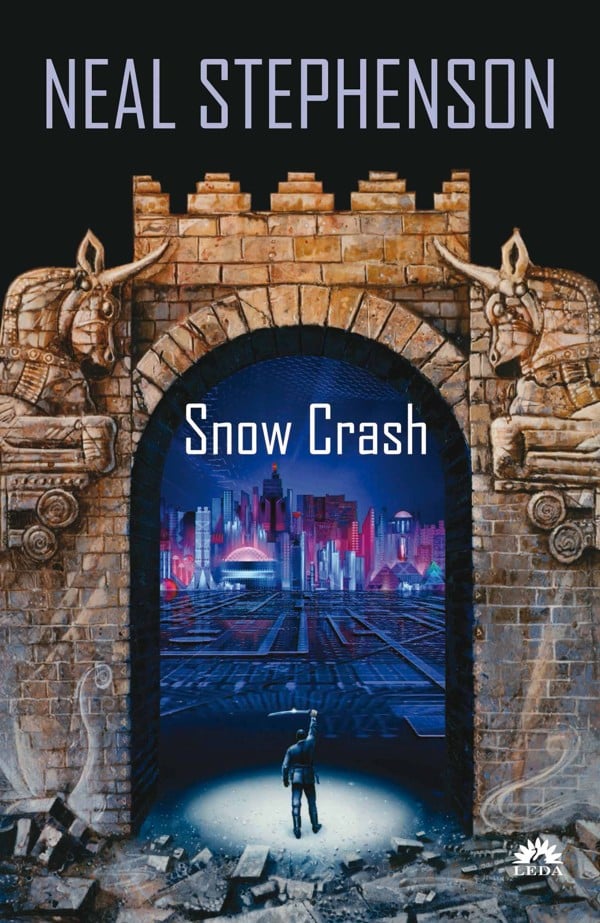

Hong Kong curator on how science-fiction novel Snow Crash gave him a taste of Asia

Neal Stephenson’s dystopic epic Snow Crash gave Tobias Berger, head of arts at Hong Kong’s new cultural centre, a new outlook on life and a thirst for new experiences

Neal Stephenson’s 1992 techno-thriller Snow Crash was uncannily prescient both technologically and politically. Set in a dystopian anarcho-capitalist future where state-like corporations run the planet, the book deals with a race to stop a deadly neuro-linguistic virus in a world that relies on a type of virtual-reality internet called the metaverse.

German-born Tobias Berger, head of arts at Tai Kwun, Hong Kong’s new arts and culture centre, and former curator at the M+ and Para Site arts centres, explains how the book changed his life.

Stephenson looked at Hong Kong very closely before he wrote the book [although set in the United States, Snow Crash depicts a society with numerous Asian cultural influences, with the oldest and most powerful of the corporate statelets known as Mr Lee’s Greater Hong Kong, while the book’s main character is half Japanese]. It got me very excited about the idea of Asia. It’s why I ended up here.

In the 90s we had television, certainly, but the internet had only just arrived, and in the West the general idea of Asia was built on books such as this, and films like Blade Runner [1982]. When I first went to Japan, in the late 90s, the only ideas I had about the country were geishas and scenes from Blade Runner.

Snow Crash was also full of ideas about the future – virtual reality, what Stephenson calls the metaverse – that felt like complete fantasy. I could only imagine both – Asia and virtual reality. They became the same thing: the other. This kind of science fiction showed my generation that some things from the imaginative landscape can become reality. It made people forward-looking in two senses: looking forward to something, but also looking ahead.

Final frontier: Hong Kong sci-fi conference pushes boundaries

I was very interested in promoting artists like this because of what I learned from Snow Crash. You can’t predict the future, but you can try to shape it a little bit. Books like that – and films, and songs – have had an immense influence on the way we shape the future.

When you read something and think you understand it, but later discover it means something else, it really gets you thinking. This gives me so many ideas – a lot of productive misunderstandings. That’s the great joy of science-fiction literature.