Review | Hope, conflict, struggle: Chinese-American experience laid bare in elegant debut novel

Number One Chinese Restaurant is an acutely observed character study of friendships forged in a fiery workplace

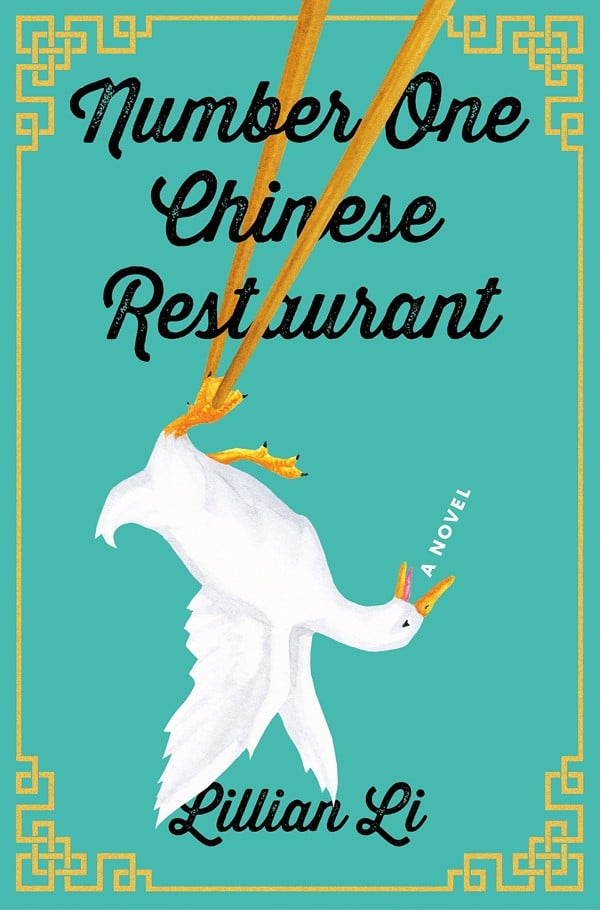

Number One Chinese Restaurant

by Lillian Li

Henry Holt and Co

As Lillian Li’s debut novel opens, with a scene in a Chinese restaurant in America, a group of waiters are singing Happy Birthday. They are horribly out of tune. As the song fades and the customer blows out the candle on her complimentary cheesecake, the waiters retreat to their tables, still applauding. “We need great leader,” one of them says dejectedly as their unpopular boss sits nearby.

At once darkly comical and beguiling, the chaotic scene sets the stage for a multigenerational novel whose Chinese-American characters are brought together by friendship and love, as well as their hopes, frustrations, conflicts and struggles in their place of work.

Number One Chinese Restaurant is set in the Beijing Duck House, a fictional eatery in the city of Rockville, near Washington, DC. Decorated in a deep, matte red, its walls are lined with framed photos of famous customers, including Hollywood actors, politicians and former presidents.

The restaurant is run by two brothers, Jimmy and Johnny Han, who took over after the death of their father, an immigrant from Beijing.

Jimmy is an ambitious but impulsive former cocaine dealer who manages the nuts and bolts of the business, having worked there for 20 years, many of them as a waiter himself. He keeps waiters’ tips and forbids them from speaking Chinese in the dining room. “No one called him ‘great leader’,” Li writes, and behind his back the staff refer to him as “little boss”.

Johnny, by contrast, has never strained his back waiting at tables in his seven years with the Duck House. Principled, thoughtful and circumspect, he runs the restaurant’s front-end operations – when he’s not pursuing lab research in Hong Kong (a storyline that’s curiously hardly explored in the novel).

Jimmy runs a tight ship. Whenever he sees waiters talking to each other, he scolds them and orders them back to their tables. He delays their lunch breaks and forces them to go on a week’s unpaid leave if they make mistakes.

The pressure of working at the Duck House is especially acute for the children in these so-called “restaurant families” – kids such as Johnny’s daughter, Annie. A joke cracked by Annie perfectly summarises the situation: every day at a Chinese restaurant is bring-your-kid-to-work day. Once in the restaurant, parents aren’t parents any more. And waiters are not really people but “more like cartoons”, as she puts it.

The fate of the Beijing Duck House drives much of the novel’s narrative, told through the voices of several main characters. Rather than continue his father’s tradition of serving authentic Peking duck, Jimmy wants to sell the Duck House and open Beijing Glory, an Asian fusion restaurant in a more upscale neighbourhood, with cheaper Peking duck and Americanised Chinese food on the menu.

There’s just one problem: Uncle Pang, a family friend and nine-fingered fixer who helped launch the Duck House. Pang, who gets a share of the Duck House’s profits, is instrumental in finding a place for Jimmy’s new restaurant, but fears he’s not going to see any income from the Glory.

To get revenge, Pang hires Pat, a brash, 17-year-old dishwasher and trainee waiter at the Duck House, to burn the restaurant down. A high-school dropout and budding alcoholic, Pat is the only son of the good-humoured single mother Nan, the restaurant manager, whose definition of friendship at the Duck House is “the natural occurrence between people who, after colliding for decades, have finally eroded enough to fit together”.

It’s common knowledge at the Duck House that Pat has been having a dalliance with 19-year-old Annie, who works as a hostess at the restaurant. After a night of drinking, Annie helps Pat set the fire, but when Nan finds footage of the crime on her son’s mobile phone, Johnny turns him in to the police.

A distraught Nan then confronts Johnny: “You took my son away in handcuffs. You made me watch. I can do the same thing to you.”

Johnny gets down on his knees before Nan, digging his fingers into the carpet in her home. “He felt like an animal and a fool, and in his shame he was able to force this vibrant, terrifying part of himself to lie back down,” writes Li. Wiping his sweaty brow, he says to Nan: “You do what you think is right.”

“If I do what is right, your daughter goes away,” Nan replies, taunting Johnny in one of the novel’s most dramatic moments. “You want to send your baby girl to prison?”

Incredibly, Johnny insists on doing just that. Reporting his daughter, even though she’s an adult with a prior police record, seems to appeal to his vanity.

Li’s complex characters may remind readers of those in the acclaimed short stories of Flannery O’Connor, one of America’s greatest fiction writers. And Li is the kind of author who, to quote O’Connor, is “interested in what we don’t understand rather than in what we do” – the kind of characters who are “forced out to meet evil and grace and who act on a trust beyond themselves”.

A graduate of Princeton University, Li’s exquisite observations of restaurant life were inspired by her own stint as a waitress at a Peking duck restaurant in the state of Virginia.

“The experience was so challenging, both physically and emotionally, that she lasted only a few weeks before throwing in the towel,” according to the novel’s publisher, Henry Holt. “But long after the ache left her fingers and feet, she felt the deep loneliness and alienation of waiting on people who looked right past her.”

Eventually, the Beijing Duck House is rebuilt. By the end of the novel, it becomes clear that Li is using it as a metaphor for China, especially the nation’s culture and values

Although Number One Chinese Restaurant is a local and temporal novel, the stories of its owners and workers echo with a universal relevance.

Parts read like prose poems. Contrasting his quarter-century-long marriage with that of the typical American, one veteran Duck House customer offers this almost Taoist meditation: “Americans. They believed a strong marriage came from knowing their partner’s every shadowy thought. But it was knowing too much that killed love.”

He adds: “Marriages were torn apart by empathy … Intimacy was not to know but to wonder. Eyes that searched in their staring were the hallmarks of every lover’s gaze. And if the search was lazy, unstructured – a slow, easy stroll rather than a rush to the finish – then in this stretch of time, forever might comfortably rest.”

Eventually, the Beijing Duck House is rebuilt. By the end of the novel, it becomes clear that Li is using it as a metaphor for China, especially the nation’s culture and values as reflected in the grit, determination and hard work that has enabled generations of Chinese immigrants to provide for their families and find success in America.