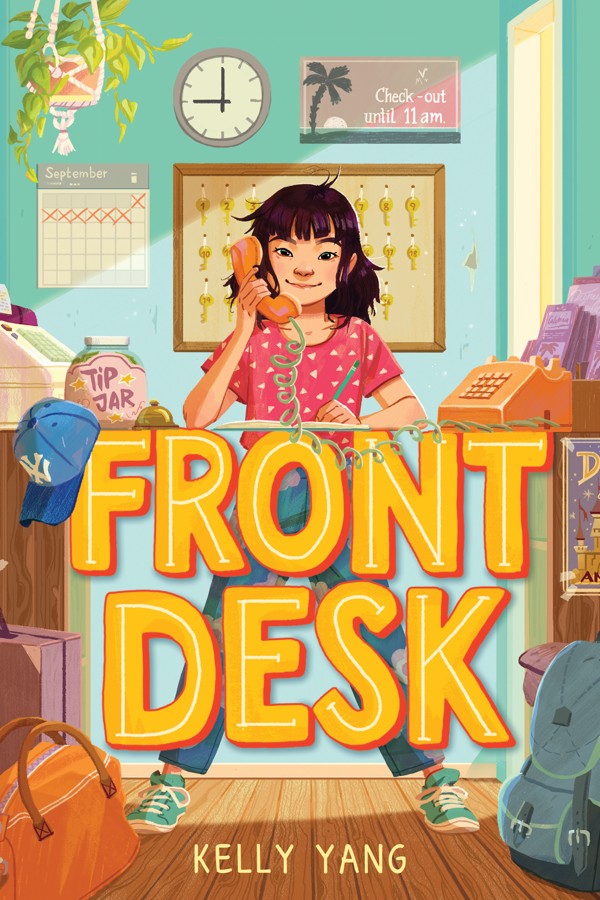

Kelly Yang mines her experience as child immigrant in US for touching debut novel

Front Desk recounts the highs and lows of a family-run motel as seen through the eyes of a former 10-year-old desk clerk – as the author, a Harvard Law graduate who teaches writing skills in Hong Kong, once was herself

There’s a moment in Kelly Yang’s debut novel, Front Desk, when 10-year old Mia Tang is being mocked for wearing second-hand floral trousers. It’s California in the early 1990s and the rest of the kids at school are in jeans, but Mia’s stuck in a pair of thin, pyjama-like trousers that her mother bought in a bundle at a charity store.

It’s a small scene but, for Yang, who was also dressed in charity shop floral trousers as a young girl in California, it was one of the hardest to write.

“We bought all our clothes at the Goodwill. I still have classmates who, when I reach out to them on Facebook, they say, ‘You’re the girl with the weird floral pants.’”

Yang’s childhood serves as the basis for Front Desk, a novel for readers aged eight and above. Like Mia, Yang immigrated with her parents from China to the United States, moving around until her parents ended up managing a motel.

Yang also worked at the front desk as a 10-year old, helping her parents with customers, developing friendships with the “weeklies” and solving any number of problems that pop up in the motel business. Also like Mia, Yang had a love of reading and writing, and frequently turned to her library as a source of information.

One of the big troubles I had growing up was with my parents telling me I couldn’t make it as a writer. They would say, ‘You were not born with this language, how can you be the best?’ They called it the ‘white kids’ language’

But while Front Desk ends with Mia staying in the family business, Yang was accepted to the University of California, Berkeley, at the impressively young age of 13 before going to Harvard Law School. After graduating in 2005, Yang moved to Hong Kong and turned her focus back to writing. She opened the Kelly Yang Project, a writing and debate programme, in the city in 2005.

“I had always been thinking about how I would tell this story,” Yang says. “It was just sort of a crazy childhood. I toyed around with an adult book and a memoir, and I just kept getting stuck.”

It was her eldest son who helped lead her to middle-grade young adult fiction. Yang was trying to encourage him to read and so, in the summer of 2015, she wrote a chapter a day for them to read together. She finished the book and soon found an agent.

“I had not written for middle grade before and I had no idea what I was doing,” Yang says. “The first version was very light, very funny and almost kind of slapstick. It was designed for my son, to get him to read to the next page. That was the only goal.”

But Yang’s editor saw the potential for more than just the funny bits. Apart from two scenes, Yang rewrote the novel, making her characters deal with bigger issues than the daily running of the motel. Yang thought the book was finished, but American politics made her think again.

“The election really affected me,” she says. “I had thought we were pretty much done, but then the world changed and I was thinking about what it’s like to grow up in America today. I was thinking there is so much more potential for a deeper story if I have the courage to do it.”

As a kid, I remember having so many customers be wrongly accused because of their skin colour

Yang rewrote most of the book a third time, making the story not only about Mia, but about immigration, race, discrimination, poverty, education, language barriers and, ultimately, hope.

“It’s infused with a lot of autobiographical details,” she says. “We definitely dealt with racism and poverty, and the police coming over and asking us questions or asking the customers questions. After the Los Angeles riots [in 1992], there was a lot of discrimination, especially in small businesses. [My parents and I] were really upset about this – this was not our feeling of America.”

Yang is hoping her book will help readers understand the importance of diversity, tolerance and empathy.

“As a kid, I remember having so many customers be wrongly accused because of their skin colour,” she says. “We had a lot of customers living in a motel for a really long period of time because they didn’t have any other home. You get to know them and sometimes it comes down to really horrible little misunderstandings and injustices. But these were wonderful people who protected my family.

“Stuff like that is still happening today. I hope the book shines a light on what everyone can do about it, even someone who is 10 years old and an immigrant.”

“One of the big troubles I had growing up was with my parents telling me I couldn’t make it as a writer,” Yang says. “They would say, ‘You were not born with this language, how can you be the best?’ They called it the ‘white kids’ language’.”

But, with the support of teachers and librarians, Yang excelled. When she got the chance to go to university at the age of 13, she grabbed it.

“I was only making so much at the front desk,” Yang says. “The ending of the book is sort of a wishful ending, but that didn’t happen. My parents became unemployed, we had to live sparsely without any savings and it was scary. I thought that if I went to college early, I could get out early and start making money. It’s not something I would recommend to most kids.”

There are so many people going through so much and having so many different experiences. We have to talk to each other so that kids don’t grow up feeling abnormal

Yang’s book is sensitive and kind, and she was able to keep a lot of the laughs. Despite the novel’s deep underlying themes, Yang keeps the story moving, allowing Mia to go from one adventure to the next. Maintaining the book’s pace was important to Yang, especially when she gave the final version to her son.

“My concern was that he wasn’t going to keep turning the page,” Yang says. “When I saw that he was reading it and I couldn’t pry it out of his hands, that led to a lot of deeper conversations about my childhood, because he was like, ‘Wow, this is different. Is this real?’ I think he was surprised and intrigued, and it’s given him a lot more empathy.”

Yang hopes the book encourages people to talk to one another.

“The message is that there are so many people going through so much and having so many different experiences,” she says. “We have to talk to each other so that kids don’t grow up feeling abnormal or that they are not going to amount to anything because their narratives are so different.”