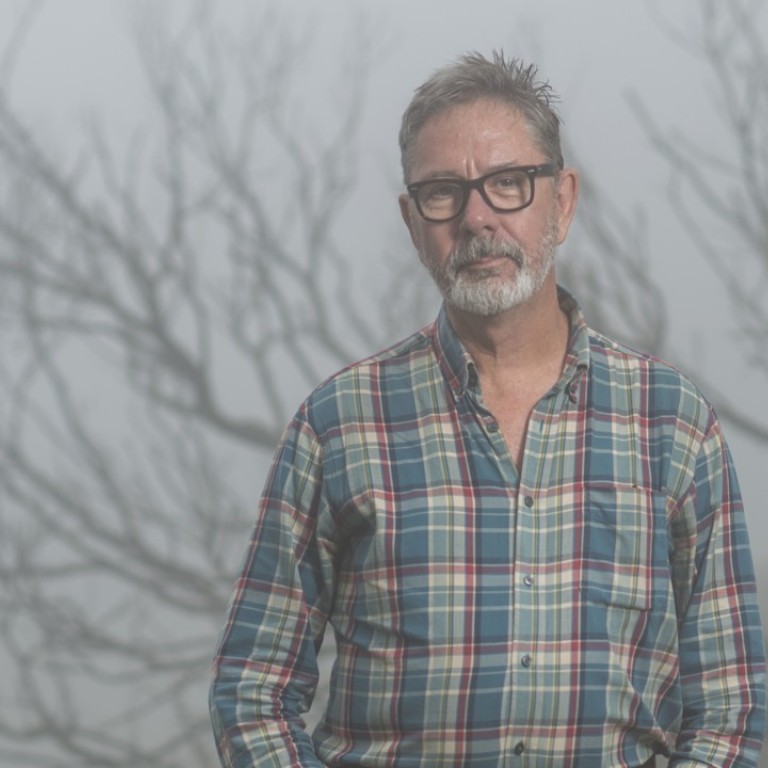

Hong Kong mountaineer-turned-businessman on close encounters with death

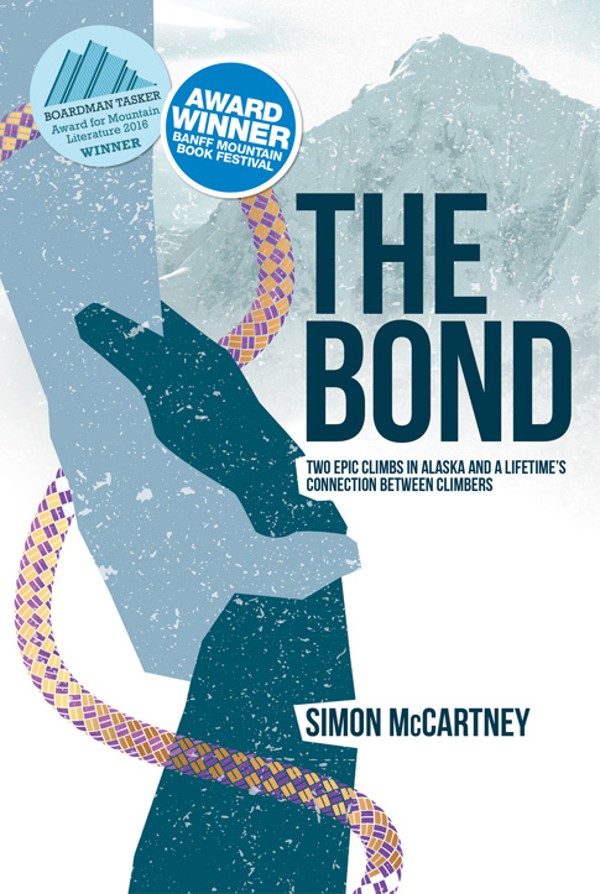

Simon McCartney was once an accomplished mountaineer, and his profound friendship with fellow climber Jack Roberts – as well as their arduous expeditions in Alaska – is explored in his memoir, The Bond

LEARNING THE ROPES I was born in London in 1955. My parents got divorced when I was six and both remarried, so I had two sets of parents and four opinions to weigh in on any issue. I spent weekends with my father and weeks with my mother. My dad thought a bit of adventure would do me good and introduced me to a group that organised rock climbing, potholing and caving.

From the age of 14, I climbed every weekend, beginning with a small cliff near London and then hitchhiking to Wales or the Peak District with ropes in my backpack. I liked being in the mountains, but it was the risk that I really liked, and I used it as a measure against my peers. I enjoyed doing better than others – I’m unremittingly competitive.

Just before my A-levels, I had a spectacular accident: I fell 40 feet onto the road in Cheddar Gorge and fractured a couple of vertebrae. I was in plaster from my groin to my neck. With nothing else to do, I inadvertently did better in my A-levels than I would have otherwise.

Dave left and I hung around, and that was when I met an American climber, Jack Roberts, in a Chamonix bar. It was a meeting that would change my life. We decided to go to the UK and climb for a week. Over a beer one night, he convinced me that I shouldn’t go back to the Alps the following summer and instead go to Alaska with him and make first ascents. Alaska was still relatively untouched compared with the Alps, which sounded great to me.

DRAMA ON THE NORTH FACE The cover of Mountain magazine showed the north face of Alaska’s Mount Huntington and said it had never been climbed because it was very dangerous. That was a red rag to a bull, and Jack didn’t say no.

A ski plane dropped us onto a glacier and we looked up at the monster. It’s not like being in the Alps, where if you don’t like it you can walk back to the pub – we spent a month living in snow holes. We had one go at the north face and nearly got killed by avalanches, surviving by hiding under an overhang. I was 22 and believed I was immortal.

We had pulled off easily the hardest climb in Alaska and then we did what all climbers do: we drank a lot, sliding beer bottles down the bar like we were cowboys

On July 1, 1978, the weather was great. We spent the morning sunbathing, and then Jack and I just went for it. It took us longer to get up than we thought and we barely survived two avalanches. At the summit, I fell through a cornice – a meringue of snow. It was idiotically dangerous but we did it and no one has climbed (the north face) since.

When we got to the top, we realised we couldn’t return the same way and had to descend the west face, which we knew nothing about. Luckily, a Japanese group had left fixed rope behind and we were able to follow that. Then our rope got jammed, leaving us with just 80 feet of rope. We had to use bits of the sh**ty nylon rope left in the ice by the Japanese, and it took us 54 non-stop hours to get down and another 24 hours to get back to base camp. We radioed and our pilot picked us up off the glacier.

We had pulled off easily the hardest climb in Alaska and then we did what all climbers do: we drank a lot, sliding beer bottles down the bar like we were cowboys.

UP THE EIGER IN WINTER We went to California and Jack hurt his back in a stupid bouldering accident. Once back home, I decided I wanted to climb the Eiger and to do it in winter because it would be harder.

Six of us went and we all ended up on the north face of the mountain at the same time. It was minus 30 degrees Celsius in the daytime and so cold that the tips of our ice axes were breaking off. We got into a terrible mess because we needed 12 ice picks for six of us to climb, and that dwindled down to four, making progress impossible. I got frostbite. We got close to the summit but had to be rescued by helicopter, which was exciting. But I did end up climbing the north face of the Eiger that winter.

We spent 29 days on the mountain and we did get up it, but at great cost. Jack got frostbite badly and I got cerebral edema, which is a progression of altitude sickness: your brain swells up inside your skull, creating cranial pressure and the shutting down of functions such as talking and balance. Before we got to the summit, I collapsed and we spent a few days there. Jack was tearing himself to pieces about whether to stay and both of us die, or to leave me and go for help. Just as he was leaving, two people turned up. One of them, Bob Kandiko, stayed with me and we ended up descending the way he’d come up the southwest face.

As we descended, I began to recover, but on the way back Bob took a fall and I tumbled past him – we were tied together – and fell upside down in a crevasse. A climber who was nearby pulled me out.

LIGHTING UP THE HARBOUR I lost touch with Jack, got married and, in 1982, I moved to Australia and gave up climbing. We lived in Sydney. I got a job in the ski industry, which was heaven because I could ski every weekend, but in the end I couldn’t stand working for the company and found work with a marine operation, but they weren’t doing so well.

I’ve got a fear of heights now – I wear a harness when I go to the edge of a building

I worked in television for a while and then got a job with a company called Laservision that used lasers for entertainment. I did design for them.

One day in 2002, Hong Kong’s commissioner for tourism, Rebecca Lai, walked into our office and we sold her on the idea of lighting tall buildings. We ended up winning the contract for the Symphony of Lights laser show in Victoria Harbour.

FEAR OF HEIGHTS I stuck it with Laservision a little longer and then, 12 years ago, I moved to Hong Kong when my colleague Peter Kemp and I started Illumination Physics, lighting casinos in Macau. We also did the lights on the HSBC Building, in Central.

I didn’t hear of Jack until 2012, when he died in a climbing accident. He was 59 years old. I decided to write about our time in Alaska and the book The Bond came out last year. I’ve got a fear of heights now – I wear a harness when I go to the edge of a building. The only risk-taking I’ll do these days is in business.