Review | Book review: China, US bound by suspicion and hope

John Pomfret’s history of the friends-to-allies-to-enemies-and-back-again relationship between China and America is a masterful account of the ties that have shaped the foremost powers in the world today

The Beautiful Country and the Middle Kingdom: America and China, 1776 to the Present

by John Pomfret

Henry Holt and Co

Burlingame set up residence in a courtyard near the Forbidden City, the entrance of which was so narrow that visiting dignitaries had to get down from their sedan chairs in the street and drag their gowns through the mud. It marked an inauspicious start in the country for a man who would resign as a US diplomat to become “minister plenipotentiary” on the first major Chinese delegation to the West.

Nowadays, there is a growing sense that no problem of global concern – whether it be global warming, economics or the proliferation of nuclear weapons – can be solved without Washington and Beijing working together. One hundred and fifty years ago, however, just 90 years after the US was founded, the idea that one of the world’s youngest nations and a country then struggling to exert itself against foreign powers would one day be the main global rivals would have seemed farfetched, to say the least.

In his new book, John Pomfret, a former China correspondent for The Washington Post and author of Chinese Lessons: Five Classmates and the Story of the New China (2006), examines this often-strained relationship, tracing periods of optimism, xenophobia, anger, alliance and uncertainty as the two countries have gone from being friends to allies to enemies and back again. Key figures on both sides, including Burlingame, are fleshed out while missed opportunities to alter the trajectory of the relationship are scrutinised.

On the American side, China appeared to be a nation primed for Christianity and also a vast opportunity for those with business acumen and ideas; many American fortunes were made on the back of Chinese trade.

Throughout the book we see the ways the countries have affected each other, in literature, technology, trade and cuisine. By the 1920s, the US was hosting more Chinese students than the nations of Europe combined. After the Communists came to power, American-educated Chinese built China’s first satellites, designed its first intercontinental ballistic missile and brought nuclear physics to the country. “From 1949 to 1956, 129 Chinese students and scholars from the United States went to work in the elite Chinese Academy of Sciences, where they accounted for more than a quarter of all its top slots – at a time when Soviet scientific principles were supposed to reign,” writes Pomfret.

This has continued: from Deng Xiaoping onwards, every Communist leader has sent at least one of his children to the US to study, “including the Harvard-educated daughter of the current president, Xi Jinping”.

Yet, for all the interaction, Pomfret makes clear that few Chinese have truly understood the US and few Americans have really got under the skin of China. The relationship has been one of mutual disappointment. For much of their combined history, many Chinese have held out hope America will guide their country towards a better future – only to be disappointed. On the other hand, many Americans have waited in vain for a democratic, Christian China to take its place at the top table.

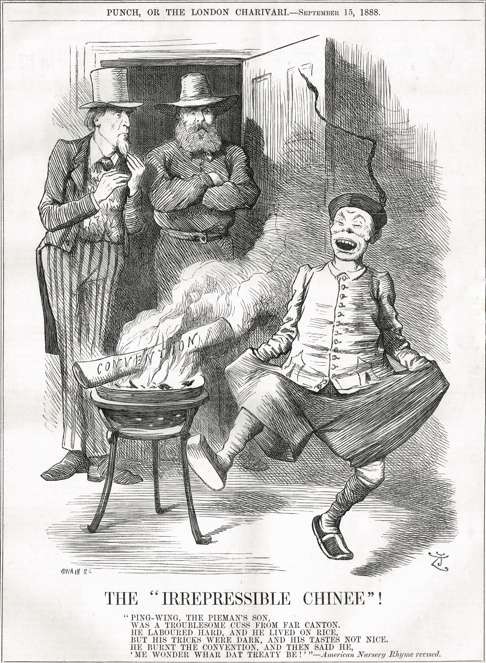

Pomfret describes it in terms of a Buddhist cycle of reincarnation. “Both sides experience rapturous enchantment begetting hope, followed by disenchantment, repulsion and disgust, only to return to fascination once again.”

While attention is paid to the impact of trade, as well as religious, educational and cultural interactions, it is the political entanglements between the two nations, especially in the past century, that form the book’s spine.

Following the end of the first world war, when China was treated with near contempt during the treaty negotiations, the relationship spiralled downwards. “Historians have debated whether the United States lost China at the end of the second world war, but it clearly lost a part of China in 1919,” writes Pomfret. And where America failed, Russia stepped in.

The second world war saw the almost total breakdown of relations, as American politicians and generals prioritised their own country’s needs, often with damaging repercussions to the Nationalist Chinese government, while US diplomats grew increasingly despondent with the corruption they saw among the Beijing leadership. After 1949, the nations were squaring off as enemies.

Despite its depth, this isn’t a simple history, and it takes the relationship through president Richard Nixon’s historic visit to China in 1972 up to the present day, with China now increasingly wondering, as a bona fide superpower, what its relationship with America should be, and vice versa.

The book is sweeping in scope but nonetheless manages to paint a vivid picture of personal interactions, adventures and misadventures.

Looking at developments the two countries through the prism of Sino-American relations can, at times, feel dismissive of the roles played by Britain, Russia and other nations. But that is a minor quibble with such a deeply informative work.

Examining the relationship between two countries as vast and complicated as the US and China takes stamina, yet as the world increasingly revolves around the interactions of these two superpowers, it is important to understand how their relationship has developed, succeeded and failed over the past 240 years.

Pomfret does a masterful job of presenting the good, the bad and the ugly from generations of interactions.