- Katharine Jowett became a prolific painter of Beijing in the mid-20th century, but a lifetime of shunning the limelight saw her works fall into obscurity

British artist Katharine Jowett is little remembered today, but in the mid-20th century she was extremely popular for her oil paintings and woodcuts. But not in Britain. She would come to be known as one of only a few Western female artists who chose to live and work in Japan, Korea and northern China in the years between the two world wars.

Jowett’s informal cohort included Americans Helen Hyde, Lilian May Miller and Bertha Lum, along with Scottish artists Elizabeth Keith and Anna Hotchkis. Never to meet as a formal salon, the artists all shared an interest in shin-hanga, or the “new prints” movement in Japanese art, which had revitalised traditional woodblock printing techniques of the earlier Ukiyo-e school.

While some did know each other personally or had crossed paths at exhibitions, most of these artists only knew each other through comparisons of their work.

Hyde – born in 1868 in New York state, and who parlayed her training at art schools in California, Berlin and Paris with time in the atelier of the Japanese artist Kano Tomonobu – was the most established. She was also the oldest, and died in 1919 just as several others were first visiting the region.

Miller, born in Tokyo in 1895 to an American diplomatic family, was introduced to engraving and woodblock printing by Hyde in Tomonobu’s studio. Keith, born in 1887, had travelled from Scotland to Japan, where she studied shin-hanga techniques before sojourning in Beijing for a time.

Fellow Scot Hotchkis, born in 1885, went to China to visit her sister, working in a YWCA-funded girl’s school in Shenyang, northeast China, but stayed on after being offered an art-teaching post at Beijing’s Yenching University. She worked mostly in oil paints and occasionally printmaking and established her own studio in a secluded traditional hutong lane.

Also in Beijing was Lum, born in 1869, with her own hutong studio close to the Forbidden City. Lum had studied woodblock printing techniques in Yokohama before World War I, and combined the Japanese techniques with her immediate surroundings to reproduce Beijing scenes.

But it is Jowett for whom, despite having the most significant body of work among them, personal information is most difficult to find. We can track the few mentions left behind in The Peiping Chronicle, very occasional references in the British press, the few remaining records of the Peiping Institute of Fine Arts, or auction houses and gallery notes.

Her only prominent collector was the 20th century American connoisseur and scholar of shin-hanga Robert O. Muller.

Like many “amateur” artists – in the sense she seems not to have considered herself a professional at all despite the quality, quantity and profitability of her output – Jowett has become obscured by lack of her own self-promotion.

In the West, Jowett is generally perceived, when she is regarded at all, as a charming capturer of northern Chinese scenes, whose pieces occasionally pop up at auction for affordable prices or, invariably unattributed, on Instagram or Pinterest.

If Jowett’s reputation in China since 1949 has survived at all, then it is partly due, so unverified rumour has it, to the fact that a series of her portraits of Beijing landmarks were supposedly the only Western art to adorn the walls of Mao Zedong’s personal rooms at the Zhongnanhai leadership compound.

Katharine Alice Wheatley was born in 1883, to a Methodist family in Devon, southern England. Originally from Yorkshire in northern England, her father was a minister who moved to the West Country to take charge of a congregation in Exeter.

Katharine proved a headstrong girl and in her late teens fell in love with a missionary and pursued him all the way to Asia, and, as one might expect, China blew her mind. Trailing the object of her obsession through Hubei and Hunan provinces she soon realised he was not the man for her and the missionary life not as exciting or fulfilling as she had imagined.

Katharine retreated to Peking to consider her future. There, she met a man called Hardy Jowett, originally from Bradford in Yorkshire but who had arrived sometime in the mid-1890s as a Methodist missionary posted to Wuhan in central China. The pair married in 1910, when Katharine was 27. They decided to return to England for a furlough, travelling via Japan and Canada as a honeymoon.

It was a trip that almost proved disastrous as they were nearly shipwrecked soon after leaving Yokohama, caught in a 60-mile-an-hour (97km/h) gale. The ship limped into harbour at Victoria, British Columbia, eight days later. Their brief stay in England saw them lodging in London long enough for Katharine to give birth to their first son, Christopher. A second, Edward, would soon follow.

In World War I, Hardy’s Chinese linguistic expertise was put to use in France, where he became a commander of the Chinese Labour Corps (CLC), most from Shandong province, recruited by the British government. After the armistice, Jowett’s service lasted into 1920, as the CLC were given the gruesome task of “clearing up” the battlefields across France and Belgium.

Eventually the family returned to China. Hardy left the church and became the Beijing manager of the Asiatic Petroleum Company. It was a prestigious job and his income was sufficient to allow Katharine to pursue her dream of becoming an artist.

According to the scant records that remain we know that Hardy was on the board of the Peiping Institute of Fine Arts where Katharine volunteered. The institute hosted exhibitions and ran classes in all forms of visual art and Chinese crafts, along with classical music recitals and theatrical productions. Its annual ball was considered a major social highlight by the city’s foreign residents.

From the fading social columns of The Peiping Chronicle we know that, through the exhibitions of the Peiping Institute and the few professional art galleries in the city, Katharine Jowett would have seen the work of the earlier shin-hanga-esque practitioners Hyde, Miller, et al. Jowett’s earliest dated works are oil paintings and watercolours, but she soon moved on to specialise in woodcuts and linocuts, likely due to that exposure.

Jowett and Lum exhibited together at several Peking galleries and were both keen members of the Peiping Institute. Lum was about 15 years older, an extremely energetic and productive artist who, in 1912, had been the only foreign artist to appear in the Annual Art Exhibition in Tokyo.

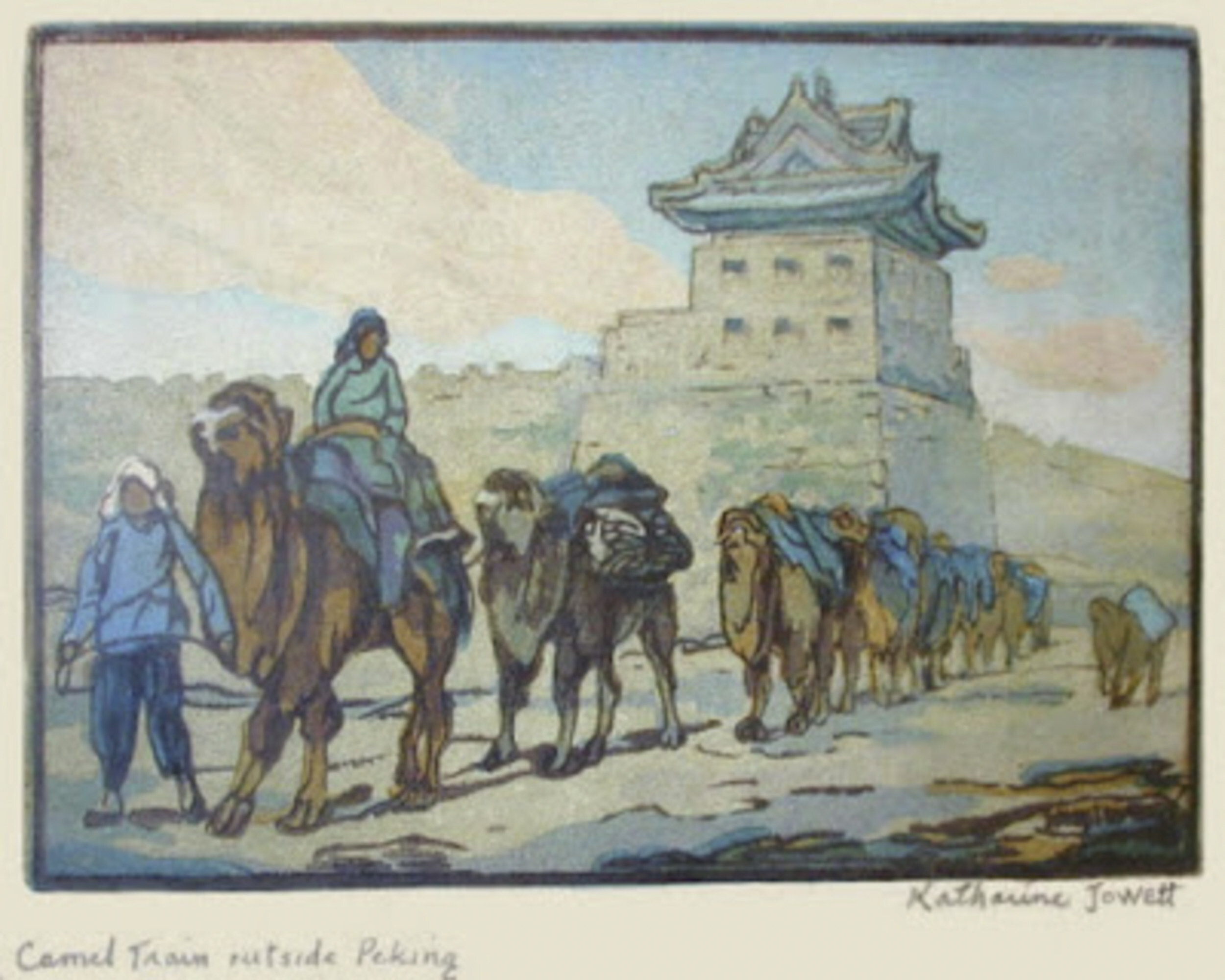

It does seem that Jowett’s work, while capturing the major sites of Beijing – the walls and watchtowers, Forbidden City, pagodas, temples … was aimed at the tourist trade

Lum’s daughter Eleanor, largely raised in China, recalled in her 1950s autobiography that her mother, once divorced, had moved to Beijing with her two children and created an atelier close to the Forbidden City in a hutong courtyard house that had once belonged to a prince – a son of the Daoguang Emperor of the Qing dynasty.

Unlike the other foreign female artists influenced by shin-hanga techniques, Jowett never spent any time studying in Japan. Therefore, it appears most likely that many of the woodblock printing techniques she was to employ in her work were first observed, and perhaps learned, at Lum’s hutong atelier.

Put simply, the artist draws on thin paper that is then glued face-down onto a plank of wood, usually a block of smooth cherry or similar. Oil can be applied to make the image more visible. An incision is made along both sides of each line before the wood is chiselled away, based on the drawing outlines. The block is then inked using a brush and a special tool called a baren presses the paper against the woodblock to apply the ink to the paper.

The later technique of linocut is a variant of woodcut, except a sheet of linoleum, sometimes mounted on a wood block, is used for the relief surface.

Producing art is one thing. Selling it is another. Lum may also have been instrumental in introducing Jowett to the main dealers in the work being produced by herself as well as other foreign women in Beijing at the time, including Hotchkis and Keith. Lum was good friends with Helen Burton, the American proprietor of The Camel’s Bell, a legendary art, curios and crafts emporium in the lobby of the Grand Hôtel de Pékin, on Chang’an Jie.

Burton and Jowett would become close associates, too. Throughout her life Jowett assiduously avoided the press; she appears to have given no interviews or ever had her photograph published. The much more visible and sociable Burton essentially represented her to galleries, dealers and buyers passing through Beijing.

In the 1920s and 30s, the steady stream of international globetrotters on the “Eastern Grand Tour” filed through the doors of The Camel’s Bell where Jowett’s work was prominently displayed. Through Burton and her circle of foreign aesthetes, art lovers and bohemians, Jowett also got to know the owners of many of the various art and curio stores that clustered in the lobby of Peking’s other luxury hotel in the exclusive Legation Quarter, the Grand Hôtel des Wagons-Lits.

It is not that Jowett wasn’t sought-after by collectors of the day, but that they collected Japanese art rather than Chinese. They did, however, appreciate her shin-hanga influences. According to the provenance notes accompanying several Jowett works to come up at auction, Muller, a prolific collector of Japanese art, bought a number of woodcut prints from Jowett when he passed through Beijing on a collecting tour in 1940.

Muller’s well-schooled eye fell on Jowett’s colour woodcut portraits of the Temple of Heaven and the Qianmen Gate, and he snapped them up, and others, for shipment back to the United States. He later sold several at auction with the rest becoming part of his collection now housed at the Smithsonian in Washington.

However, it does seem that Jowett’s work, while capturing the major sites of Beijing – the walls and watchtowers, Forbidden City, pagodas, temples; as well as its peaceful hutong alleyways and nighttime streets lit by fish-skin lamps and paper lanterns – was aimed at the tourist trade.

It is clear that Hyde and Miller’s work displayed stronger traits of Japonisme than that of Jowett. And even though Lum was working from her atelier in Beijing, much of her later work was more art nouveau, intentionally “beautifying” scenes to a greater extent than Jowett.

Hotchkis’ China works were almost exclusively oils and watercolours. Similarly so for Keith, whose largely portrait prints, according to scholar and Chinese art specialist Lisa Claypool, were in the vein of the Chinese painted-likeness tradition xingle tu or “pleasure portraits”, first pioneered during the Southern Qi dynasty (AD479-502).

The full volume of Jowett’s oeuvre remains unclear. There is no definitive catalogue of her work. But tallying up what is in museums, works from private collections detailed on the internet, specialist shin-hanga-related books, with the Jowett works auctioned over the past five decades, shows that at least several dozen woodblock prints, additional linocuts and many oil paintings exist.

She produced scenes to exhibit and some to sell, in numbered editions of 100 or 200 typically, as well as commissions for individual customers and publications – most of which went to private collections.

Yet, as far as can be told Jowett was not attempting to completely support herself with her art and seems to have consciously stayed out of the limelight. Hardy remained the head of Asiatic Petroleum Company in Beijing, as well as serving on the board of the British Chamber of Commerce and the China International Famine Relief Commission, and being active in the Rotary Club.

Their life was pleasant, well-heeled, with a busy schedule of social and business engagements. According to a visiting journalist from the Chicago Tribune they became good friends with a neighbour, George Kin Leung, a Chinese-American from Atlantic City, New Jersey, and an expert on Chinese theatre.

He lived in the beautiful Pan-mou yuan (Half Acre Garden), a Ming-era home with extensive grounds where he organised plays and operas, including appearances by his friend, Peking opera legend Mei Lanfang.

There were tense times, too. In 1930, the Jowetts’ oldest son, Christopher, at 18, was returning from school in Britain on the Trans-Siberian Express. He was to spend some time in Beijing with his parents before starting at Oxford University. Somewhere around Chita, a stop about 900 miles east of the last major city, Irkutsk, his passport was stolen by pickpockets.

Unable to show any identification Christopher was arrested by Soviet authorities. The British newspapers sniffed a good story – the right-leaning Daily Telegraph and the left-leaning Daily Herald both splashed Christopher’s arrest on their front pages and demanded action.

Consequently, hurried communication ensued between the British embassy in Moscow, the consulate in Beijing, and the Foreign Office in London. It helped that Hardy was such a prominent figure in China and that he was a cousin of Fred Jowett, the Labour Party MP for Bradford East, who pulled a few strings.

Christopher was eventually issued replacement documents, released and put on the next train to Beijing. Still, he had spent just over a fortnight in a Soviet jail he described as “filthy”, which had understandably worried his mother considerably.

Throughout the early 1930s Jowett was at her productive peak. Her work clearly indicates that she spent significant time outdoors, sketching and painting Beijing’s sights. But history was closing in.

Hardy had retired in 1933, but the couple had opted to stay in Beijing rather than returning home to Britain. It was to be a short retirement; Hardy died in 1936. In his obituary, The Peiping Chronicle described him as “versatile, genial, and always ready to be helpful, he leaves the Peiping district poorer for his passing”.

Despite being widowed at just 53, and her two sons being in Britain, Jowett chose once again to stay in Beijing. She also didn’t leave after the Japanese invaded and occupied the city in the summer of 1937.

As with other remaining Allied nationals Jowett was eventually interned by the Japanese in 1943 at the Weihsien (Weixian) Civilian Internment Camp in Shandong. During World War II, Weihsien was home to many amateur artists who produced a large number of sketches and oil-painted images of the camp’s daily life.

According to other camp inmates, Jowett became a keen gardener, creating flower beds to brighten up the barracks and involving the camp’s children by planting watermelons, beans, radishes and lettuce.

Jowett was released upon Weihsien’s liberation, in 1945. She returned to England to live in Okehampton, back in Devon, where her younger son, Edward, practised medicine.

Katharine Jowett continued to paint local scenes, unrecognised and unknown for her Asian exploits and adventures, until her death, in 1972, aged 89.