Mainland China not the only option for Hong Kong’s independent filmmakers when it comes to co-productions

- A milestone Hong Kong-Japanese co-production – The Murders of Oiso – shows why the city’s independent directors should be seeking partnerships beyond the border

- Previous collaborations with the mainland haven’t always met with success

The Murders of Oiso is a modest movie about modest lives. Revolving around four young small-town Japanese men trying to find meaning in their mundane existence, the delicately crafted drama is driven by subtle stylistic gestures. But Takuya Misawa’s second feature – coming five years after the 32-year-old director’s critically acclaimed debut Chigasaki Story – has received scant attention at home, with the Japanese press largely overlooking its premiere at last month’s Busan International Film Festival, in South Korea.

While Misawa’s compatriots might have dismissed The Murders of Oiso as yet another small-budget production, the movie is a milestone for Hong Kong. It marks a rare foray for the city’s non-mainstream filmmakers into the world of international co-productions.

Tonikaku Pictures, the company behind the movie, was founded by Hong Kong indie filmmaker Wong Fei-pang, who is known locally for his directorial debut, An Odd Fish (2014), and Season of the End, his contribution to the 2015 omnibus film Ten Years . Wong and Misawa met at the Busan film festival in 2015 and started planning a collaboration.

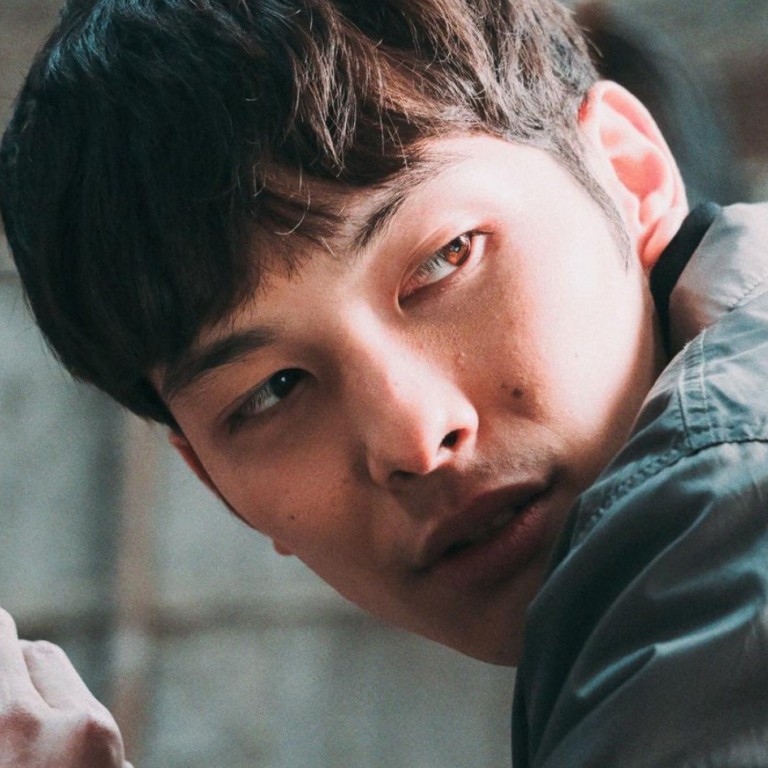

Having secured funding from the festival’s Asian Cinema Fund, the pair began to gather a crew for their project. The Hong Kong component is more than nominal: on screen, actor Lo Chun-yip plays a bullied young man, whose final act in the film proves to be a coup de grâce for the fate of the four lead characters; off screen, Wong was joined by a Hong Kong crew that included cinematographer Timliu Liu. Speaking after a screening of Murders in Hong Kong, Misawa admits his movie looks and sounds markedly different from other Japanese films of this kind.

Wong says Murders was the result of an effort to establish connections between local filmmakers and kindred spirits across Asia and beyond. Wong and Misawa pitched their idea far and wide, including at festivals such as Belfort, in France.

“It’s proof that there’s more than this one place we can turn to if we think of doing co-productions,” Wong told me after the screening.

The “one place” he is referring to is, of course, mainland China, with its film industry flush with investors but also hemmed in by a rigorous censorship system.

At the same time, Peter Chan Ho-sun was nurturing his own multinational dreams in Hong Kong as he launched Applause Pictures. Aimed at establishing a pan-Asian network of filmmakers, the company produced movies such as South Korean director Hur Jin-ho’s One Fine Spring Day (2001) and Thai filmmaker Nonzee Nimibutr’s Jan Dara (2001).

Chan’s ambitions faded as he looked north for investment and audiences, his first step being Perhaps Love (2005), a musical boasting a multinational cast (mainland China’s Zhou Xun, Taiwanese-Japanese Takeshi Kaneshiro, Hong Kong’s Jacky Cheung Hok-yau and South Korea’s Ji Jin-hee) but filmed in Beijing and Shanghai. That would prove to be one of his last productions under the Applause banner and a sad end to what could have been a fascinating international adventure for both himself and Hong Kong cinema.

A mainstream filmmaker through and through, Chan would have probably found it hard to believe his unfinished task would eventually be taken up by the city’s young indie rebels.

Then again, it’s only by a broadening of vision and networks that Hong Kong filmmakers – and Hong Kong in general – can move forward: a small film it might be, but The Murders of Oiso – and the roles played by its Hong Kong crew – might signal something new and crucial for the future of the city.