Scandal surrounding Chinese artist Ye Yongqing, accused of plagiarism, has left collectors fuming

The renowned painter, who has exhibited all over the world, denies that he has copied Belgian artist Christian Silvain, and is seeking legal advice

Last month, Belgian artist Christian Silvain accused Chinese painter Ye Yongqing of having plagiarised his work since the 1980s, with some of the “copies” selling for a lot more than the originals did. By the first week of March, the claim – originally made on Belgian television – had gone viral on WeChat, China’s popular social-media platform. The online community seems to be on the 69-year-old Silvain’s side. Ye himself acknowledges Silvain as a major artistic influence but denies that this amounts to plagiarism.

“You think that I am a liar, and I have amassed great wealth by plagiarising your works, and that I am supported by many people with a vested interest. However, none of this is true,” Ye said in an online statement on March 18, adding that he was seeking legal advice.

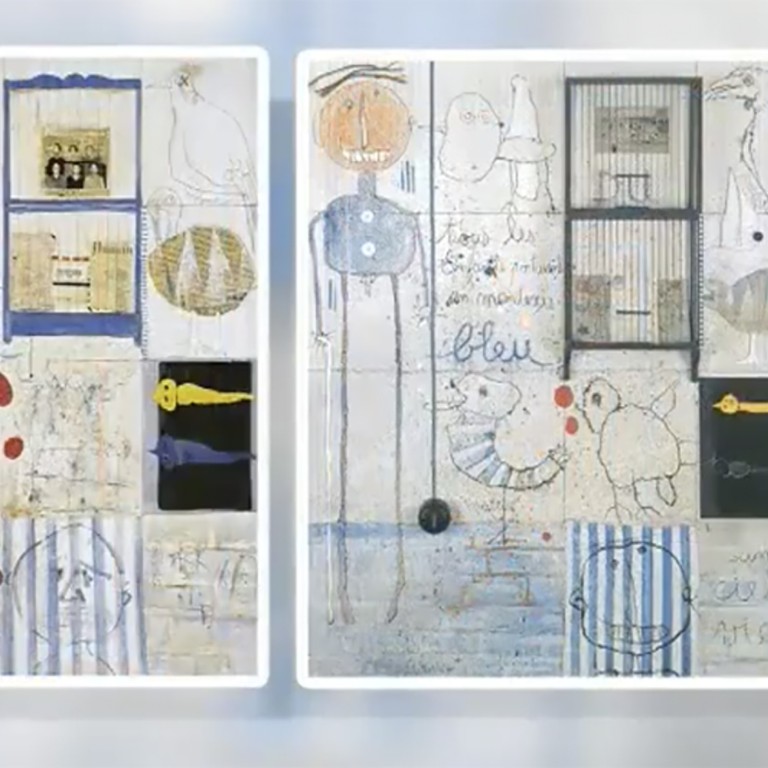

Place the two artists’ grid paintings side by side and it is a case of “spot the difference”. The childlike illustrations, symbols and colour palette are almost identical.

If [Ye] doesn’t apologise, I plan to invite the Belgian artist to show at the museum, and then label all the Ye paintings as ‘copies’ from now on

In Ye’s paintings, you can find Silvain’s arrangement of original symbols in a grid-like design, such as strange, black birds and the silhouette of a tree, faithfully replicated. Sure, there are differences here and there. But it is hard to believe that Ye came up with all this “Out of Nothing”, as his solo exhibition at Shanghai’s Yuz Museum last year was called.

Ye, born in 1958, was part of China’s “85 New Wave” group of artists who embraced the avant garde before the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown. He became a professor at his alma mater, the Chongqing-based Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, and has exhibited all over the world since the 1990s – around the time when he started the grid paintings.

The institute issued a statement on March 7 saying Ye had retired but promised it would investigate.

“If [Ye] doesn’t apologise, I plan to invite the Belgian artist to show at the museum, and then label all the Ye paintings as ‘copies’ from now on,” Liu says, adding that art critics who helped promote the Chinese painter over the years are now falling over each other to apologise. “They are behaving as if they have swallowed a fly.”

In a statement dated March 22, the Zhi Art Museum, in Chengdu, said that it has cancelled an order for new works by Ye and is demanding a refund. And Sotheby’s has pulled one of the artist’s works from its upcoming Contemporary Art auction in Hong Kong.

Equally unhappy are some former clients of Hong Kong-based Art Futures Group. Established in 2010, the company sells contemporary Chinese art to investors and then leases it to third parties, such as corporate offices and hotels, in order to generate a guaranteed annual yield of 6 per cent for the owners. The company told me in 2013 that clients should earn even more than that because prices for Chinese art were going up and up. With such good returns, it really didn’t matter if investors disliked the art, its then managing director Jon Reade said.

It turns out it did matter.

Bloomberg recently interviewed several individuals who said on the record that they regretted buying contemporary Chinese art from Art Futures Group and that they were unhappy that the company did not renew their rental agreement after two years. They also claimed that they were having trouble selling the art because the secondary market valued the pieces significantly lower than the figure they had paid the company.

In an email reply to The Collector, Jeremy Kasler, chief executive of Art Futures Group, denies that the company gives clients the impression it is obliged to lease their art beyond two years. He also denies that Art Futures Group has sold them works of poor quality, saying they were vetted by an independent valuation company, Roma Group, and public auction records show there is a healthy demand for the artists named in the Bloomberg report.

Whatever the rights and wrongs, this episode highlights the fact that way too many people are seduced by the glamour of art investment into making snap decisions.

So how do you choose the right artist at the right price? That is a question Western galleries that are new to the region are grappling with, too.

German art dealer David Zwirner, who opened a branch of his eponymous gallery in Hong Kong last year, has announced that it is now representing Liu Ye. The Beijing-based painter is the only Chinese among 64 artists the gallery represents. (It used to represent Yan Peiming.)

Why Liu? “Because he can look at our existing list of figurative artists eye to eye,” Zwirner says, referring to people such as Neo Rauch, who has a show at the Hong Kong gallery this week, and Luc Tuymans, who will be showing later this year.

But most importantly, Zwirner’s decision is based on how Liu’s art – both alien and familiar – has an effect on him personally.

“We were both born in 1964 but we come from totally different backgrounds. I had a fun time growing up in super-liberal Germany and he was in the Cultural Revolution,” Zwirner says. “There’s a spiritual, quiet quality that I characterise as Asian in his work. But he also has a powerful dialogue with the Western canon. And since he lived for a while in Germany and speaks German, we can communicate well with each other.

“To me, Liu has produced some of the most powerful political art I’ve seen and I believe his best is ahead of him.”