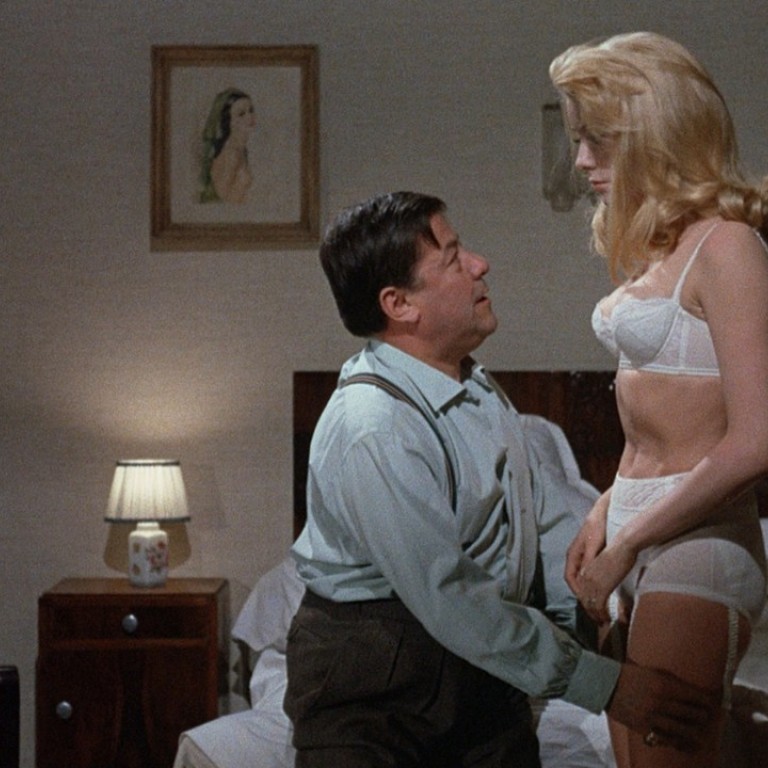

Catherine Deneuve plays bored housewife-turned-prostitute in Luis Bunuel’s erotic masterpiece Belle de Jour (1967)

French actress delivers a great performance playing Séverine, a tai-tai with masochistic sexual fantasies who takes a job at a brothel, where a vicious young client becomes obsessed about her

Spanish director Luis Buñuel’s best-known movie, Belle de Jour (1967), is a provocative mixture of eroticism, surrealism, social commentary and experimental filmmaking. The narrative is seemingly straightforward: a bored, wealthy French housewife (played by Catherine Deneuve) seeks excitement by working as a prostitute in a brothel.

But Buñuel, who resisted straightforward psychological interpretations of his characters’ actions, voices it in a surrealist world set between dreamlike fantasies and reality, and the viewer is never sure whether things are happening in the exterior world or in the mind of the housewife. Buñuel also delivers his customary excoriation of middle-class life, which he felt was vacuous, self-serving and impotent.

The film is based on Joseph Kessel’s 1928 novel of the same name.

Séverine (Deneuve) is a tai-tai who lives with her thoughtful but dull husband Pierre (Jean Sorel). Séverine has erotic masochistic fantasies and, after being given an address by a lascivious male friend, takes a job at an upscale brothel. Her attitude to her work there is ambivalent: a mixture of enjoyment, disgust and curiosity. Her adventure takes a dangerous turn when a vicious young client becomes obsessed with her.

Buñuel did not despise his actors like Alfred Hitchcock did, but he did not engage with them on the set either, simply telling them what physical actions to perform, without discussing their motivations or any internal processes. This works well in Belle de Jour, where Deneuve becomes a tabula rasa onto which viewers can project their own desires. The actress has said in interviews that she felt she was not treated well by Buñuel, but admits that his methods did elicit a great performance from her.

Buñuel always refused to talk about the psychology of his characters – or the meaning of his films – but that doesn’t mean some kind of psychological reading is not possible. Indeed, Buñuel reportedly talked to psychologists about patients who exhibited masochistic tendencies when he was writing

the script.

What the director objected to was the rational approach of Freudian psychoanalysis, which was in its heyday during the 1960s. Buñuel’s own view of the mind – that it is driven by deep irrational forces that are unknown to us, and maybe even unknowable to us – is closer to modern psychological theory, and even neuroscience. We cannot understand why Séverine does what she does, because she cannot understand it herself.

As a surrealist, Buñuel would claim the shifting dreamworld that Séverine inhabits is, in fact, the totality of our daily reality, even though we are not aware of it. The film’s strange ending makes this point perfectly.