Why tales of self-made tycoons owe more to myth than reality, in Hong Kong and elsewhere

Rags-to-riches stories are ten a penny, but the finer points of how billionaires reach their fortunes are often overlooked or even omitted

Among Hong Kong’s endlessly repeated, clichéd tropes is that of the self-made local billionaire. In a society that – until recently, at least – worshipped the very wealthy for no reason other than their possession of stupendous amounts of money, this myth had resonance. The fact that Hong Kong’s parasitic, rent-hungry elites are now widely despised is due to greater public awareness of how these people “achieved” such massive fortunes in the course of a single lifetime.

Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw famously remarked that the more he saw of the very wealthy and their ways, the more he understood why the guillotine was invented. This sharp observation neatly conveys sentiments that grow stronger in contemporary Hong Kong as social inequality balloons, youth opportunities diminish and official venality, incompetence and arrogance become more pronounced.

The more I see of the moneyed classes, the more I understand the guillotine

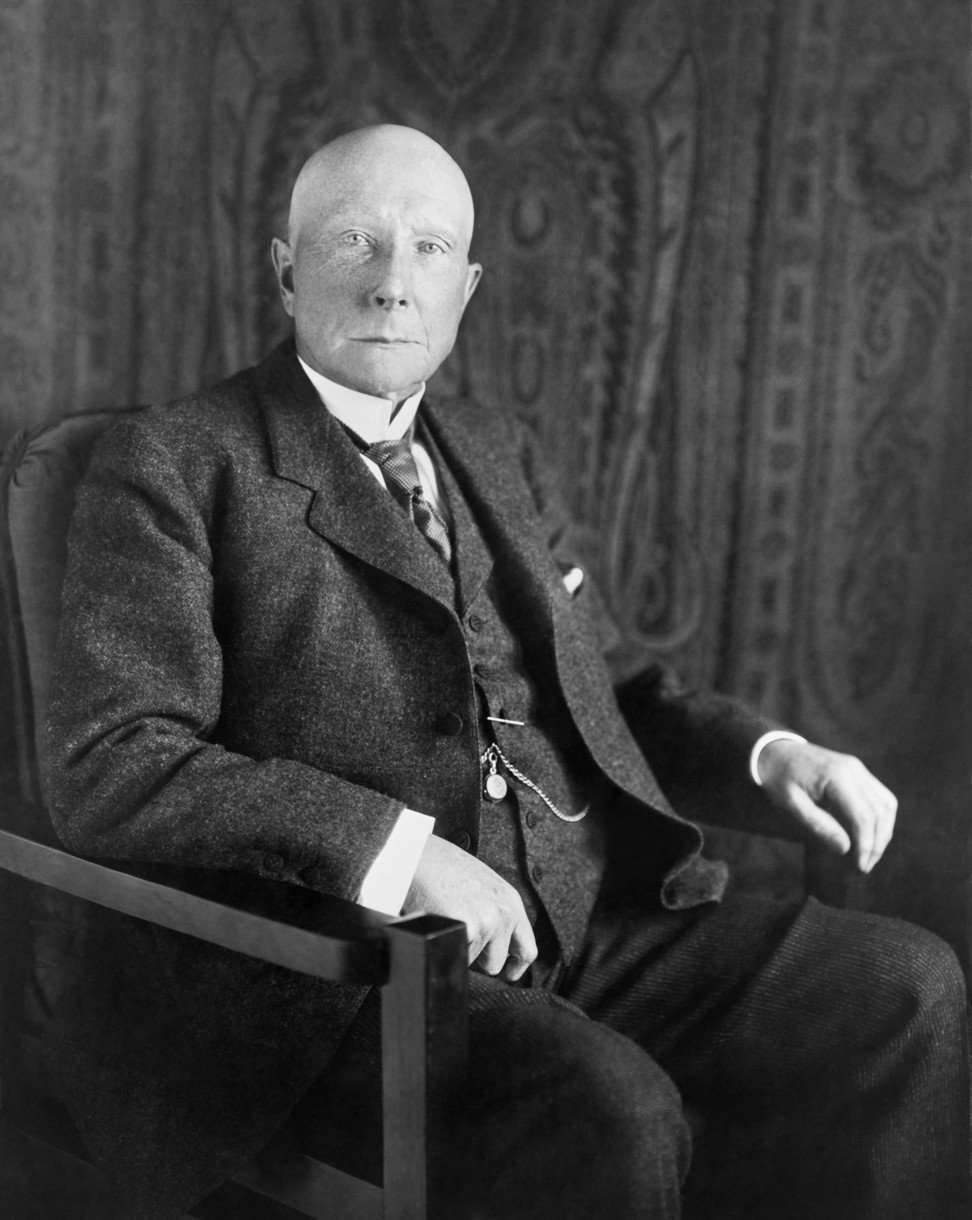

From the first generation of oligarchic property magnates on, the myth maintains how the hard-working rickshaw puller (or tailor, or goldsmith or other position of humble origin suggested in a billionaire’s personal foundation legend) started out with almost nothing. Through sheer determination and entrepreneurial ability, he (it’s always a he in this culture) surmounted enormous odds – perhaps with a little help from ancestors and feng shui – to hit the big time and stay there. But, as with all creation myths, the facts are usually far more prosaic.

Marrying into money and prestige for a kick-start in life is usually not part of the Hong Kong tycoon’s publicly traded backstory. Strenuous efforts are made to ensure that such details, and other inconvenient, potentially embarrassing, pre-fame facts, are neatly airbrushed out of history. Personal or professional dirt gets swept under the carpet at considerable effort and expense, and stays there for at least as long as the tycoon in question remains sentient, alert to actual or perceived slights, and potentially litigious.

Like all comforting Hong Kong myths, that of the local self-made billionaire continues to be repeated. For certain vested interests, maintaining the illusion that Hong Kong remains – despite ample evidence to the contrary – a society where one can start from nothing and rise to the top is vital.

Another myth relates to the independence of the local media and public relations industries. Hong Kong is a small pond, and repeated access to these “newsworthy” people is usually dependent on their own heavily edited version of themselves being given adequate, regular, uncritical airtime. In consequence, certain fairy stories develop a patina of truth from public repetition over many years.