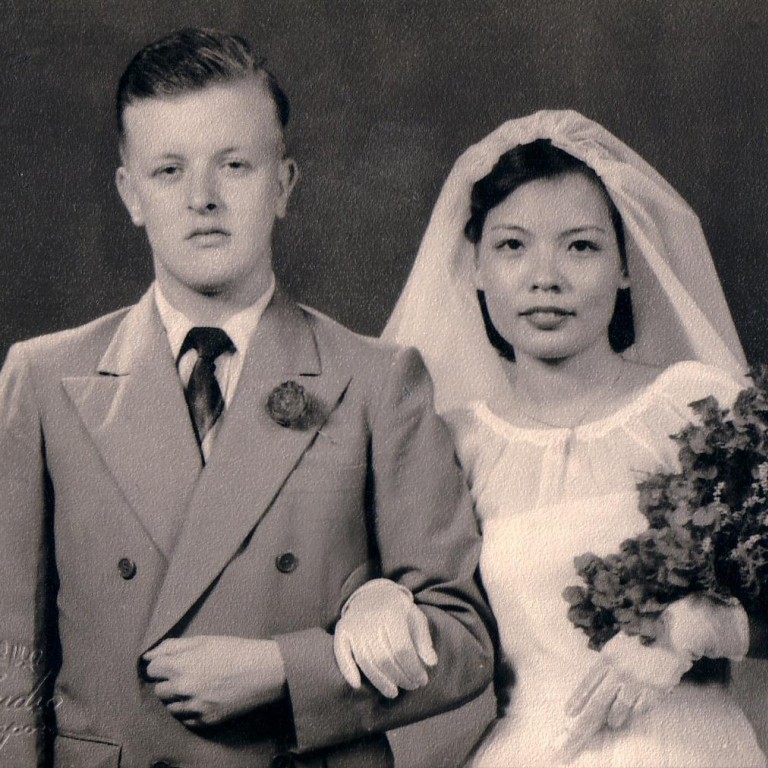

When Hong Kong expats were found ‘suitable’ wives by bosses and their spouses

Right up to the 1950s, men arriving in Hong Kong to join companies were not expected - and in some cases were forbidden - to marry for the first 10 years, whereupon their employers would choose a mate for them, Jason Wordie writes

Job-hopping and career changes are the modern norm; spending one’s entire working life with a single employer is now a relic from another era. Likewise, the thought that a work superior could have the final say in an individual’s choice of partner, and that company policy might dictate when – and if – one might marry, seems incredible.

But not that long ago, senior executives intimately controlled their employees’ love lives for reasons that – while certainly intrusive, and unacceptable from a contemporary perspective – were then considered reasonable from a business standpoint.

Well into the 1950s, young men coming out to the Far East to join banks, shipping lines, plantation companies or trading firms did not receive paid home leave until the end of their first five years. Trainees were expected to “learn the ropes” and that meant putting in long hours in close contact with other juniors, with no time for personal distractions beyond sports. Overnight regional postings were the norm. Nothing in this lifestyle was conducive to long-term success for young relationships forged in strange, exotic places.

Some employment contracts explicitly stated (though the terms varied from company to company) that an individual should not marry until the end of their second contract. By that point, an up-and-coming executive would have accumulated about a decade of experience, and their pay and bonuses would be sufficient to keep a wife in a socially accepted manner. Except for charitable or voluntary work, European executives’ wives were not expected to undertake paid employment after marriage, and in any case, frequent regional postings ensured that their meaningful, long-term career opportunities were limited.

Permission to marry had to be applied for, and prospective wives were vetted by senior management – and their wives – for “suitability”. Similar systems operated in the armed services.

The criteria for an individual’s suitability was surprisingly objective. Being able to “fit in”, and get on with the life she encountered in small, remote places with limited social opportunities, without undue complaint, was vital.

To ensure successful matches, the pool of potential marriage partners was frequently drawn from the daughters of families already resident in the Far East, as they knew what to expect. Sisters of men who had come out to the region for an extended visit, with the unstated aim of finding a match, were also popular choices.

As these women understood what they were getting into, they were unlikely to seek solace from boredom, frustration and loneliness either in the gin bottle by late morning or in the arms of the nearest passing bachelor. In spite of these precautions, not everyone made a success of their circumstances, but corporate marital vetting ensured the odds in favour were significantly improved.

Successful Far Eastern careers – and eventual pensions – closely depended on long-term job stability. Unlike today, alternative employment opportunities in a similar field in the same place were extremely limited. Job skills derived from knowledge of Far Eastern conditions were not always transferable, should an employee decide to return to their home country. Divorce wasn’t an option unless adultery was involved. If an executive eventually lost his job – especially if this was due to tensions caused by their personal activities – dismissal really was a catastrophe.

For more on Hong Kong history and heritage, go to scmp.com/topics/old-hong-kong