Hong Kong toy tycoon’s success story begins with the yellow rubber duck

Toy tycoon Lam Leung-tim tells Oliver Chou about surviving the Japanese occupation, his loyalty to China and building perhaps the most playful business empire in Hong Kong.

Long before the giant, inflatable rubber duck floated into Victoria Harbour, in 2013, the original, miniature version – just as yellow and buoyant – arrived with a quack in Hong Kong.

“My duck represents a typical Lion Rock story of how we built a global empire from nothing,” says Lam Leung-tim, now aged 91, about his 1948 pet project.

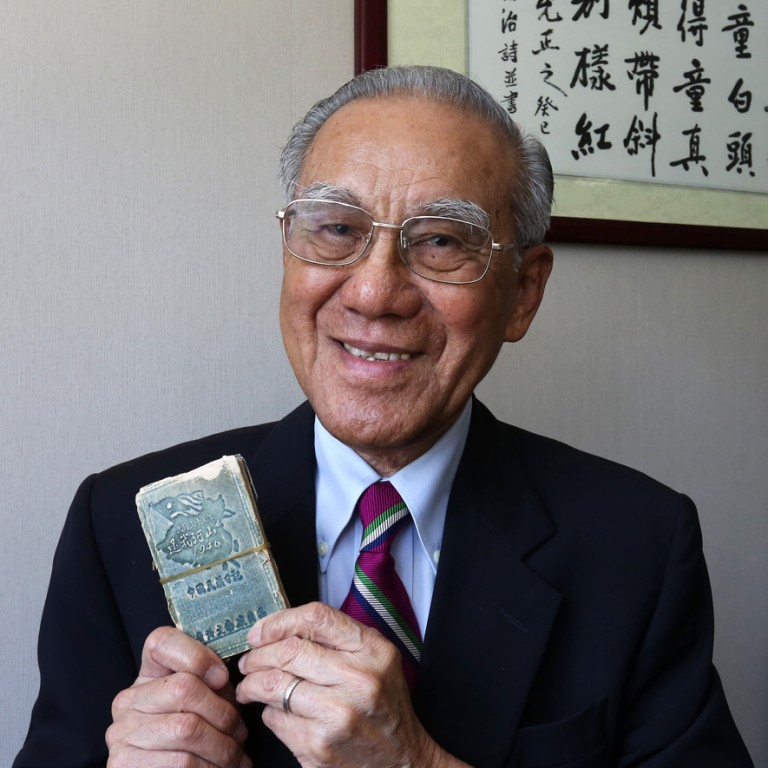

Known as LT Lam in industry circles, the nonagenarian is the sole surviving toy-industry pioneer from the city’s post-war era. With numerous accolades under his belt, the latest being the Industrialist of the Year Award 2015 (to be presented by the Federation of Hong Kong Industries on Tuesday), Lam is proud to see the third generation of his family join his business, Forward Winsome Industries, the history of which can be traced back to 1947.

The father of Jeffrey Lam Kin-fung – the member of the Executive and Legislative councils who infamously scuppered electoral reform in June by leading the walkout of pro-Beijing legislators ahead of the vote – he may be, but Lam Snr is also known as the “Father of Transformers in China”, after the robotic toy he introduced to the nation, and, of course, for that little duck he brought into existence more than six decades ago.

“MY FATHER WAS THE SECOND child of 12 in Nanhai, near Foshan, in Guangdong province, and came to Hong Kong in 1905,” Lam begins, speaking in a conference room surrounded by toys at Chai Wan’s Eltee Building – which is named after his initials. “After four years he returned to get married and then brought his newlywed to Hong Kong, where he worked as a live-in cook.”

When Lam was born, on March 30, 1924, at a hospital in Wan Chai, his father was a chef at the residence of the general manager of American Express: the mansion at 14 Old Peak Road, in Mid-Levels.

“I got my first toy there, when I was four, and it was a ping-pong ball. But I accidentally sat on it and crushed it; I cried bitterly,” Lam laughs.

In 1931, his mother took the then seven-year-old Lam back to Nanhai. For the next four years, he was strictly disciplined by his mother and received a traditional education from his maternal grandfather, who taught the classics at his school.

“When mother read to me from the newspapers my father sent from Hong Kong about the Japanese invasion of northeast China [in 1931], I asked how Japan, a smaller country, could attack China, a much bigger country. Then mother said one method they had was to sell toys to get money for guns and bullets. That planted a seed in me to make toys for a greater cause,” he says.

Before that seed had a chance to grow, the war had made its way to Hong Kong, and Lam was in the city to see the first Japanese aircraft above Victoria Harbour.

“I returned to Hong Kong in 1936 and attended Wah Yan College at the time when Japan attacked us. It was December 8 [1941], a Monday, the first day of exams, and I was fully prepared for it. Father made breakfast for me; minced beef on steamed rice. We were then on the top floor of a godown of Jardine Matheson – where Sogo now is, in Causeway Bay – which was a [dormitory] for the young managers, and father worked there as a chef. At 8am I was eating and caught sight of incoming Japanese airplanes bombing the harbour. I was so frightened that the bowl fell out of my hands. It was the last day of my student life; I never returned to school again,” he says.

The managers fled but father and son stayed put at the godown.

“On December 24, around 4pm, father asked me to go home first and said he would join me after cleaning up the office. Those were the last words I heard from him,” says Lam, his face turning grim.

Lam had a long wait at their small rented room on Haven Street, in Causeway Bay.

“Mother sent me to look for father after dark. When I got to the street, I saw father’s body on the ground, with no sign of life. The Japanese sentry on the street corner signalled me to go to him. I didn’t understand what he said, but from his sign language, I figured out that father had not stopped as instructed when crossing the street and was stabbed to death by a bayonet. He was just 48,” says Lam.

His father had been deaf ever since a bomb had fallen near him while he was running errands in Central, says Lam.

Shortly after the burial of his father at Mount Caroline Cemetery, near the present Hong Kong Stadium, in Happy Valley, Lam joined a funeral team removing dead bodies from the streets of Causeway Bay.

“We picked up 30 to 40 bodies of young Canadian soldiers from the 1,100 who took part in the defence of Hong Kong. The fight started from North Point and was the deadliest on Yee Wo Street before surrender was called at Percival Street,” he says.

The Japanese occupation proved too much for the bereaved mother and son. In March 1942 they made their way back to Nanhai. For the next three years, the former high-flying Wah Yan student was a peasant: “My back faces the sun and my face the earth,” he quotes an old saying about working in the fields.

On his mother’s orders, Lam married just before the war ended. His bride, Yuki Leung Yu-ng, belonged to a well-off family in Nanhai. The deteriorating economy in the run-up to the civil war plagued the newlyweds, however, and Lam decided to return to Hong Kong alone. The family scraped together HK$100 for his move.

After working briefly in Sheung Shui as a labourer, Lam rejoined the funeral team in Causeway Bay, making HK$2 at each service. Two months later, the principal of Wah Yan College, his alma mater, found two job offers for him, as an assistant at Shek Kong airfield for HK$100 a month and as a teller at the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank for HK$120.

He turned down both.

“Shek Kong was too far away and I couldn’t see any future at a bank which hired a lot of Portuguese from St Joseph’s College. I would play only a second-fiddle role as I was no match for their fluent English,” he laughs.

Instead, the 22-year old became a salesman for a newspaper vendor in Central, for a monthly salary of HK$60.

“I was the only staff under the boss so I was in full charge of dealing with customers, including the elites in Central, such as the honourable Jehangir Ruttonjee himself, who placed his order for [American magazine] The Saturday Evening Post with me. That helped me build up my contact list. The small commission charge accorded to me amounted to a few thousand dollars in my first year, and that became my first bucket of gold,” he says, showing me the notebook he used in 1946.

The biggest advantage of the newspaper job, he says, was access to the latest international magazines, such as Life and Look, which became his source of information about the outside world. He was particularly struck by the colourful plastic products he saw advertised inside.

His next opportunity came in 1947, when, through a connection of his mother’s, he joined an industrial materials company.

“I advised Norman Young, boss of Yuen Hing Hong, to be an agent for plastic materials from which to make simple products, such as the stands for restaurant menus. With his approval, Winsome Plastic Works was opened at 93 Hennessy Road,” he recalls.

Lam recruited a former dockyard mechanic to build extrusion machines he had designed. Their initial success reignited his childhood fascination with toys.

“My ideal toys are durable and colourful; attractive to children. I studied Japanese toy catalogues and there were chickens, fish, dolls, etc. Then I thought a floating duck would be fun to play with, even in the bathtub. A rubber duck was different from most Japanese toys, which were made of cellulose that was inflammable and breakable. As for the colour, there is an old Chinese saying, yellow goose and green duck. Well, I guess I made a pleasant mistake,” he laughs.

As far as Lam is concerned, his 1948 rubber duck, which he now calls the “Lamon Tea duck”, was Hong Kong’s first plastic toy. It came into being almost a year ahead of Peter Ganine’s floating duck – the model for the giant inflatable version by Dutch artist Florentijn Hofman that visited Hong Kong – which the Russian-American sculptor patented in the United States in 1949.

“Plastic industries in Hong Kong at the time manufactured mostly daily utility products, such as hangers, bowls, plates and combs. Manufacturers from Shanghai were relocating to the territory with capital and machinery. If they were born with a golden spoon in their mouth, what we locals got was just rusted metal,” he says.

Armed with new plastic products in 1948, Lam and others invested in a factory in Guangzhou, a controversial move given that many entrepreneurs were fleeing the country as the civil war began to turn in the communists’ favour.

“You may call me naive, but I truly believed in building the country with whatever means I had. I can’t forget those scenes in the wet market my mother took me to in my younger days, when I saw Indian patrols that the British had brought in run after Hongkongers with their batons. How could we be worse than those Indians who had lost their country to the British? That feeling was and still is very strong in me,” he says.

Lam put his first “bucket of gold” into the Guangzhou venture and visited yearly with Jeffrey, then a toddler, until the plant was nationalised, in 1953.

Lam turned his attention back to Hong Kong and founded Advance Plastics Factory in Tai Kok Tsui, the first plant he fully owned. Its first product was a soap box decorated with a crown, to commemorate the Queen of England’s accession to the throne, in 1952.

“My boss at Winsome was not happy that I opened my own factory and asked me to give it up by offering me 25 per cent of Winsome’s shares, and I agreed,” he says.

But before long, Lam was itching to go it alone, again. In 1955, he founded Forward Products and, in 1957, Alice Doll Fashions, with his wife.

“I saw a doll in the corner of a shop window display in Central and the fine craft attracted me. So I bought the 20 or so dolls they had. It turned out to be the German Lilli doll and I asked my wife to make clothes for it. She was an excellent craftswoman and produced exquisite fashions for the doll on a Singer sewing machine we were paying for by instalment.”

Lam Lai-yee, LT’s younger sister, also worked for Alice Doll Fashions.

“Over time, the doll became very popular and we made a lot of money. It created a vogue that brought about the Barbie doll, in 1959,” he claims.

In 1960, Lam was offered a deal: Winsome Plastic Works would merge with Forward Products to form Forward Winsome Industries. Two years later he would be the sole owner of the new company.

“My partner and former boss [Young] offered me his 50 per cent share at HK$250,000, but I did not have it. Then one day a friend took me for coffee in Central and gave me a cheque for that amount. Unconditional and interest-free, his offer surprised me,” says Lam.

The man was repaying an old favour.

“I had put forward an idea to him of a plastic product, and from that he had made a fortune. Eleven years later, he came back to me with the surprise offer, which I took with gratitude. I repaid him in four years,” Lam says.

Shortly after Lam became sole proprietor, a representative of Hassenfeld Brothers, the company that became toy giant Hasbro, came to Hong Kong looking for a partner to work on a new project: G.I. Joe.

“I turned him down because I wasn’t ready for such a large contract. Instead I referred him to the Hong Kong Industrial Company, which returned the favour with a contract for the uniform for Alice Doll Fashions,” he recalls.

Lam’s honesty impressed Alan Hassenfeld, one of Hasbro’s owners and a friend to this day.

The turbulent 1960s was a time of challenge and opportunity.

“A few loyal workers came to me one day and asked for half a day off to take part in a parade in support of the protesters against the colonial government,” says Lam, of the lead-up to the 1967 riots in Hong Kong, which pitted workers against capitalists. “So I let them take leave but told them to stay away from trouble and violence.”

During this period, Lam turned economic uncertainty to his advantage.

“In 1968, I won the bid at just HK$68 per square foot and built this Eltee Building. In just three years, the value went up to HK$3,000 per square foot,” he says, with a board smile.

Unlike those who have left due to recurring insecurity, Lam has stayed true to his country: “I built three factories in Taiwan in 1969 because it’s part of China. In 1976, I visited the mainland for the first time since I departed my Guangzhou factory in 1953. The conditions in the factories I saw was so poor that I felt I should help.”

In 1979, Lam set up his first factory in Dongguan, with just 25 staff. In 1982, Lam embarked on a project to turn his hometown, Nanhai, into “Toy City”. The number of workers he employed would grow to 20,000, boosted significantly by the Transformers figures (for anyone too young to remember, the Japanese-conceived Autobots and Decepticons existed in toy form long before Michael Bay began making his live-action film series), a worldwide sensation and the first Hong Kong-American joint toy venture.

“It was no easy thing to get Hasbro to agree to invest in China in those days, even when I finally convinced my old friend Alan Hassenfeld – the board members were a different story.

“It was at a function in the [Marco Polo] Hongkong Hotel that I made a presentation to the board members of Hasbro. I got my speech carefully translated by a professor from Cornell University [in New York], of which I have been a patron since the 1970s, mapping out my China vision,” he says.

With the board’s approval, Lam took Transformers to China and, in 1988, the sales were so great they made headlines that drew concern among members of the National People’s Congress. In 1989, Xinhua reported that 20 NPC standing committee members had criticised the toy series for its “violent and ridiculous content”, claiming it had become a financial burden for many families (a whole set cost more than 1,000 yuan).

LAM’S WIFE, YUKI, DIED of a heart attack in her sleep in 1985, a day after his 61st birthday.

“She had not been happy since she lost her mother during the Japanese war and her father during the land reform in communist China,” he says.

Jeffrey, his oldest son and the natural successor to Forward Winsome, of which he is managing director, spends more time as a cabinet and legislative member than at the family business, says Lam.

“I only hope the sacrifice we make in the family is matched by the contribution to the society Jeffrey is making,” he says, perhaps reflecting on that very public blunder his son made in June.

Victor Lam Hoi-cheung, Jeffrey’s only son and a graduate of Cornell University, is now the general manager of Forward Winsome Industries. He will be joined soon by his cousin, Alvin, the youngest son of Jeffrey’s younger brother, Daniel, the managing director of Alice Doll Fashions.

“Poor with dignity and rich with integrity” is a motto Lam, at 91, says he hopes to convey to Hong Kong, especially the younger generation. The best agent for the message is the rubber duck, he says, which he relaunched last year through his newest company, Funderful Creations.

The toy carries a note: “You may wonder why we’re yellow. The reason goes back nearly seven decades. After long, dark years of war, our creator, the 90-year old Mr LT Lam, dreamed of a world filled with colour. Today, we yellow ducks still have important work to do … our hope is that all you children will learn to share, play and live together harmoniously so future generations will continue to enjoy peace, friendship and prosperity.”