Getting a physical in Bangkok: a health check-up that's worth every baht

Physician-phobe Cecilie Gamst Berg casts her fears aside and books in for a 'super-intrusive' check-up at Bangkok's Bumrungrad International Hospital.

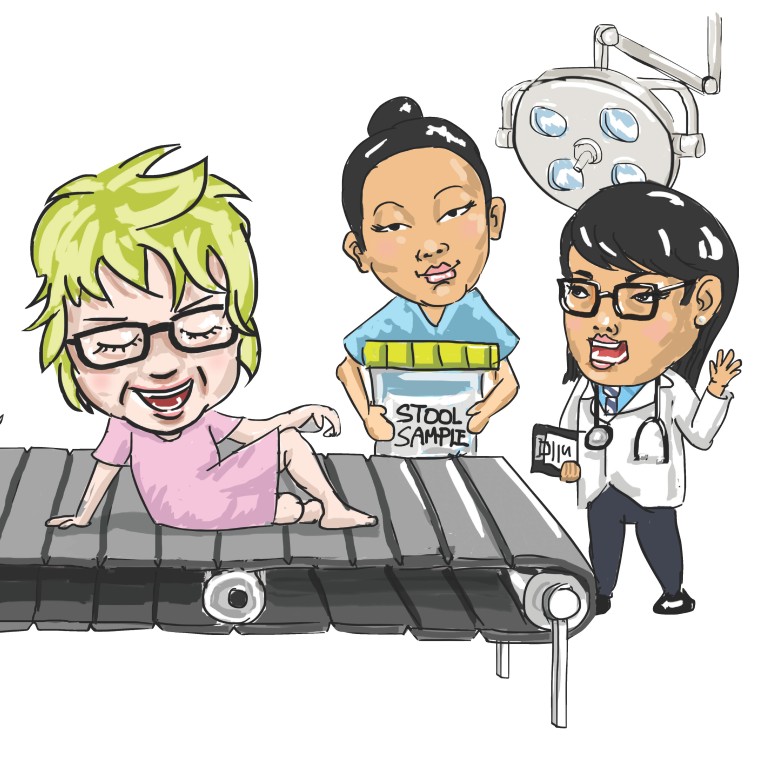

"So, did you manage to drop the kids off at the pool?" my friend Ruth euphemistically asks as we reach the hotel. I mumble a reply in the negative. It has been a rather harrowing day at the Bumrungrad International Hospital, in Bangkok, having our everythings checked.

Ruth and I, initially not very intimate friends, now know more about the other's inner workings than is perhaps strictly necessary. For example, she was able to produce a stool sample ("drop the kids off") during the examination and I was not. I feel like a failure.

The fear of stool-related failure was exactly the kind of thing that had made me put off seeing a doctor for so many years. When it comes to health there are two types of people: those who think ignorance is bliss and that being told they suffer from some kind of condition will immediately make them pop off to the big waiting room in the sky; and those who run to the doctor as soon as they feel an itch in their throat, clogging up emergency wards with imaginary ailments and ruining other people's chances of surviving the next bubonic plague by incessantly popping antibiotics and thus making viruses immune.

I belong firmly in the former camp. I don't have a doctor and I stay away from anything in a white uniform smelling of disinfectant. I had a "physical" about 15 years ago, when I started paying for life insurance (which seems to mean that people I don't even like will get a large sum of money after I die), and found the experience nasty and humiliating. I hadn't seen a doctor since then.

I told myself it was because I hate officious clipboard-nazis shouting out what's wrong with me across a crowded, freezing waiting room, and the brutal bedside manner of Hong Kong doctors (no eye contact, in and out in five seconds flat, big bag of antibiotics no matter what the ailment is). Also, well, I was never sick. But the truth is I was afraid I'd be told something was wrong. A secret smoker, I wanted to kick the habit before some jumped-up pre-pubescent doctor in oversized glasses had the chance to tell me to do so. Also, if I had to have a chest X-ray, I wanted to clean out my lungs first, so they wouldn't look like the "whatever you do, don't buy this product" organs they put on cigarette packets.

And so the years slid by.

Then, in December 2012, I managed to stop smoking quite effortlessly, and with all that free time on my hands I started doing the things I'd been putting off for years. First stop was the dentist and, as I sat there having a huge syringe jammed through my jaw and into my knees, I realised I hadn't had my teeth checked in seven years. Time flies when one is a secret smoker.

Those seven years had been a busy time for my gums; they had gone and created a lovely gingivitis soup of the kind that makes your teeth loosen and fall out. So I had to have four operations, with much cutting of skin and scraping of jawbone. It didn't half set me back a few bob, either. I learned that actions, or rather inactions, have consequences.

Given a family history of health problems, why shouldn't I go and have myself checked out? Because they would touch me with cold metal things and shout out across the waiting room that I had three hours left to live; I just knew it.

Then, one day in December, I was having a glass of health-giving white wine with a friend, Ann, and we started talking about another friend, younger than me, who had died suddenly of cervical cancer. She had never had a pap smear.

"Right, that's it," I said, banging the table with my fist. "I'm going to the damned doctor! But where should I go?"

"Bangkok," Ann said.

The next time I saw Ruth I mentioned it to her, and it turned out she had also been hiding from doctors for years. Now was the time! We booked and paid for everything online before we had time to change our minds.

Ruth and I stumble off the budget airline plane in Bangkok. The flight was super cheap, the hotel even cheaper (deservedly so) and the check-ups will cost half of what they would have in Hong Kong. Why, we are saving money by the minute!

After a night without beer and following the strict rule of no food for nine hours before procedures, I am woken at 5am by that great alarm clock, dread, having gone to bed at 9pm, bored. I am nervous. What if they find something?

I have booked the "Executive Full Mega Super-intrusive Check-up for Women of a Certain Age" package (about HK$4,000), or something like that, so I am prepared to be inside the thick walls, and no doubt barred windows, of Bumrungrad all day.

My thoughts revolve around needles and stool samples. Will there be an anal probe? If there is, I hope it will mean eating a small camera and letting it rummage around in there by itself, not doing the tube thing with the menacing putting on of plastic gloves on an enormous hairy arm, like in those films about American prisons.

And the sample! Who can provide such a thing on demand? It's bad enough with the other one.

Ruth and I, although dithering, make it to the hospital for the 8am registration and, before I know it, I am in a room with my sleeve rolled up. Blood test! I have been fearing that, too. How pathetic am I? But before I have finished saying "hello doctor" to the nurse (I always find it useful to address people in uniform above their rank), she has put a needle in my arm painlessly and filled three vials with what seems like most of my blood. But is it blood? It is so dark, almost like old red wine. What if I have blood cancer, brought on by wrong colouring? I stagger on down the Bumrungrad conveyor belt.

When I say conveyor belt, I mean pleasant, non-hospital like corridors and waiting rooms, all carpeted and not freezing. And although there must be more than 100 patients, women and men, in various stages of examination, I move quickly from one smiling, exquisitely well bed-mannered female doctor to the next. Whisk, whisk, pap smear, whisk whisk, eye exam, swish, swish; fast, painless, unembarrassing.

When I am told to go and change into spectacularly unflattering pyjamas in the colour of "haven't eaten in two days" puke, I should feel like a chicken in a factory, plucked and vulnerable. I haven't even put on make-up, because I wanted the full institutionalised experience, and I am wearing glasses. But I feel fine! Unusually upbeat, in fact. Everything is so geared towards making patients feel like they aren't patients, I find that I am enjoying myself. Now if I could only …

Outside the changing room is a hatch bearing the sign, "Drop specimen here". Inside the toilet cubicles are reassuring cartoon posters: one depicts a very large bird visiting the doctor - female, of course - inquiring as to how it could leave a stool sample in such a tiny spoon. When we are down to the word "specimen" and no one has had to handle my inner secrets, I am convinced I can do it.

I can do it the next morning, in fact, the nurse informs me, in a soothing murmur, so only I can hear it, adding that the specimen mustn't be more than "four hours old".

Well, that is no problem, as we had the sense to book a hotel right across the treacherous road from the hospital.

Whisk, whisk I go, sashaying through the doctors. The only waiting comes between the mammogram and the ultrasound. Having not been allowed to drink since I came in, I am now told to gulp down water - and lots of it. And, wearing only pyjamas, I am suddenly a lot colder than when I came in. I begin to long for the toilet more intensely than I have since a seven-hour bus trip in Xinjiang without stops.

Advice: when they tell you to start drinking water, don't gulp it down at once but give it a good 20 minutes before you begin necking those bottles; with up to an hour of waiting before the ultrasound, you want a nicely full bladder, not a bursting one.

When I finally get to lie down and have some kind of cooling gel (I hope that's what it is) smeared all over me, the technician remarks, "Wow, your bladder is really full!" You don't say? Get on with it then, if you don't want a really nasty surprise!

I hold on for dear life, though, for only minutes earlier I smugly witnessed a mainlander in the waiting room who had been unable to wait any longer and had to start all over again with the bottles of water and the waiting.

I am surprised to see so few mainlanders on the conveyor belt. A quick glance at the computer screen the technician carelessly leaves in full view after she has wiped the gel off me shows that only three of the 12 patients who laid down in this darkened room immediately before me have Chinese names. You don't have to look at a computer screen to see who is the best-represented group at Bumrungrad, though. With the many niqabs on show, some of the waiting rooms look more like an airport lounge in Riyadh than part of a hospital in Thailand, a largely Buddhist country.

the end of my conveyor belt. The whole thing has taken about four hours, including the bladder-filling/waiting, and when I bounce out of doctor Kraphut-something-porn's office with a clean bill of health, except the mild anaemia I have always had, I feel as though I have been born again.

There is really only one negative thing I can find to say about Bumrungrad, and that's not for lack of trying! (I'm a very good negative-thing-finder.) All around the building are potholes; random, seemingly unnecessary steps and sudden depressions invisible to the naked eye. Lumps of tarmac where a staircase would have been more appropriate proliferate. Add to those hazards motorbikes and ambulances, weaving in and out of rows of wheelchairs, and even the most nimble is liable to stumble.

It's almost as if the hospital is trying to drum up its own business.

Oh yes, and the coffee is truly awful.

But what a relief it is to be told I'm not at death's door! How silly I have been, not realising I had nothing to fear but fear itself! And so, with newly liberated livers, Ruth and I set to work pummelling them into submission with excellent Singha beer.

Places to stay near Bumrungrad hospital

If you, like us, arrange for your medical blowout to start at 8am, the last thing you'll want to do is battle Bangkok's notorious traffic before you're even fully awake.

The street right outside Bumrungrad International Hospital, for example, Soi 1, in Sukhumvit, sports at least five hotels. We stayed at the FuramaXclusive, whose connection to the Furama chain of hotels is in name only. But, for about HK$300 a night, it is reasonable - and even has a pool. Its breakfast of dried fruit and yogurt was the perfect start to a day devoid of activity.

A few steps further down the street is the Best Western, which is a generic hotel except for a squashed little outside dining area with a panorama view (if you can see through bamboo) of one of the Bumrungrad exits. Its Thai food isn't very Thai - more like tentative fusion gone wrong - and the accommodation costs HK$1,355 a night upwards.

If you're going to spend that kind of money on a hotel, though, I would recommend the absolutely charming and splendid Ariyasom Villa, another 10 paces or so down Soi 1.

Set inside a garden in which the only noise comes from the occasional water taxi powering past on the canal just over the wall, the house was built by the owner's grandfather in the 1940s. Beautifully appointed with soaring ceilings, slowly rotating overhead fans, Thai-silk trimmings and luxurious rooms with French windows overlooking the pool and outside restaurant, it's a steal at HK$1,400 a night.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR: The watchtowers of Kaiping