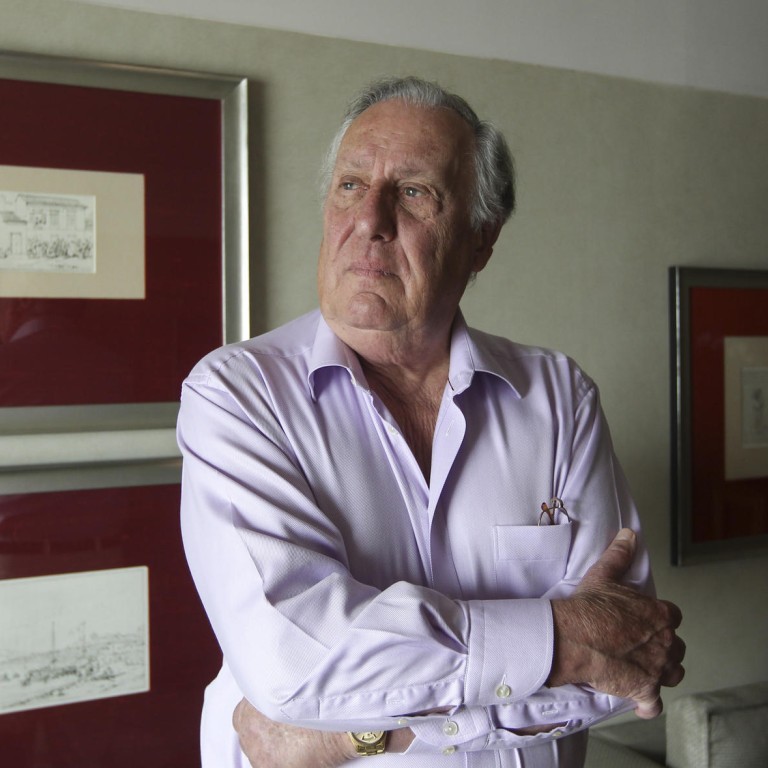

Thrills & kills: Frederick Forsyth turns to modern-day terrorism

With his latest book, master storyteller Frederick Forsyth is back doing what he does best, writes Jo Baker

Aged 75, Frederick Forsyth allowed himself a small concession in researching his latest book. In Somalia, he hired a bodyguard.

"I've only done it once before," says the veteran novelist, reclining at a desk in his Hong Kong hotel suite. "We didn't stay inside what's called The Camp - a kind of sandglass-walled and barbed-wire enclave used by most foreigners - but in a hotel in the city. Which was … interesting. My wife said I was a stupid old fool, but I felt like if I was going to describe it, I had to see it."

Fans might have forgiven Forsyth for researching Mogadishu, one of the world's more dangerous cities, from a distance. But the British thrill master felt his latest look into the world of modern-day terrorism, , should be held to the standards that helped take his 12 other novels to the top of the bestseller lists.

Having debuted as a novelist in 1971 with , Forsyth has become known for his melding of fictional characters and plot lines with real political machinations, using research techniques from his days as a journalist.

"I've always been intrigued in the things the establishment don't tell us, rather than those they do," he says, with a smile. "Nowadays we think we know it all, and Mr [Edward] Snowden tells us, 'Oh no, you don't know the half of it - what they're listening to, eavesdropping on.'"

A journalist in the 1960s and 70s, Forsyth has developed a sense for the world's lurking dangers and blind spots. Growing up in a small, "one horse" town in the southern English county of Kent, with little money, he failed to secure the career he wanted with the Royal Air Force but dreamed of travel. The idea of diplomatic corp cocktail parties, however, was less than thrilling.

Forsyth progressed from the offices of a daily provincial paper to London's Fleet Street and then to the Reuters news agency, and by the age of 23, he was reporting from Paris, France, covering the almost constant likelihood of an assassination attempt on President Charles de Gaulle by French extremists. It was a "baptism by fire", he says. This fire raged on into the mid-60s, with two years in the thick of Nigeria's civil war, first for the BBC and later - since he was unwilling to toe the broadcaster's editorial line and return to London - as a freelance reporter.

At that time, few writers had attempted to blend contemporary politics with fiction, and the decision to use his experiences in France and skills as a reporter to write a political thriller produced , his sleeper hit. Surprised but gratified, Forsyth continued to write his novels to a similar template, tackling subjects that ranged from the underground Nazi movement in Europe (1972's ) to international drug cartels (2010's ). In researching his books he has been able to pursue the thrills he spent his Kent boyhood imagining, with hairy moments, as he calls them, galore. In Afghanistan and Pakistan; Equatorial Guinea, where he blithely recalls almost losing a leg to septicaemia; and Guinea-Bissau - "a horrible place" - where he came close to being caught up in a gruesome coup.

Each adventure produced material for adrenalin-fuelled accounts of dark places and dastardly deeds, all sewn together with a reporter's eye for detail.

"Travel was the main impulse for 50 years of my life," he says. "And as an investigative journalist one learns where the knowledge reposes, and how to get at it. So that is how I approached fiction."

, which hit shelves in September, fits squarely into this oeuvre. Cold-war intrigue updated for the age of al-Qaeda, it follows a United States government-sanctioned assassin on the trail of a charismatic jihadist, and takes readers into the administrative bowels of an American organisation tasked with tracking and killing "enemies of the West". It then leads them across the gullies and firewalls of cyberspace to various havens of Islamic extremism, from London to Kismayo, Somalia. Deftly paced, the thriller has been described in reviews as being the usual meticulous yet macho Forsyth romp: heavy on action and intrigue; light on moral complexity and character development.

on drone attacks that inspired Forsyth to pick up his pen again. Not long after the extrajudicial killing of Osama bin Laden by US Navy Seals, the author became curious about how modern-day manhunts take place. Originally called , the new novel's name was changed when his American publishers called - in high excitement, he says - to inquire whether a "kill list" actually exists in the White House. Forsyth was able to tell them, rather smugly, that it does. Last year, the US government admitted publicly that it authorises "signature strikes" on certain targets, with responsibility centred on the counterterrorism chief in the White House.

Yet this batch of research posed a new kind of challenge. The author had covered the technicalities of espionage and warfare with the Arab world before, in (1994) and (2006). But to a 75-year-old who until last year had refused to own a mobile phone and continues to churn out his 10 pages per day on a steel-cased portable typewriter, cyberspace was an alien landscape.

"I had to go to people who are real cyber experts and ask them to explain as if to an idiot what they were doing and why," he says. "There was obviously a huge generation gap. A lot of the real, talented geeks are younger than my grandson." Accordingly, the novel gives out a sense of both wonder and foreboding as regards technology. "The ones who are deeply into this cyber stuff I do find very strange," he admits. "But also tremendously talented. These hackers can carve their way through firewalls in the databases of the Pentagon with something they bought at Computer World."

With weapons technology and warfare, Forsyth is on more familiar ground. His grasp of the subject has grown with each novel, along with his little black book of experts to consult. And also with each novel, doors have opened for the author at ever-higher levels, aided perhaps by a CBE (Commander of the British Empire) he was awarded in the late 90s.

"When I was much younger, particularly for the first three books, the big bosses in the forces of law and order wouldn't give me house room," he says with a laugh. "I would have to go instead to the underworld. Now, if I say to someone fairly high up in, say, [London police headquarters] Scotland Yard, that I'm writing a book on the cocaine trade, he'll put me in touch with his head of narcotics."

Forsyth tells an anecdote from when he was researching his third novel, in the 70s. He had needed to find out where and how mercenary groups in Africa bought their weapons. With the black market for arms based in Hamburg, and him being able to speak German, the author decided to masquerade as a South African on a buying expedition for a wealthy patron.

"I more or less used the plot of my book, [which was] about a mining millionaire who wanted to topple an African republic," he recalls. All went well until one of the bosses, returning home from a meeting with Forsyth and others, reportedly saw the author's photograph in the window of a bookshop. "I received a call from an insider friend in my hotel room, who said, 'Grab your passport and money and run like hell!' Fortunately I was in the train station hotel, so I ran across the square to the station, vaulted the ticket barrier and dived straight into the window of a departing train - into the lap of a German businessman who had a sense of humour failure."

He didn't go back to Hamburg for years.

"The book came out in German with [the men] very thinly disguised, and I hear they didn't like it at all," he says.

Compared to that, he admits, his recent "reccie" in Mogadishu was leisurely.

As a search-engine sceptic, Forsyth makes heavy use of industry publications, such as those from Jane's Information Group. His books are populated with the likes of Ukrainian freedom fighters, French paramilitaries, Gulf war soldiers, Somali pirates and al-Qaeda members - along with American and British special forces and spies. All are often locked in combat and armed to the teeth. Keeping up with the fast-moving world of weaponry is no small feat, particularly so with his weapon of choice in drones.

"These drones are being modernised and improved all the time, so the stuff from just 10 years ago is outmoded," he explains. "But the information is mostly in the public domain. If you know where to go, there's probably a technical publication that tells you exactly what it does." At times his digs into the field have been met with warnings, he says, about breaking Britain's Official Secrets Act. "I tell them, 'Don't worry - you can read all that in !'" he says with a chuckle.

"I think there's a lot of nonsense talked about the immorality of drones," he says. Those who challenge their use tend to question how any country can strategically use lethal force against individuals without a trial, and outside of a "symmetrical" war. "If it's a legitimate target, what's the immorality in destroying it? We are in a defence posture against these terrorists, and when we find them we have a right to defend ourselves from them killing us."

He adds: "I don't recall that we declared war on Islam. But certain elements of Islam are at war, which they call jihad, with the Christian-Jewish world."

Forsyth will acknowledge that in Britain the left has "given up" on him, but he insists his politics are "conservative with a small c". He calls the euphemism "war on terror" - coined by the administration of former US president George W. Bush - "manure" and claims no interest in British party politics. What he stands for, he explains, is more of a "traditionalist attitude" to life.

"It seems to me our forefathers got an awful lot right," he says. "And I've never seen why anyone should be ashamed of loving one's own country. It seems modish now not to, and I rebel against that. And for it, I'm called right wing."

He has often lamented that he was born in the wrong era. Given the choice, he would have lived through the second world war and what he considers his nation's finest hour: the Battle of Britain.

This sentiment runs thick through his books. They vibrate with faith in the hard-boiled integrity of his mostly white, male government operatives; with reverence for men in combat and for action over ambiguity; and with the cut-and-dried morality of good guys vs bad guys. Plot lines are streaked with a boy's thrill for heroism and love of aliases, acronyms and techno-speak - at the expense of inner dialogue or political nuance. He rarely uses anti-heroes, he says, which tend to be less popular with his readership.

However, "I've never hidden the fact that if it didn't pay, I wouldn't do it," he says of writing fiction. "It's more about the bank than the message for me."

For Forsyth, the public's consistent fascination with spies and terrorist hunters has fitted neatly with his own interests and skill set, becoming a cash cow that, he says, he has been happy to milk.

"There's still fascination with this constant war of spies, which some - not I - thought falsely would be over when Soviet Union collapsed," he says. "In fact it's trebled. "The problem is that 99 per cent of espionage is bureaucracy, scanning communications and technical information. And there's no James Bond wandering around out there," he says, gesturing to the Hong Kong skyline. "There are probably a few spooks, but they're probably rather shabby little people. So yes, there is a false glamour."

Which his books perpetuate? "Yes," he laughs. "Or at least a bit; because most people have a banal existence, and it's what they want. That's not patronising. It's a fact of life."

Yet the size of Forsyth's "conservative c" seems to be larger - or to have been becoming larger - than he will sometimes allow on book tours. Touted as a "bestselling author and political commentator" by the British newspaper , for whom he writes a column, his claim to not be sending messages through his work seems disingenuous.

In his column, Forsyth has written passionately and divisively about those who hate the West, and the heroism of those who protect it. A few weeks ago, writing in support of the "spooks" and special forces he has interviewed throughout his career, the author consigned whistle-blowers to the seventh circle of hell. "Revealing secrets that enable jihadists to penetrate our defences, all the better to place bombs where you and I go shopping, that is traitorous," he wrote of a "whingeing and whining" Snowden, whose whistle-blowing on the extent of the US National Security Agency's surveillance activities brought him to seek refuge in Hong Kong earlier this year. "Dante reserved the seventh and innermost circle of Hell for the betrayers and he was right," the piece went on.

Forsyth says he spent substantial time researching the forms of Islam that feature in , and he was keen to present the disdain of moderate Muslims towards fundamentalism. He describes long doctrinal discussions with a British imam who became a Muslim voice of reason in the plot as a professor based in Cairo's revered centre for Islamic learning, Al-Azhar University. In researching the motives of young jihadists, Forsyth consulted the co-founder and chairman of London-based counter-extremism think tank Quilliam, who had once led an extremist movement and later repented. "He could explain to me why the jihadists think the way they do," says the author. "I was trying to hear both viewpoints."

Yet his grasp and representation of the religion and its politics have still left many cold. One Asian fan on a review site suggested the religious aspect was unconvincing, and that the book would have worked better without trying to tackle it. "The author raises the question 'Why do they hate Americans?' and answers this complex issue very superficially, almost offhandedly," she or he comments. "The book is good [but] it's not about Islamic fundamentalism. The flaws are perhaps more visible to Asian minds than to Western ones."

Indeed, there is a sense that , with its parallel, polarised universe, fails to address the reality of terrorism, and rather reduces it, as one reviewer noted in , to the simplicity of movies and video games. For all its up-to-date technical wizardry, it still feels, to this journalist at least, rather wistfully behind the times.

Yet a cash cow the formula remains, and Forsyth's success and reputation as thrill master seems secure. Last year, the Crime Writers Association awarded him its Cartier Diamond Dagger for his body of work; and has perhaps not surprisingly been embraced by Hollywood: it is due to be made into a film directed by Rupert Sanders.

But could this be an end to adventures in Mogadishu? Sitting in his hotel suite and preparing for lengthy anniversary celebrations in honour of his host, the Mandarin Oriental, the septuagenarian is tired. He has threatened to retire numerous times. Now, with 70 countries visited and 20 books, fiction and non-fiction, under his belt, he feels this could really be it.

"There are people who are compulsives, who are not fulfilled unless they're writing. But I am not one," he says. "I have to be dragged to my typewriter now. There are so many other things for me to do. And really - I don't have a message for the human race."

This remains under debate, but any decision to end his writing career will leave legions of disappointed thrill-seekers in its wake.