The ethical travel group teaching tourists to respect, support and learn about places they visit

- Hong Kong-based Civil Wayfarers hopes to change not just how tourists see other countries, but more importantly, how they see themselves

- Co-founder Wong Kim-fan says the biggest problem with travelling now is that people are not aware of the impact they are having

Wong Kim-fan, a part-time lecturer in the philosophy of travel at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), first learned about the Silk Road as a 14-year-old high-school pupil when a substitute teacher played a documentary exploring long-lost civilisations along the ancient trade route.

Mesmerised, he immediately planned a trip to northern China. It was the first time Wong, who was raised in a working-class family, had ventured outside his hometown of Hong Kong.

“Learning history is just not the same once you’ve personally been to the places in the textbooks,” says Wong, whose adventure inspired a lifelong passion for travelling.

Nearly two decades and countless trips later, Wong combined his own experiences under a theoretical framework to study why people travel today. He arrived at some disturbing findings.

There has been a huge transformation in how and why people travel, he observes.

With the rise of the middle class in emerging economies such as China, India and Brazil, millions more people have the luxury of taking a holiday abroad. Budget airlines, which have undergone rapid expansion in the past decade, enable frequent flying, justifying even weekend international getaways.

Then there is social media, where influencers flaunt their globetrotting careers as glamorous, desirable lifestyles and encourage others to try it. Instagram has become not just a platform to document your travel, but the reason why people do it in the first place.

All these trends have contributed to what Wong foresaw as an alarming phenomenon – a massive surge in global travel. This is backed up by data from the United Nations’ World Tourism Organisation, which predicted in 2010 that international tourist arrivals would reach 1.4 billion in 2020 – but that figure was reached last year, two years early.

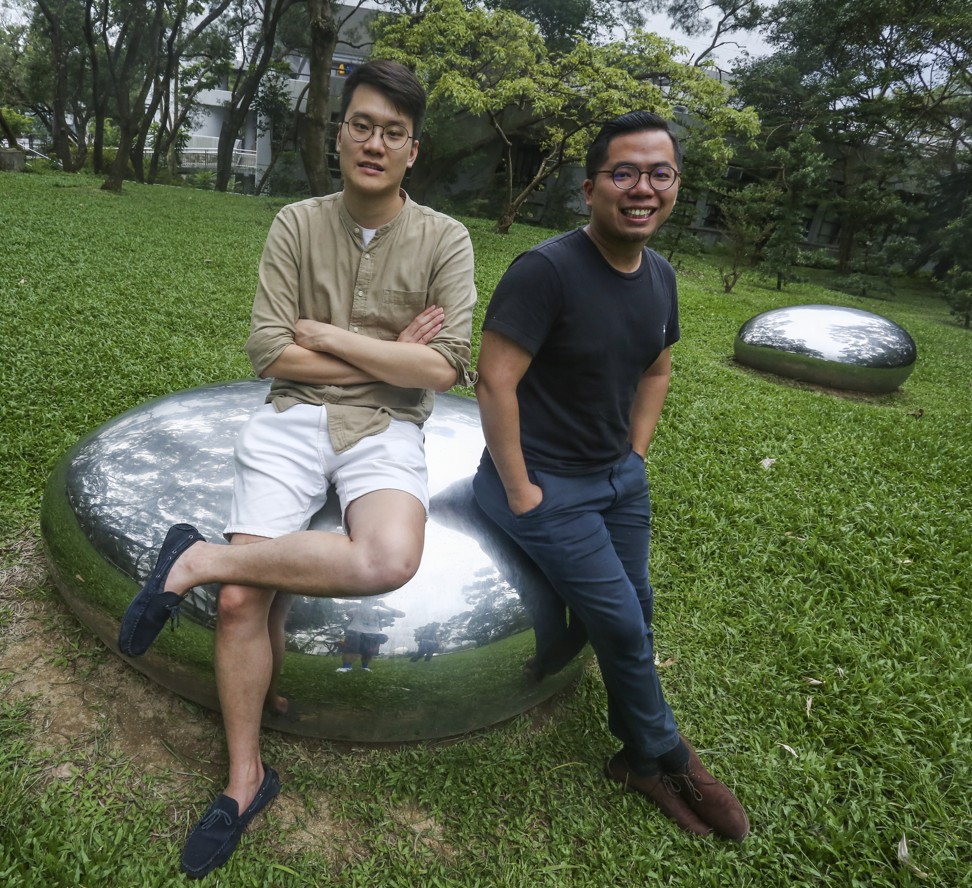

Wong has co-founded an initiative called Civil Wayfarers to promote ethical travel through education. His partners, Rubio Chan Shing-kwan and Jamie Cheung Chun-wa, run GLO Travel – a company that organises tours to unusual destinations such as North Korea, Kazakhstan and Iran – while media veteran Allan Au Ka-lun is their consultant.

In the pipeline are detailed guidelines on best practices when visiting certain countries, with Wong and others writing from their own experience based on careful research.

“Many [suggestions from others] encourage people to support local businesses, but tourists can easily go to what look like local restaurants and stores only to realise they are part of a global chain,” Wong says. “We identify actual local markets and businesses for you, where your consumption actually goes into the pockets of residents.”

Another guideline: “Don’t haggle if you are in a poverty-stricken country.”

Some of the funds raised by Civil Wayfarers from its talks are donated to local NGOs. The remainder goes toward sponsoring disadvantaged Hong Kong children to travel abroad. This is to change what Wong calls the “exposure gap”, where students from privileged backgrounds get to travel far and wide while “some raised in [Hong Kong’s northern] Tin Shui Wai [district] have never even been to Hong Kong Island”.

“Being able to travel is actually a huge blessing,” Wong says. “So if we can gather the power of those who can afford to do so, we can make an impact.”

Civil Wayfarers hopes to change not just how tourists see other countries, but more importantly, how they see themselves. Tourists, Wong says, are increasingly seeing themselves not as visitors in other people’s territories, but as customers who expect to be served and entertained.

“The biggest problem with travelling now is that people are not aware of the impact they are having,” Wong says. “They think of it only in positive terms – that their consumption is contributing to the local economy – without realising how insignificant that actually is, or the negative effect their presence and behaviour can bring.”

To get his point across, we meet at CUHK’s Pavilion of Harmony, a scenic spot on campus that offers an unobstructed view over the Tolo Harbour in Hong Kong’s rural New Territories. These days, however, harmony is rarely experienced here. Instead, enthusiastic photo-takers and tourists constantly stream by, leading to complaints from students living nearby. The situation was made worse when the pavilion began to feature on lists of Hong Kong’s top Instagram spots.

This is but a small example of what is happening on a much larger scale around the world, Wong points out.

“It’s a matter of proportion. Think of your home. You probably wouldn’t mind hosting a few visitors once in a while. But what if dozens cram themselves in every day, jump on the sofa and wreck your place?”

What we can do is very limited. But we hope that, little by little, we can minimise and compensate for the impact we, as tourists, have on other places

He points to other detrimental and more sinister ramifications of overtourism, citing Cambodia as an example. Travellers feed a thriving human-trafficking industry in the Southeast Asian nation which, according to anti-child-abuse network ECPAT International, “is a key destination for the sexual exploitation of children in travel and tourism”.

Also emerging in Cambodia are bogus orphanages, he says. Critics describe them as a form of modern-day slavery, where organisers recruits children to pose as orphans and attract paying foreign volunteers. Meanwhile, tourism gentrification regularly occurs as large visitor numbers drive up property prices and the cost of living, forcing less-affluent local residents out of core areas of the cities.

Like Wong, Chan and Cheung believe the solution to overtourism is not necessarily to discourage travelling. They think that besides tourists being more mindful of the impact they have, greater immersion into destinations could be the way forward.

Chan and Cheung were so bored with their office jobs they decided to turn their enthusiasm for travelling into a business.

To test the water, they organised a day trip for a group of university students to Macau, an hour away by ferry from Hong Kong. By watching a drama performed in the disappearing language of Patua – a blend of Portuguese and Cantonese spoken by the indigenous people of Macau – the students learned about Macanese culture and saw another side to the Asian casino capital.

The trip’s success encouraged the duo to launch GLO Travel.

“We try to add intellectual and cultural elements to each trip, so participants really feel they have gained knowledge and a deeper understanding of the places they’ve visited,” Chan says.

Most of the company’s trips are led by unlikely tour guides and follow unconventional itineraries off the beaten track.

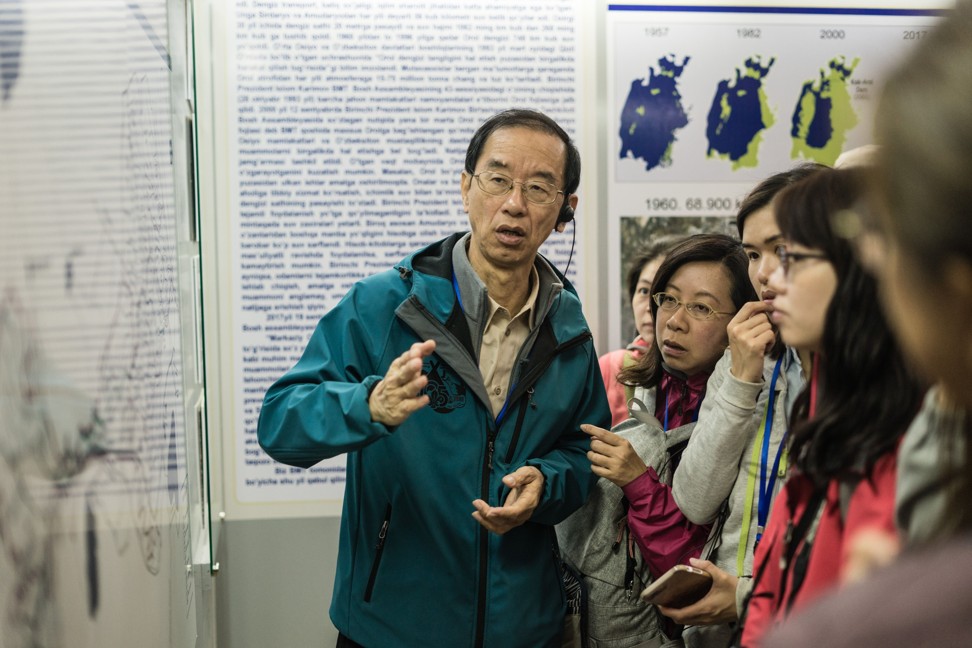

For example, one group was shown around Uzbekistan in Central Asia by Lam Chiu-ying, former director of the Hong Kong Observatory and an environmental activist. One site they visited was on the banks of the shrinking Aral Sea, where they witnessed first-hand the devastating impact of climate change.

Another group explored Ukraine with veteran war correspondent Susanna Cheung Chui-yung. They visited Chernobyl to witness the aftermath of the tragic 1986 nuclear accident and meet an activist who took part in Ukraine’s 2014 Euromaidan revolution.

On a tour to Russia led by Wong, the group read from the George Orwell classic Animal Farm at the Palace Square in St Petersburg, and walked through “micro districts” planned by the former Soviet Union, to understand how life has changed for residents since the fall of communism there.

Through understanding the social problems local residents face, tourists learn about their own responsibility as global citizens. They can also find out how to be of help thanks to information on local societies included in the tour company’s itineraries.

On a tour to Bhutan, for example, a group visited an NGO that seeks to improve hygiene conditions and build public toilets in rural areas. In North Korea, travellers shared hygiene skills with deaf-mute children at an NGO run by a German.

“What we can do is very limited,” Chan says. “But we hope that, little by little, we can minimise and compensate for the impact we, as tourists, have on other places.”