Zhoushan, the Chinese island that was very nearly Hong Kong, hasn’t forgotten the opium war

Six months before the British flag was planted in Hong Kong during the first opium war, British forces took Zhoushan. While few in the West remember the details of that conflict in eastern China, Zhoushan hasn’t forgotten

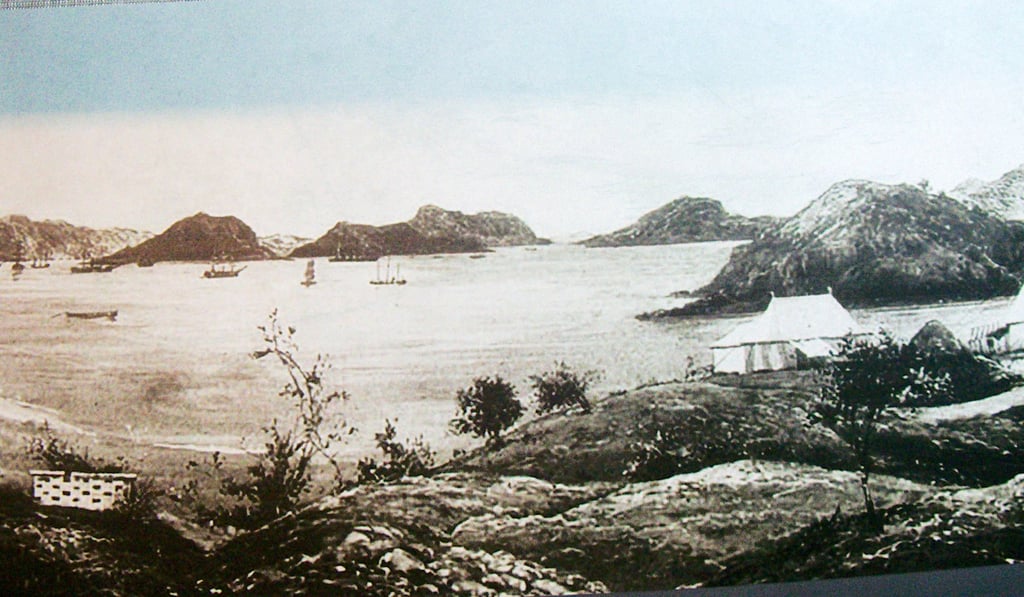

When British diplomat Sir George Staunton arrived in Zhoushan (or Chusan as it was known in the West) aboard warship HMS Lion in 1793, he warmly described the island’s main harbour town of Dinghai as comparable to Venice.

He was not alone in his admiration. The East India Company had first tried to establish a British trading base in Zhoushan in 1700, and for the next 150 years, the British eagerly continued the effort, long before anyone considered the merits of Hong Kong.

Who caused the opium war? British merchants of Canton, argues new book by Singapore academic

Today, as my bus speeds past the smog-shrouded forest of chimneys and cooling towers that make up Ningbo’s industrialised eastern suburbs, en route to modern-day Zhoushan, it is difficult to share their enthusiasm.

“Dinghai nowadays is becoming more a city of shopping malls and skyscrapers – no Hong Kong, certainly, but no boondocks either,” says Liam D’Arcy-Brown, author of Chusan, a detailed history of European interest in the island published in 2012. Brown has kindly offered some guidance for the trip.

As the smog clears and the city of Dinghai comes into view in weak sunshine, it is easier to understand the attraction. The town’s picturesque harbour offered British ships a well-protected deep-water anchorage, and an easily defended settlement in proximity to key trading centres in the Yangtze valley for much-coveted tea, porcelain and silk.

Today, the harbour is studded with dozens of modern merchant ships and narrow river boats, which cluster around the sleepy civil passenger terminal. It is hard to imagine that during the 1840s there were some 5,000 Europeans living in this area.