Why China will be next Silicon Valley, says LVMH digital head, and how French start-up culture is catching up

Ian Rogers, LVMH chief digital officer and a former Apple and Beats executive, talks luxury online retail, start-up ‘scaffolding’ in France, and why the next Google or Facebook is likely to be from China

Furnished with music memorabilia, black and white photos of skaters and an Apple TV, the office of Ian Rogers, at the LVMH headquarters on Avenue Montaigne in Paris, is not what you would expect from a top LVMH executive. But then again Rogers, a skateboard-obsessed former roadie for the Beastie Boys turned music-industry mogul, is not your average luxury honcho.

Often clad in his signature uniform of T-shirt, jeans and beat-up Vans, Rogers was born in the US state of Indiana and was at Apple Music when LVMH hired him as chief digital officer in 2015. He was previously at Beats Music and moved to Apple when the Cupertino-based technology giant took over Beats in 2014.

Why LVMH scion won’t be wearing Virgil Abloh’s Louis Vuitton

While his background might seem an unusual match with LVMH – “I’d never done physical stores or China before this job” – his hiring was a clear sign that the company was getting serious about all things digital.

Rogers’ arrival at LVMH coincided with the launch of 24 Sevres, the company’s multi-label e-commerce site which competes with websites such as Net-a-Porter and matchesfashion.com. His remit, however, extends beyond online retail to encompass LVMH’s entire brand portfolio and how the company uses technology to build awareness, gather data, interact with its customers and create a seamless omnichannel shopping experience.

The way Rogers sees it, “digital” is an obsolete word for any company trying to be relevant in the 21st century.

“If you tell me you’re behind in digital, then you’re behind in every part of your business,” says Rogers when we meet him in Paris during the couture shows in July. “Which part of your business hasn’t been transformed by internet-connected consumers? From materials to supply chain to building awareness and sales – when companies say they’re investing in digital, they mean that they’re catching up to consumers who have evolved because of the internet and mobile phones.”

Rogers admits that LVMH was late in its digital transformation, but says this was not necessarily all bad. “The biggest thing the luxury industry had a misconception on is that they felt that they had to be early adopters. But if you think of the adoption curve, you don’t want to be too early or too late, but rather in the middle or just before mainstream,” he explains. “In the ’90s LVMH was an early adopter when it was investing in companies, but recently they were late adopters and had to catch up in order to be in the right place.”

When you sell Eminem, the rapper, you’re not selling a music file but rebellion, culture. It’s the same when you sell a handbag; you’re also selling the brand

Rogers believes the luxury industry was hesitant to join the digital revolution because companies worried their products would become too commoditised online. He says, though, that “online doesn’t change accessibility”.

“Anybody can walk into a Louis Vuitton store; it’s not like a club. The products are exclusive for other reasons – maybe because they’re genuinely scarce or very pricey. What you really want to get right online is your experience; it’s not about online versus offline. Let’s face it – our customers use Uber and Amazon and have been to the Apple Store so they know what a great customer experience feels like. Look at 24 Sevres. It’s not like Amazon, not just a transaction.”

In that respect there are clear links to his old jobs. “There are similarities between music and fashion. They’re both culture businesses,” Rogers says. “When you sell Eminem, the rapper, you’re not selling a music file but rebellion, culture. It’s the same when you sell a handbag; you’re also selling the brand. That’s part of the value of the price.”

He believes that online and offline can complement each other as long as physical stores provide unparalleled customer experience. He mentions Le Bon Marche, an LVMH-owned department store in Paris, as an example of bricks-and-mortar retail done right. “You can go there and buy groceries, eat oysters, buy vinyl or get a cup of coffee, but you can also buy a €3,000 [US$3,400] dress,” he says. “It still does what a store does, but you go there because it’s a great place to go, not just to buy a dress.”

Rogers is adamant that the luxury industry has benefited from the way the internet has created so many niches in the global market and has moved it away from mass consumerism, despite some luxury CEOs thinking otherwise.

“Fundamentally, the internet is changing humans to a market of tribes, where marketing is not hyper efficient but quality is,” he says. “Take Netflix: their shows are popular not because they’re good at investing in marketing but because the shows are actually good. Now look at LVMH: a mass of niches where you have an obsession with quality, creativity and craftsmanship. That just works. Luxury has a business model that’s perfectly suited for digital but you need to add a little bit of structure because LVMH exists to add operational efficiency to creative people.”

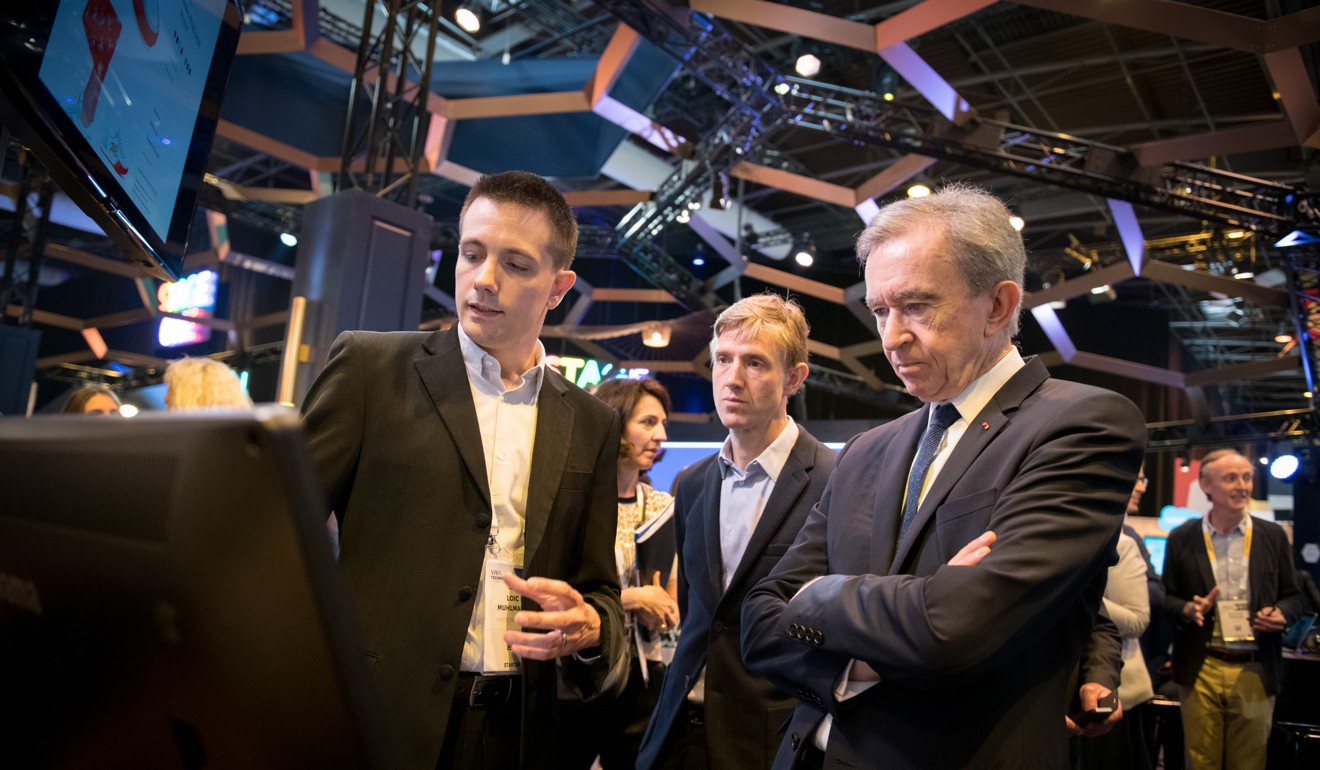

While “creative people” at LVMH used to mean designers and luxury experts, things have been changing. This year at VivaTech, an annual tech convention in Paris, LVMH had a large presence at the stand of Station F, a French business incubator that funds and develops start-ups. During the event the company also gave out its LVMH Innovation Award, which this year went to Oyst, an online payment system similar to Apple Pay and Alipay.

“I saw the music industry trying to kill all the music start-ups,” Rogers says. “But we want to support the start-up ecosystem because a rising tide lifts all boats. If the industry is healthy we all benefit from that growth, so we’ve built a pipeline.”

But old Europe is still a long way from being anything like Silicon Valley. “France has great schools and great engineering talent but that talent was leaving the country to go to other places like the US or Asia,” he says. “We’re experiencing a bit of a bubble at the moment with Brexit [because people are thinking twice about London], but it will subside. But what things like Station F bring to Paris is scaffolding. We’re trying to build something real so that even when the city is not the shining item of the moment, there’s still something.”

Artificial intelligence [in China] is like electricity in France and they have scale of people and scale of data

Rogers is effusive in his praise of French President Emmanuel Macron, who he admires for instituting a start-up visa for foreign workers, but he still believes that Europe has a long way to go in developing a start-up culture to rival the world’s best.

“There’s just nowhere in the world like Silicon Valley – not even in the US. When people talk about start-ups in the US, they actually mean Northern California,” he says. “But China is obviously the other place because there you have capital, education, a six-day, 12-hour work week. Artificial intelligence there is like electricity here and they have scale of people and scale of data. I don’t know if the next Google or Facebook will come from Shanghai, Beijing or Hangzhou but it’s unlikely it will come from somewhere other than Silicon Valley or China. Europe is a much better environment than it was five years ago but … it’s something that France can’t fix. It’s Europe that has to fix it, not France or any other one country.”

Rogers recognises that he was not an “obvious choice” for LVMH and is part of broader change among the top ranks of LVMH. Another US Midwesterner, Virgil Abloh, recently joined LVMH’s flagship brand Louis Vuitton as its men’s creative director, the first black man to be appointed by the group to such a role.

“He grew up four hours from where I did,” Rogers says. “What did we grow up loving? Music and skateboarding. I don’t think that there’s a direct relationship with that but I always joke that anyone who made a fanzine with a magic marker understood the internet from day one. I think that there’s something to what we’re feeling culturally that really fits.

The fashion influencers helping Chinese choose style for self-expression

“Did I know these luxury brands inside and out? Not really. But it made sense for me because I came from skateboarding, a tribal culture that’s not about mass market but about loyalty. I have a skateboard in that box,” he says, pointing to a Louis Vuitton trunk made in collaboration with streetwear label Supreme – an apt symbol of the sweeping changes happening at LVMH and elsewhere in the industry.