Chinese girls return to orphanage 14 years after adoption by US families to highlight plight of ‘left-behinds’

Abigail Anderson and Bingjie Turner lived in an orphanage in Qinghai before being adopted by American families. They returned to bring attention to those who aren’t adopted, and who struggle to survive when they leave the home

When Abigail Anderson and Bingjie Turner returned to China’s Qinghai province, and the children’s home where they lived before being adopted and taken to the United States 14 years ago, the most poignant moment was a reunion with friends they had left behind.

“There were a lot of tears,” says Anderson, now 28. “They couldn’t believe we were really there. We had to say to them, ‘Stop crying, stop crying.’”

The main reason they wanted to go back, she says, was to meet the other orphans they’d shared the home with, and find out how they were faring as adults. “We wanted them to know that even though we are gone, we have never forgotten them,” she says.

Anderson was adopted by a family in the state of Virginia, and Turner by a family in Seattle. They are among the lucky ones. About half the 400 children who have been cared for in the Xining Children’s Home run by Hong Kong charity Christian Action have found adoptive families overseas, mostly in the US.

Reports of parents’ deaths by China’s ‘left-behind’ children prompt a closer look at the family dynamic

The others are known as the “left-behinds” – children, often with severe disabilities, who find no one to adopt or foster them, and who struggle to survive when they leave the support of the children’s home at 18. In two recent cases, former residents have been found dead alone.

Now the charity has launched a “Back to Serve” programme to encourage former residents to return and work in the home to build bridges between the home and adoptee countries, and highlight continuing issues faced by abandoned children in one of China’s poorest provinces.

Anderson and Turner were the first to return under the programme and next month they complete a six-month stay in Xining that has brought bittersweet memories flooding back – of the trauma and upheaval of their own childhoods.

There is less child abandonment. Girls are not abandoned to the extent they were in the past

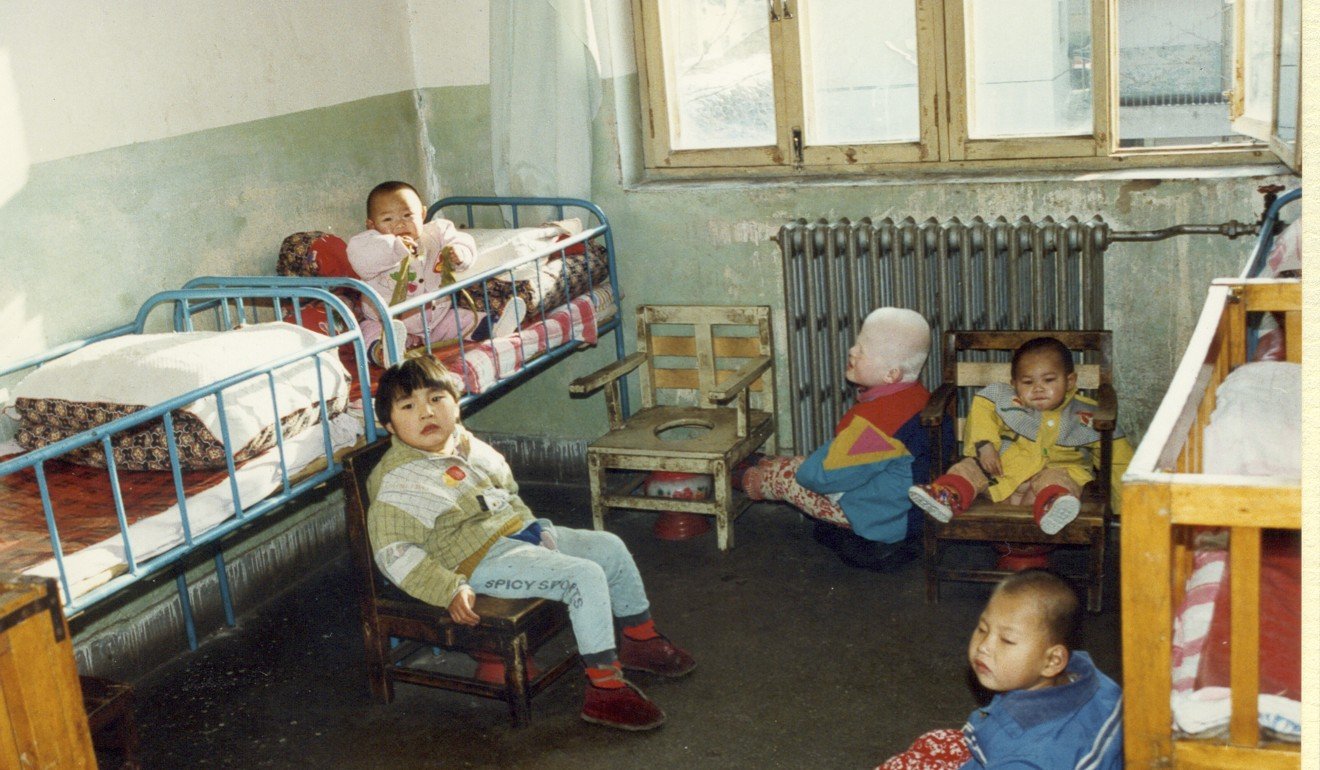

“We used to play with dirt and leaves – that was all we could find. It was a really poor place. There were no nutritious meals. The accomplishment in those days was just to keep us alive.”

Then, in 1998, Christian Action Hong Kong opened its Xining Children’s Home in partnership with the provincial government and began providing dedicated care, schooling and medical aid for the orphans.

Anderson’s childhood was transformed, and in her last years in the charity’s care she lived in a small home group of six with Turner and other youngsters and carers designed to replicate a family unit. In 2003, two weeks short of her 14th birthday, she was adopted by a family in the US.

“When I got to the US, it took me a full year at least to adjust. I didn’t speak any English and my family didn’t speak Chinese. We used to communicate by drawing pictures or we’d phone the adoption agency and ask them to translate.”

Abandoned in China and adopted to the US, an American teen’s journey in search of her roots

Everything was so different, she says, recalling her first day at school. At 2pm, the other students started packing their bags. Then her adoptive parents turned up to take her home.

“I had no idea the school day would finish so early. In those days, my parents did all they could to help. They took me to Chinese churches and restaurants just so I would have contact with other Asian people – and none of these places were close. They were at least an hour’s drive away.”

Turner, now 27, lost her mother when she was five and lived with her father until he died of liver cancer six years later. “I have a lot of good memories of my father,” she says. “He took care of me by himself and he was the best father I could have had.

Turner was adopted by a family in Seattle in 2003 and kept in touch with Anderson in Virginia, despite the 4,800 kilometres separating them. “We used to see each other – most of the time I would go to Seattle to see Bingjie,” Anderson says.

It was a really poor place. There were no nutritious meals. The accomplishment in those days was just to keep us alive

“We always had the desire to come back to Xining at some point in our lives. I told [Christian Action] I always felt it was my calling to come back to Qinghai to serve.”

When they did return in June, they found Xining a starkly different place to the relatively backward city they left as teenagers. “It was surreal,” says Anderson. “There’s so much construction going on, we didn’t recognise parts of it at all.”

Turner says that when they got to the children’s home, she noticed the walls were decorated with cartoons and beautiful artwork. “I thought, it was never like this when I was a child. It’s so much warmer and so much better.”

After their experience of caring for children at the home over the past five months, both former residents say they will return – and would like to see more done for the children destined to be tomorrow’s left-behinds.

Mother’s Choice: caring for Hong Kong’s pregnant teenagers and their babies since 1987

“It is only the more able kids who are fostered or adopted,” Anderson says. “The severely disabled ones are left behind. It is too hard for people to care for them, and they never know what it is like to have a family.”

Cheung-Ang Siew Mei, executive director of Christian Action, says the tragedy for left-behind children is that they have to leave the children’s home at 18 and often fall into depression when they find a lack of support beyond its walls. “Most of these young people are not well to begin with, and we found out recently that two of them had died,” she says.

“They didn’t die as children, they died as adults. We feel we have a responsibility to go back and look after the children who weren’t adopted.”

“A lot of them are very frail. They can’t move. They have all sorts of problems,” says Cheung-Ang. “If you don’t care for them, they die early. They are dying without dignity. We felt it wasn’t fair for them to get depressed and want to die. We want to give them a life and teach them to live independently.”

The Hong Kong charity now has five orphanages in China, including a 500-child home in the Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture.

I thought, it was never like this when I was a child. It’s so much warmer and so much better

Evolving social attitudes have also improved life for abandoned and unwanted children.

“There is less child abandonment,” Cheung-Ang says. “Girls are not abandoned to the extent they were in the past, and people are more willing to bring disabled children to our home for treatment and special-needs education.

“I suspect that has to do with being out of really dire poverty. People used to be really poor in Qinghai, and when we first went there in 1996, it was a very different place. It has almost gone from Third World to First World in that time.”

“Everyone thinks China is now a wealthy nation and they are not willing to give at all. We have tried to raise funds in the US and the UK, and it is really difficult. Hong Kong is slightly better,” she says.

“We are reaching out to people who are more enlightened about what is going on. Although China is becoming a rich nation, the wealth is not going to the poor because there are so many of them.” It’s children who miss out, she adds.

Chinese brothers, abandoned by family, forced to live in school for four years

Cheung-Ang hopes the emotional experience of Anderson and Turner with the Back to Serve programme will help build bridges that can provide not only for abandoned and orphaned children, but for the left-behind former residents.

“We have been in Qinghai for 20 years now and these girls have come back,” she says. “For me, it’s like a dream come true. I truly hope more adopted children will follow in their footsteps.”

Details of Christian Action’s Back to Serve programme are available at christian-action.org.hk/