To the Nth degree: full-colour, fully scored N++ is massive game

With more than 2,300 levels, its creators estimate that even the sharpest players will be in N++ for at least 30 hours

Just over a decade ago, Raigan Burns and Mare Sheppard released as a reaction to all that was excessive in video games.

They swapped out flashy colour for essentially various shades of grey, there was no musical score and if you were looking for a story, forget it. The main character was a tiny stick-figure ninja that could jump high and run fast as robots chased it around a minefield of explosive objects. The end.

There’s been some kind of nuclear Armageddon that obliterated one of the dimensions

Now, speaking ahead of the release of , the second proper sequel in what has proved to be a rather venerable indie franchise, Burns and Sheppard aren't quite as minimalistic in their gaming views. They have an audience, and the two wouldn't mind expanding it.

The latest edition of their game came to the PlayStation 4 as a downloadable title last month. It follows the 2008 release of , an edition that Sheppard estimates sold more than 400,000 downloads. That's been enough to allow the duo to make games full time, as well as wonder why their title hasn't reached even more players.

"It's never got the recognition that we at least feel it deserves," says Sheppard. "We thought that part of that was because it's a little unapproachable. We wanted to give it one last shot and make it a bit more friendly."

As a result, features a robust musical score (more than six hours) and no shortage of full-screen colour - blues, pinks and more in neons or pastels. Or, if the player so desires, those familiar grey tones.

even comes with a story. Well, sort of. "We'd have to look at our notes," Burns says, admitting that they don't always remember exactly what that narrative is.

"For sure, this is the future," Burns says. "It's a vaguely techno-futuristic world, and there's been some kind of nuclear Armageddon that obliterated one of the dimensions. That's how we explained that it's in 2D. Beyond that, you have a high metabolism. That's why you can only live for a minute and a half."

Despite all the upgrades, the franchise does still buck conventions, such as the long-held video game strategy to collect coins or objects to gain extra lives.

In , coins buy you only extra time, and time is always running out. If the robots don't get you, or you correctly read a jump and don't fall to your death, the clock, which starts in each section at 90 seconds, will still be ticking, and you'll still have just one life.

It gets tense quick. There are quirks that will be discovered only by failing. For example, falling from a great distance will explode our ninja, but if the ninja lands on a wall that's angled, the character will glide to safety. What's more, jumps can be controlled slightly in mid-air, which means that it's sometimes less about perfect timing and more about perfect steering. This means that there's often more than one solution to each level and that there's room for improvisation.

It also means is massive. There are more than 2,300 levels, and its creators estimate that even the sharpest players will be in for at least 30 hours. Levels can take as little as a minute or as long as 20 depending on your skill level.

The game began as a title that could be played inside internet browsers, and it owed a debt to such giants of the '80s as . It was easy to play, as it used staples of the platform genre - run, jump - and distilled them down to one screen. It was uncluttered, aside from the robots and landmines, and its corridors and caverns felt spacious and clean. Now, with the addition of a full swathe of colours, feels like the inside of a very dangerous, very deserted rave.

Still, Burns says the two struggled with the music. Too fast, and the game was too stressful. Too ambient, and the game was too relaxing. Somewhere in the middle, and the game feels like modern life.

"There were a lot of eerie parallels to how we were feeling psychologically," Sheppard says of the series. "The feeling of not having enough time, as well as how the idea that time is money in capitalism. We found it was more fun to make something and then figure out what it means. If you make it, and try to make it good, you will end up injecting a lot of stuff in there accidentally. That's more interesting than trying to construct a message."

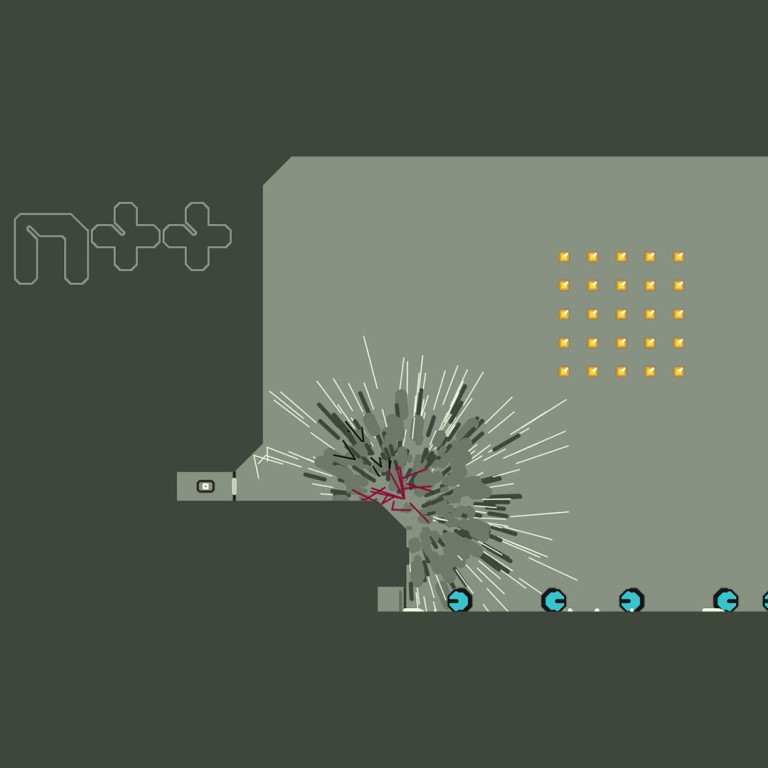

Death in is a moment of great release. At last, in peace, our ninja explodes in a grand pyrotechnic display, with each arm and leg setting off more explosions in this once-pristine world. It makes losing its own special treat, or reward.

"It's win-win," Burns says, before cautioning that one not read too deeply into it. "We think there's not enough slapstick in games."