K-pop, K-dramas, K-movies, now art: is Seoul the cultural hub of Asia? Frieze art fair’s debut there at least suggests South Korean capital can be regional centre for art trade

- Does the success of Frieze Seoul make the South Korean capital Asia’s cultural hub, as its mayor says? It certainly affirms its role in the global art market

- With 450 registered galleries, and international players favouring Seoul for its ‘feeling of stability’, the capital’s art scene looks set to continue growing

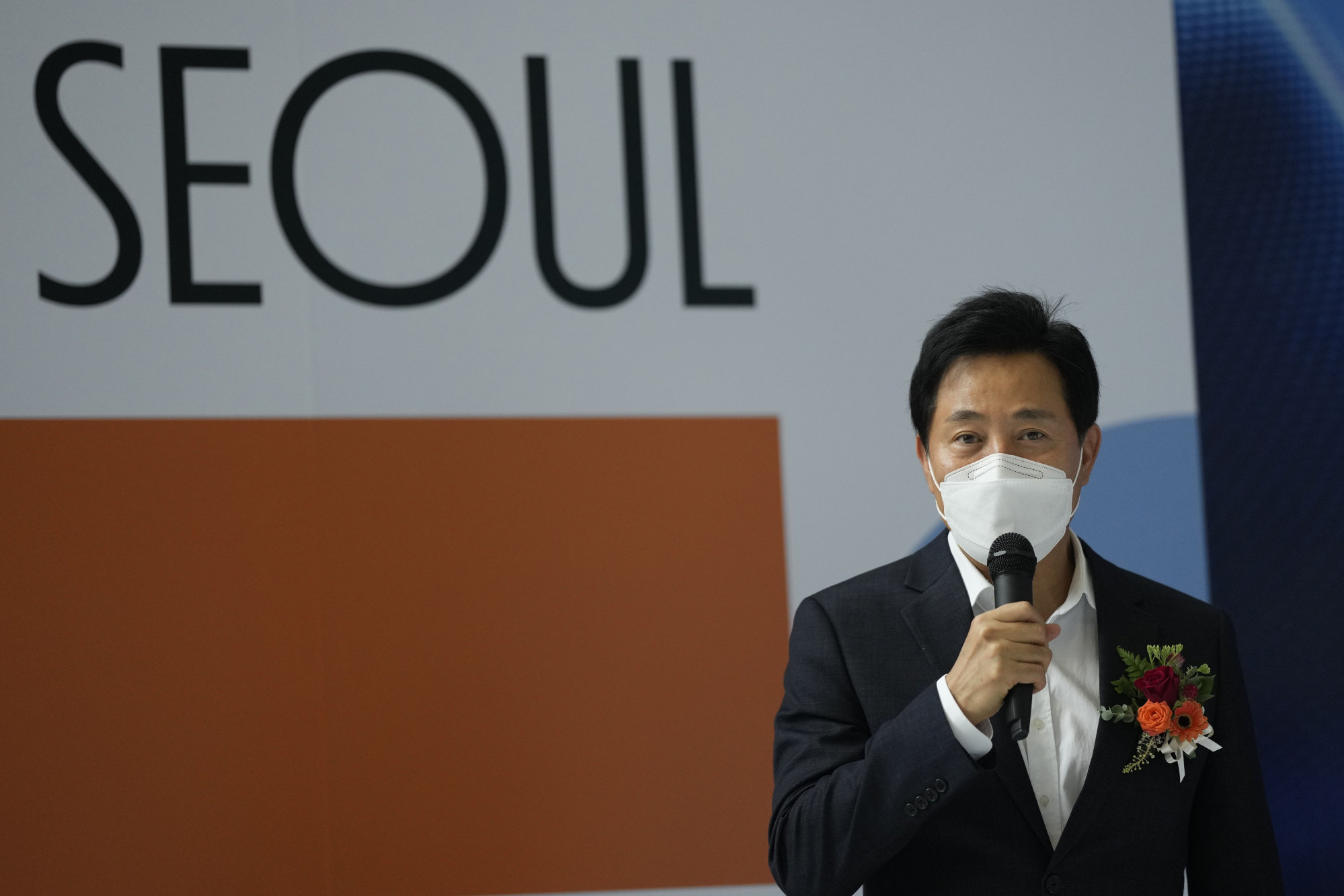

At a dinner on the Floating Island in Seoul’s Han River on September 3, the city’s mayor, Oh Se-hoon, proudly told guests about a recent Wall Street Journal article with the headline: “Seoul – Not Hong Kong – Is the Newest Art Capital of the World”.

“It was my master plan to make us the cultural hub of Asia by 2030, but we have already seen this come to light,” he said at the VIP event hosted by the city government in honour of the first Frieze art fair held in Asia.

Frieze, the London-based international art fair organiser, is a major player in an industry estimated by Arts Economics, a research firm, to have accounted for US$10 billion (HK$78.5 billion) in art sales in 2021.

The launch of Frieze Seoul, which has signed a six-year contract with the COEX convention centre, is being heavily promoted as a marker of maturity and confirmation of the South Korean capital’s potential as an international art trading centre, just as Art Basel did for Hong Kong when it arrived in 2013.

Over 70,000 people visited Frieze Seoul, which ran from September 2-5, to see a wide range of contemporary art presented by 110 galleries that included some of the biggest dealers in the world.

You cannot argue with the artistic practice here. The foundation has been strong for a long time

Sales were swift according to participants, with Belgian gallery Xavier Hufkens selling out their solo presentation of works by Sterling Ruby, priced between US$375,000 and US$475,000, and Kukje Gallery selling a painting by Park Seo-bo in the range of US$490,000-550,000 in the first hours of the fair’s September 2 preview.

Major international gallery Hauser & Wirth said it placed several works with South Korean collections, including a 2022 George Condo that sold for US$2.8 million and a Mark Bradford which sold for US$1.8 million.

In addition to the four-day Frieze Seoul, South Korea’s longest running contemporary art fair, KIAF Seoul, opened at the same venue with 164 galleries participating.

Pat Lee, the director of Frieze Seoul, thinks Korea’s rich art history and long tradition of art appreciation lends substance to the country’s art market ambition.

“The history of our country’s contemporary art scene is fairly short, but things happened so quickly,” says Lee. “I remember when Massimiliano Gioni came to direct the Gwangju Biennale – the oldest [art] biennale in Asia – in 2010, as it was the first time [a large number of art people came to South Korea].”

“You cannot argue with the artistic practice here. The foundation has been strong for a long time,” says the former executive director of Gallery Hyundai, one of the leading galleries in the country.

Even before K-pop and K-drama took over the world, Korean art and art practitioners had had much success abroad, he adds.

A younger generation which frequents Seoul’s many public and private art museums, such as the Leeum Museum of Art, has also appeared in the last decade, he says.

“When I started as a curator and gallerist in Seoul in 2002, there weren’t a lot of foreign galleries to introduce in our scene, as well as a lack of domestic galleries that were featured in global art fairs like Art Basel,” recalls Emma Son, senior director of Lehmann Maupin, an international gallery which opened a gallery in Seoul in 2017 and closed its Hong Kong gallery in 2020.

Lehmann Maupin, based in New York, is one of a handful of world-class galleries that have set up a permanent space in Seoul, along with Thaddaeus Ropac, Pace Gallery and Perrotin, the latter being the first Western gallery to open a permanent space in the South Korean capital since 2016.

We have a system that excessively concentrates on buying art to make profit

Rachel Lehmann, co-founder of the New York gallery, has visited South Korea about 50 times, Son estimates, ever since her visit in 1997 to see artist Do Ho Suh’s studio.

Pace Gallery is another American-based gallery that’s been in Seoul for a while, and it hosted a party at the opening of its second space in Itaewon last week.

The gallery’s CEO, Marc Glimcher, also thinks that the country has had a “mature art scene” for some time now. “South Korea has been ready for us for a long time. It’s just that the art world is still learning how to be global, as it’s a relatively new development.”

“For us, it’s where our artists want to have their shows, and South Korea is such a vibrant art community that’s also widely known for being a leader in new media and culture.

“It’s an extremely attractive place, not to mention that there’s a feeling of stability in its political administration so we don’t have to worry about any dramatic political changes that can disrupt the cultural world,” he says.

It’s this celebrity influence and the power of social media that has made visiting a gallery or museum a trend among young Koreans. Song Mino of K-pop boy band Winner had his own artworks featured at London’s Saatchi Gallery in 2020.

Not everyone is thrilled with the intensely money-driven vibe that a major international art fair brings to the city.

In a recent interview with the Post, Korean-born artist Haegue Yang says there is a sense of the “hysterical” in the way the international art world has embraced the Seoul market. “The art world has this aspect which I call ‘the attack of grasshoppers’,” she says.

Park Jeong-soo, founder of Jeongsu Art Centre in Seoul’s Samcheong-dong gallery district, is concerned that there is too much of a focus on art as an alternative investment asset rather than on the essence and intrinsic value of art.

“We have a system that excessively concentrates on buying art to make profit,” he says.

As for members of 143km, a cohort of graduate students at the Korea National University of Arts, Frieze Seoul is a grim reminder that “artists who don’t have a lot of marketability don’t get the same amount of attention as some of the big names in the scene”.

“Because the niche topics and distinct personality of our works, all of us make art that’s not commercial like the works shown at big art fairs,” says Choi In-yeong, one of the chief organisers of the project. “To show our art to a more diverse crowd, we decided to hit the streets of Seoul during Frieze week.”

Crowdfunding to borrow a 3.5-ton LED billboard truck to display video works from 28 artists, 143km circled around the COEX convention centre in Gangnam – the venue of Frieze Seoul – and South Korean galleries at Samcheong-dong.

They ended their project with a disco-themed party at a run-down building that was attended by fellow artists, art journalists and even representatives from Frieze.

“We think that the main goal of an art fair is not necessarily to sell art, but to meet new people and to create new dialogue,” says Judan Lee, another organiser of the project.

Anne Alene, a specialist art travel adviser who plans trips for patrons of leading institutions such as the Guggenheim and Tate museums, says Seoul is not the easiest city to navigate for non-Korean speakers.

“Wi-fi accessibility is very good, but Google Maps doesn’t exactly work here, and English doesn’t exactly work with the taxi drivers.” Other foreign visitors who came for the fair shared stories of being late to events due to communication errors and traffic jams.

Even so, in a country that claims to have the highest number of collectors per capita in Asia, more than 450 registered galleries and 78 art fairs last year despite the pandemic (compared to just eight in 2005), Lee says the future is bright.

“Frieze coming at this stage is really a validation of the strength of this ecosystem that has been developing over time.”