Review | An ‘Orwellian nightmare’ in Xinjiang – how China concocted an Islamic terror threat of its own

- China conveniently created the narrative of a Uygur Muslim terror threat in Xinjiang after 9/11, a sceptical Nick Holdstock writes in China’s Forgotten People

- Updated edition covers mass internment of Uygurs since 2014, when documented terror attacks occurred, and the world’s largely indifferent response

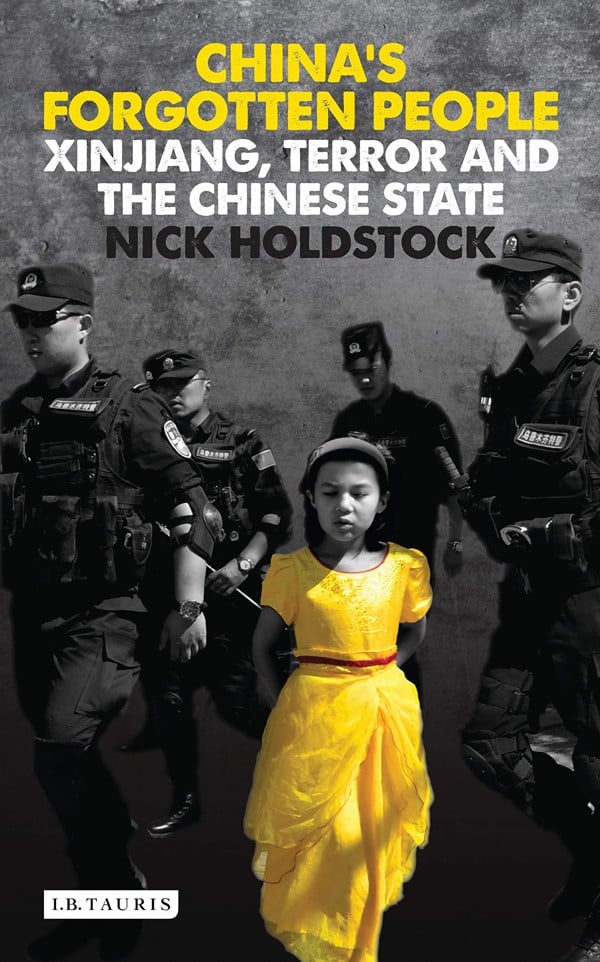

China’s Forgotten People: Xinjiang, Terror and the Chinese State, by Nick Holdstock, I.B. Tauris, 4 stars

When the Chinese government declared itself a “victim of international terrorism” a month after the September 11, 2001, attacks in the United States, it should have come as no surprise, according to veteran author and journalist Nick Holdstock.

“At first glance they had all the key ingredients necessary to make such a claim: a string of violent incidents linked to a Muslim ethnic group concentrated in a region close to Pakistan and Afghanistan,” Holdstock writes in China’s Forgotten People: Xinjiang, Terror and the Chinese State.

Holdstock cites an official Chinese white paper published in January 2002 used to strengthen its argument. Titled “East Turkestan terrorist forces cannot escape with impunity”, the document claimed more than 200 terrorist incidents had taken place inside the restive Xinjiang region of northwest China between 1990 and 2001.

But Holdstock is sceptical of these claims, finding the government’s timing too convenient and “many inconsistencies and questionable assertions” in its report. He believes this was a turning point that “helped to establish the narrative of a Uygur terrorist threat” in Xinjiang.

Holdstock’s revised version of his book, originally published in 2015, is a complex tapestry of geopolitical reportage and cross-cultural observations, and was updated to include recent developments in Xinjiang, where an estimated one million people from ethnic minorities have been interned in re-education camps, and the plight of the region’s Uygur people, Turkic-speaking Muslims who are its biggest ethnic minority.

No group claimed responsibility for the attacks, but the perpetrators were identified as Uygurs. Holdstock writes that while the attacks indicated an escalation of organised violence, not enough was known to draw a conclusion. “Though the Chinese government often names those it holds responsible for such attacks, it usually only does so if the alleged masterminds are already dead.”

Independent confirmation of the government’s allegations is difficult “mainly because of the severe restrictions on reporting in Xinjiang: access to local communities is hindered by obstruction and harassment by local officials and security personnel. A further obstacle is that for many Uygurs talking to foreign reporters can have serious consequences.”

Holdstock writes that the main issues facing Uygurs are settlement by Han Chinese, economic deprivation, religious and cultural repression, and family-planning policies, “Some or all of these grievances may have made someone throw explosives from a moving vehicle, or stab an elderly imam to death. But often we are just guessing. If we don’t know the causes (and in some cases, the details) of violent confrontations between Uygurs and the state, then the basis on which we regard them as being connected incidents is also questionable.”

Still, he adds: “If recent violent incidents in Xinjiang follow any pattern, it’s one where a local grievance triggers the anger of a community, whose members then quickly organise a protest (or riot) at a police station or government building, leading to clashes with security personnel.”

Whatever the case may be, events have escalated rapidly since 2014.

As of this year, more than 180 internment camps throughout Xinjiang are estimated to be holding 10 per cent of the region’s population, nearly a million Muslims. News of the camps started filtering out in late 2017. Despite satellite images and witness accounts, the Chinese government denied their presence for a year. By August 2018, a United Nations human rights panel triggered an international alarm when it concluded that Xinjiang Muslims were “being treated as enemies of the state based on nothing more than their ethno-religious identity”.

Holdstock argues that Beijing has long believed the non-Han Xinjiang region must be tightly controlled: According to Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region chairman Shohrat Zakir, the camps were set up to “get rid of the environment and soil that breeds terrorism and religious extremism”. China’s ambassador to the United States, Cui Tiankai, argues that Uygurs and other Muslim minorities are being turned “into normal persons [who] can go back to normal life”.

In January 2019, the Chinese government allowed international reporters into selected camps. Singing “If you’re happy and you know it clap your hands”, a classroom of brightly costumed inmates greeted the journalists. One internee told the journalists: “Before coming here, my brain was simple, my ideas impoverished. Now my brain has been enlightened with knowledge.”

If we don’t know the causes (and in some cases, the details) of violent confrontations between Uygurs and the state, then the basis on which we regard them as being connected incidents is also questionable

Holdstock writes: “The version of the camps that the government offered for scrutiny was misleading, but its distortions still implicitly conveyed their core idea, namely that Uygur culture, language and religious beliefs are of little worth and need to be corrected.”

He goes on to say: “While the Chinese state has targeted the whole Uygur population with surveillance and the threat of detention, there has also been a selectivity to the detentions that betrays their real intent. More than a hundred Uygur academics, artists and intellectuals have been detained since 2015.”

Many were well-known figures: Halmurat Ghopur, a former president of Xinjiang Medical University Hospital, is now a “separatist” handed a two-year suspended death sentence; Rahile Dawut, a famous Xinjiang anthropologist and folklorist, has been missing since December 2017.

In early 2015, most Uygurs could still visit their local markets and frequent weekly prayers, and communications abroad to friends and relatives remained open. But by November 2016, exit visas had become practically impossible to obtain. Xinjiang residents were required to hand in their passports for “safekeeping”. In Xinjiang’s southeast, GPS trackers were fitted to all cars.

Inside the camps, Holdstock describes an “Orwellian nightmare” of interrogations, indoctrination, constant surveillance, sleep deprivation, beatings, barbed wire, bright lights, and stale food.

Two years since the camps opened, there are signs of change to the Xinjiang policy. Newly released Kazakh inmates are being put to work in clothing and textile factories for 12-hour shifts for little pay, and are required to endure ongoing “political education”. Those who refuse to sign the employment contracts are sent back to the camps.

Arundhati Roy’s essays on 20 years as a thorn in India’s side

Before the camps, few outside China identified Xinjiang with Islamic terrorism. Now it is in the international spotlight as a region beset with human rights atrocities. Global awareness has never been greater. “While this is no doubt a good thing, it hasn’t translated into much conspicuous action from other countries,” Holdstock writes. “Most Western powers have done little more than express different flavours of ‘concern’ (‘grave’, ‘strong’, ‘intense’).”

The author’s admiration for the Uygurs’ adaptability and resilience shines through in his book. While he can move quickly back and forwards in time and place and keeping up can be tricky sometimes, China’s Forgotten People is a more than valiant endeavour.