Thin line between apes and humans

As cinema's great simian saga adds a new episode, Mathew Scott looks at the socio-political issues that fuel Planet of the Apes' appeal to audiences

To fully appreciate the impact first had, it helps to look back to the turmoil throughout the world in 1968.

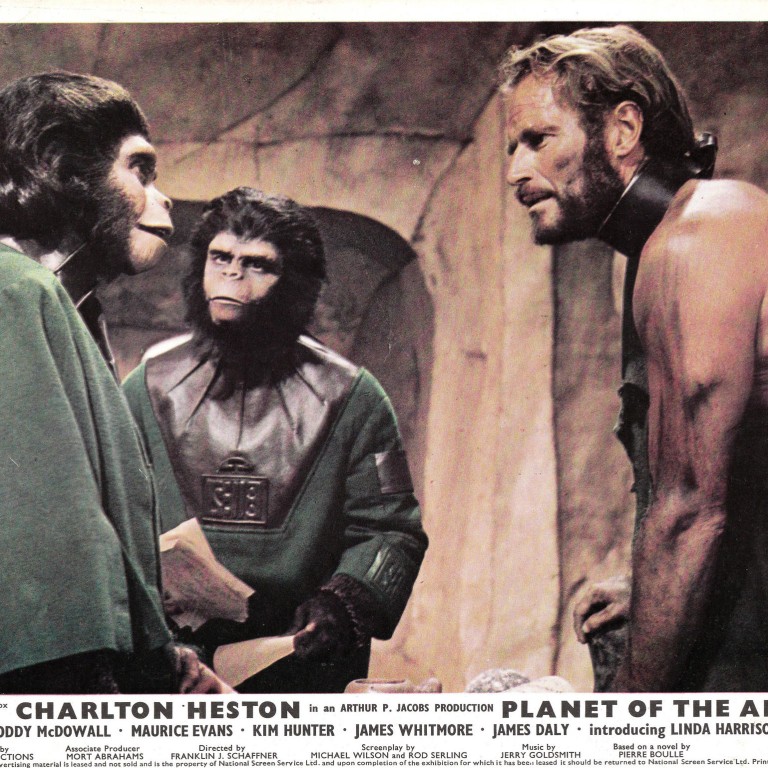

When director Franklin J. Schaffner launched the original franchise - presenting box office hero Charlton Heston, embodiment of the all-American man, as an astronaut who stumbles on to a planet that is strangely familiar - the Vietnam war was still raging, while the civil rights movement had gripped America and shaken that nation into facing up to issues of freedom and basic human rights.

“I was struck by how these films were about violence, fear, hatred and oppression, but also about the struggle for forgiveness, the importance of compassion and the necessity of taking risks to side with the vulnerable.”

In many ways, the world as people had known it was being turned upside down and for the studio heads at 20th Century Fox, Frenchman Pierre Boulle's 1963 novel provided a temptation too great to ignore. The fantastical story was designed to force its audience to question man's place on this planet and was tweaked first by one of the masters of the macabre, 's Rod Serling, before Michael Wilson - the once-blacklisted writer behind (1946) and (1951) - was brought in to fine-tune things.

The original budget had crept towards what was in 1968 an incredible US$6 million - but the money (which mostly went towards John Chambers' ground-breaking make-up designs) proved well-spent. The filmmakers had conjured up an imagined world that was frightening because it was so believable, backed by a razor-sharp script and impassioned lead performances (as humans and as apes) that dared the audience not to believe.

The film collected an estimated US$32 million from the box office and thrilled audiences despite a number of critics looking down their noses ("It is no good at all, but fun, at moments, to watch," said ).

And then there were the themes explored by that first film, and by the novels, television series, comic books and reboots - the latest being , which is released on Thursday - that have been developed from it since. For California-based civil rights activist Eric Greene, author of (1998), the impact the original films had on him as a youngster were immediate and the issues they forced him to address still resonate today.

"I was struck by how these films were about violence, fear, hatred and oppression, but also about the struggle for forgiveness, the importance of compassion and the necessity of taking risks to side with the vulnerable," says Greene.

"The movies were visually exciting, colourful, had great actors of multiple racial backgrounds and emotionally engaging stories - often about hunted or endangered outsiders - but they had a strong moral core that always appealed to me. There was a great mixture of entertainment and depth."

“At a time when the American civil rights movement was transforming the United States, these movies celebrated heroes who conquered their fears, reached across racial lines, and fought for justice and equality.”

Greene says that during the course of his research, he found common experiences had been shared by audiences - the nurse who said she learned about caring for the vulnerable from watching Dr Zira (played by Kim Hunter in the original film), and other interviewees who said they had gained an understanding of how racial prejudice stemmed from the fear of something different.

"I think that's why they struck such a deep nerve with people," says Greene. "As an adult interested in how popular culture both reflects and impacts politics, I decided to research in more depth exactly how the films dealt with issues such as American racism, the war in Vietnam, the sense that Western political power was in jeopardy.

"At a time when the American civil rights movement was transforming the United States, these movies celebrated heroes who conquered their fears, reached across racial lines, and fought for justice and equality. That's a very strong message about what's truly heroic and admirable in the world."

The films have also been supported by what for the most part have been fully fleshed out and smart scripts, says Greene. "[It's] good storytelling, one of the oldest ways of conveying morals," he says. "As the sequels went along, they got even more political and more focused on racial discrimination as an issue. In the first films, for instance, the tension between religion and science, faith and facts was central. By the last two films, they were really focused on the issue of overcoming racial oppression and if we can live together in peace and respect after so much conflict and pain or if we're doomed to keep replaying the cycle of violence."

Agustín Fuentes is another fan of the original franchise and he spends his working days as professor and chair of the University of Notre Dame's department of anthropology. When tracks Fuentes down, he's just landed in Gibraltar for work on primate research and fittingly has ' more weighty issues on his mind as he makes plans to take in in the near future.

"People want to know what it means to be 'human' and, subsequently, the apes - those beings so closely related but not quite us - fascinate us," he says. "Some philosophers, many scientists, and much of the public consider that an answer to what humans are at our core might lie in the behaviour of the apes: that possible insight into human nature can be had via our closest evolutionary relatives. This may be true, but it is not so simple as that."

The films present - through the ape characters - various sides of human nature: Cornelius (Roddy McDowall) = good; Dr Zaius (Maurice Evans) = bad. But Fuentes believes this is an over-simplified view "that both obscures the differences between humans and other apes and denies other apes their own 'openness' as a valid way of being - they make the mistake of seeing them not in their own right but on a trajectory towards humanity," he says.

Since the release of Charles Darwin's about 155 years ago, there has been a growth in the use of apes as models or mirrors for understanding human nature, says Fuentes. "In the movies, this view is clear: humans have reverted to savagery and beastliness, opening up a 'human' evolutionary space for apes to 'evolve' into. These 'evolved apes' seem to be on the same road to folly as the human species that they are replacing: the apes become human," he says.

But for all the intellectual debate has ignited in its various guises over the years, audiences have also been offered, for the most part, a high standard of pure entertainment.

"I think in 2011 was successful because it played into the love so many have for the original series, while updating it with the latest advancements in CGI. The films really have something to say about social injustices of the day. And they have talking apes."

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes