Five heirs of wealthy Asian families who invest in fighting climate change and pollution, and what they’ve learned

- Solar power projects, sustainable building materials, green bonds – wealthy millennials from Indonesia to Singapore to Hong Kong have embraced climate activism

- They’ve also incorporated good environmental practices in their family businesses

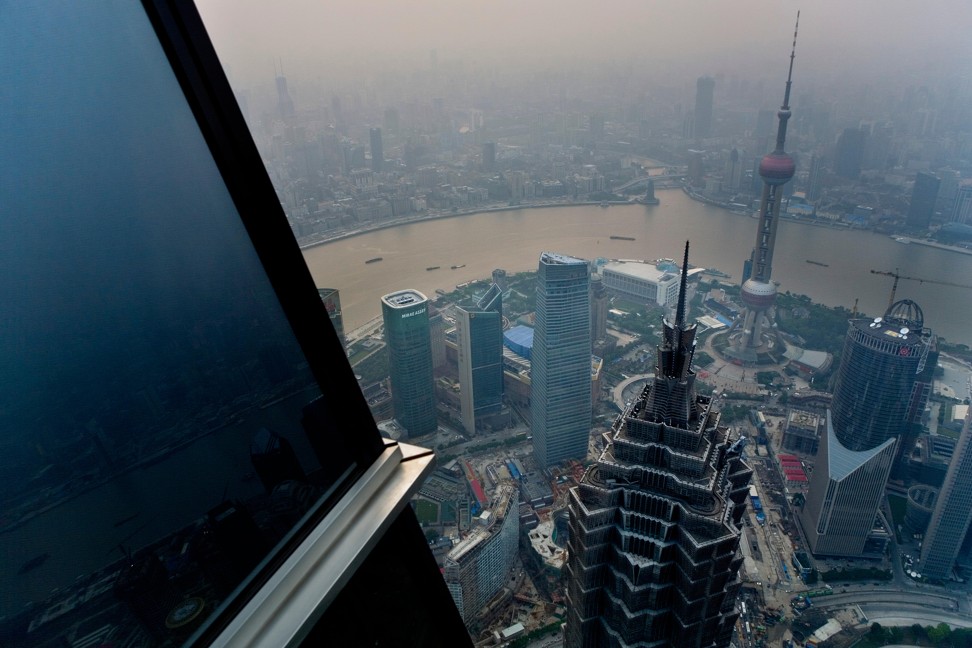

From Beijing’s gridlocked ring roads to Delhi’s urban sprawl, Asia is home to two of the planet’s five most-polluting countries, as well as more than one-third of its wealthiest citizens.

But government and philanthropic efforts to combat climate change often take a back seat to programmes aimed at fixing more immediate issues, such as alleviating poverty and lifting education standards.

Getting wealthy people around the world to contribute to philanthropic causes and deals is vital because few other groups have the money or flexibility to make an impact, while global attempts to combat climate change have been hobbled by competing national interests.

“Despite the recent international focus on climate change, the environment remains an area that receives relatively little support from foundations in Asia,” the Asia Centre for Social Entrepreneurship and Philanthropy said in a 2018 report. It added that Asia foundations are “only beginning to give along the line of international agendas”.

However, attitudes are starting to change as some of Asia’s biggest fortunes pass to a younger, more environmentally aware generation, and the climate crisis edges nearer to a point of no return. Cherie Nursalim, for example, considered herself somewhat of a “greenie” until she met her husband, Enki Tan, a board member of Conservation International.

“When I first got married he was saying ‘don’t use [more than one] tissue paper!’ and I thought ‘I’m marrying a monster!’” laughs Nursalim, who comes from the family behind Giti Tires, which employs more than 33,000 people globally, from China to the United States.

As well as offsetting carbon emissions from its factories by planting trees and reducing energy and water usage, Giti is adopting new technologies that help drivers maintain optimal air pressure in their tyres, reducing fuel consumption.

Much of Nursalim’s efforts go into convincing other companies and wealthy Asian families to introduce more climate-change philanthropy and core business measures through her membership of the Asian Philanthropy Circle and the leadership council of the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

“When you have people who are still starving, then that is the immediate thing, and it’s human nature that when it’s not right in front of you, you don’t act on it,” she says. “But I think all should know about it and do more within their own interest areas to help the cause.”

For Kathlyn Tan, diving on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef brought home the devastating effects of climate change. Rising sea temperatures had turned much of the natural wonder’s riot of colour into dull, bleached coral.

A relative newcomer to environmentalism, she is been looking for investments in sustainable building materials and solar projects in her role as a director at her Singapore-based family office Rumah Group. (She is also an executive at family-linked real estate developer GYP Properties Ltd.).

The standards in China are not really aligned with international standards, so I think that’s why some investors have difficulties finding green bonds that meet their criteria

Tan says many city dwellers in Asia would be willing to do more for the environment if they could see what’s at stake. She works with Project Aware and Coastal Natives, as well as a new venture that seeks to teach Singaporeans about the impact of man-made trash and climate change on marine life.

“A couple of years ago when we started talking to people it just didn’t seem like the focus, and it was more about health and sanitation and early childhood development,” she says. “But now it seems to be a really hot topic.”

But Asian investors wanting to help tackle climate change are navigating a landscape as murky as the skies above Jakarta. Pitfalls range from lax regulations and standards of what constitutes ESG (environmental, social and corporate governance), to “greenwashing” – bad deals given a veneer of environmentalism to attract altruistic lenders.

While green bonds used to finance climate-friendly projects such as solar power plants have taken off in the US and Europe – Moody’s Investors Service predicts the market will hit US$200 billion this year – they are still a relative rarity in most of Asia. When they can be found, there’s often a catch.

“There has been a lot of issuance coming from China,” says Yuni Choi, associate director for investment at Chen’s family office, RS Group. “But the standards in China are not really aligned with international standards, so I think that’s why some investors have difficulties finding green bonds that meet their criteria.”

However, it’s hoped that rising demand from investors, including the growing cohort of millennial heirs, will force Asian policymakers and exchanges to impose environmental, social and corporate governance rules and disclosure requirements, Choi says.

Robin Pho’s family earned its wealth supplying workers for the oil and gas rigs dotting the Indonesian archipelago. After some soul-searching and a course at Singapore business school Insead, he realised his passion lay outside the family business, and founded a solar-power provider called Right People Renewable Energy.

But as the company started installing solar panels on top of condos and warehouses, it quickly hit a funding bottleneck.

While banks would happily loan his clients money at low rates for traditional tools such as diesel generators, they would only lend at a higher rate for solar power set-ups. So to jump-start business, he has had to give money from his own family office for products, which customers typically pay back over three to five years.

While the projects have so far offered good returns, eventually he will need other family offices or institutions to step in to expand throughout the region.

A company that employs workers from a remote impoverished village sounds like a worthy investment, but questions emerge when it’s a carbon-intensive coal mine. To help navigate these and other ESG dilemmas, Singapore-based Tolaram Group has hired Edris Boey, who worked in the field at KPMG, to run ESG investing at the family’s Maitri Asset Management.

The family initially made its wealth from textiles, cereals and consumer goods and has morphed into a global group worth an estimated US$1.8 billion.

While the company will not reveal the details of its investment model and criteria, Boey has injected about 10 key questions into the list asked of every deal.

It’s the kind of formal ESG rigour traditionally missing from some Asian family offices. As it becomes more common, governments and companies will be pressured to start introducing and enforcing environmental rules.

“Everyone is concerned about how the business climate is going to be, and every country is saying ‘invest in me, don’t go anywhere else,’” she says. “In terms of when Asian family offices will really pick up on the ‘E’ element of ESG, it really depends on government regulations.”