How social media helps spread extremist content in Indonesia, and what’s being done about it

- Extremists and internet companies in Indonesia are engaged in a cat-and-mouse game to stop radical content spreading on social media

- While Facebook is improving its processes, its algorithm inadvertently recommends other radical links to users on extremist pages

Despite efforts to stem the tide of radicalism on social media in Indonesia, groups and individuals with extreme Islamist views continue to emerge on digital platforms, sowing seeds of intolerance and violence.

Groups and pages espousing extremism sprout up, find followers, and are deleted, only to reappear in a cat-and-mouse game with the government and internet companies trying to shut them out.

JAD: the extremist group that recruits families to spread terror in Indonesia

Social media users seeking such content do not have to try too hard if they are acquainted with keywords commonly used in the titles of extremist pages and groups.

The search function on Facebook, for example, identifies dozens of potential radical groups for users to connect with, recent research by the Post found.

Common keywords include “ghuroba”, meaning to feel alienated because of one’s adherence to “pure” Islamic teaching, and “tauhid”, referring to an Islamic concept of oneness with Allah.

Searches turn up pages and groups with names such as Generasi Ghuroba (Ghoruba Generation), Pemuda Ghuroba (Ghuroba Youth), Tauhid Harga Mati (Undisputed Monotheism) and Yuk Ngaji Tauhid (Let’s Study Tauhid).

Before it became inaccessible late last year, the Pemuda Ghuroba page boasted more than 1,400 likes, and carried content relating to radical teachings, jihad and the Islamic State militant group.

In November, Facebook said it had removed more than 14 million “pieces of terrorist content” on its platform so far in 2018 that promoted Islamic State, al-Qaeda and their affiliates.

The social media giant is using machine learning to assess posts – including pictures, videos and comments – that may signal support for the militant groups, it says.

“In some cases, we will automatically remove posts when the tool indicates that the post contains support for terrorism,” Brian Fishman, head of counterterrorism policy at Facebook, writes.

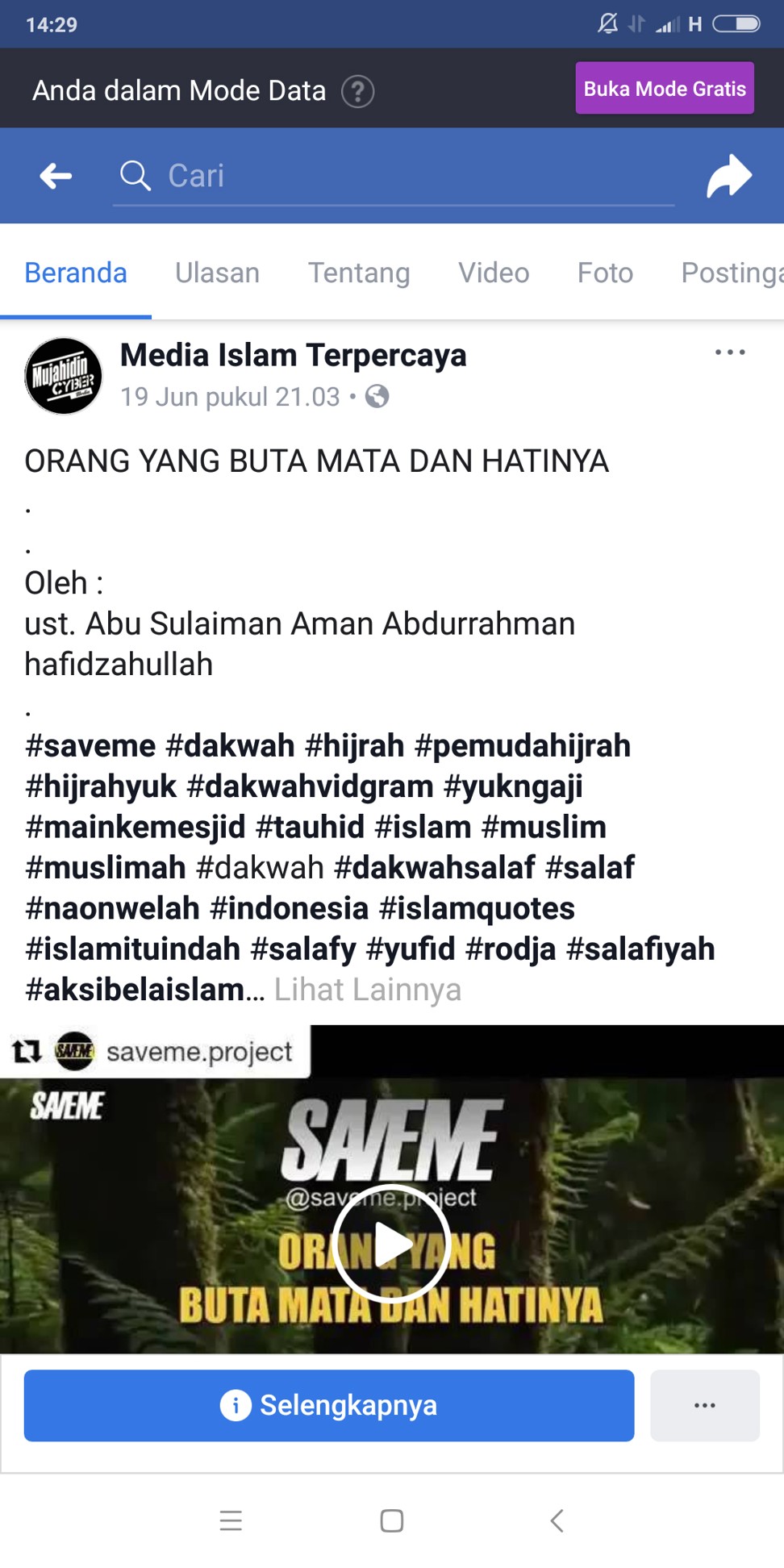

However, the company has its work cut out as these groups continue to crop up. And by applying algorithms intended to connect users to content they may find interesting based on previous behaviour on the site, Facebook inadvertently recommends other radical links on these pages to users. One recommended to this writer, Media Islam Terpercaya (Trusted Islamic Media), carried the text of sermons by Abu Bakar Bashir and Aman Abdurrahman, two radical clerics highly regarded by militants in Indonesia.

The Yuk Ngaji Tauhid page included a recorded sermon by Abdurrahman, who is on death row in Indonesia after being found guilty of inciting at least five terror attacks.

Shortly after we requested a media interview with the group’s administrators, the page became inaccessible.

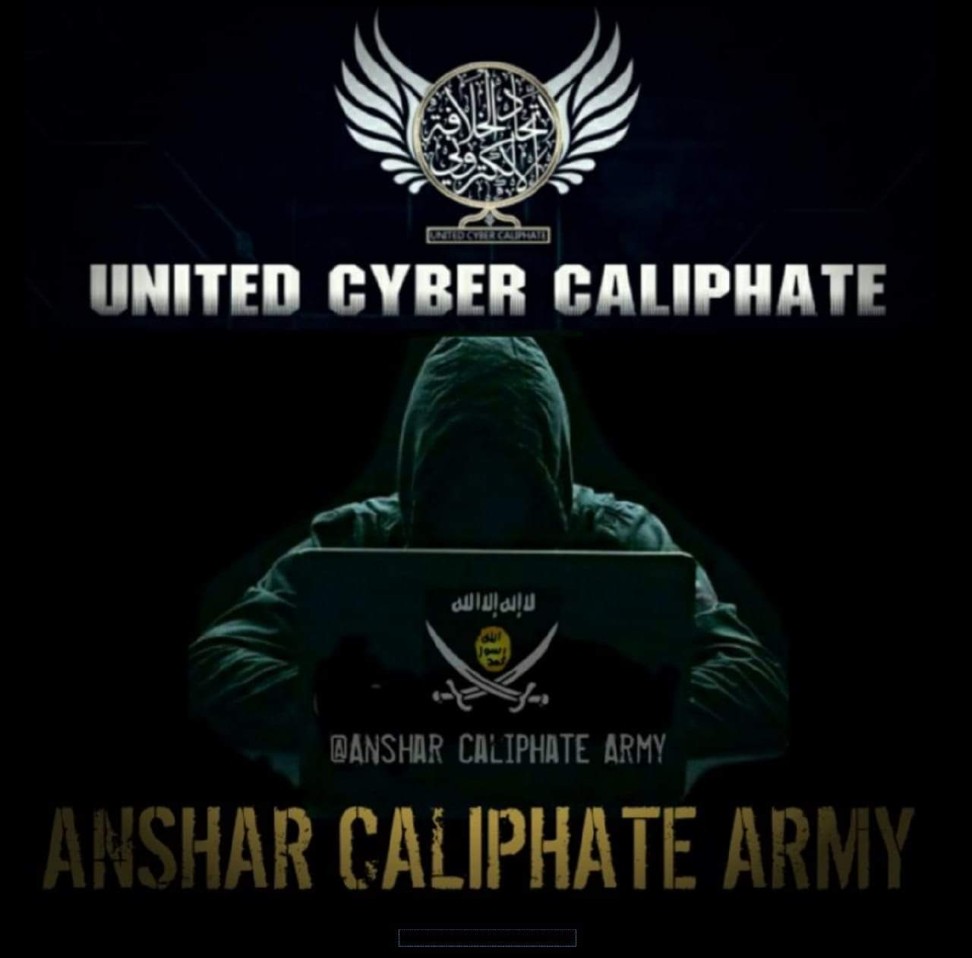

Two major producers of radical content in Indonesia are Gen 5.54 and Saveme Project. According to a report by the Jakarta-based Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict, Gen 5.54 emerged around October 2017. It creates a wide range of radical materials, from e-magazines to Android applications.

“It is unique because, until then, most original content in Indonesia had taken the form of text or audio … Gen 5.54 is much more creative and technologically skilled,” says the report, titled “Indonesia and the Tech Giants vs ISIS Supporters: Combating Violent Extremism Online”.

Published in July 2018, the report reveals that groups associated with Gen 5.54 had been banned by the Telegram messaging service in May last year, and the group’s Android app became inaccessible around the same time.

At the time of publication, videos posted by the group were still live on the video-sharing platform Vimeo.

To all FB friends, is there anyone who sells bombs? I want to buy

The Saveme Project, which emerged in 2018, produces original videos that it posted on Instagram, YouTube and Telegram before its accounts were blocked.

Some radical Facebook users have commented about how the company has blocked their account, but boast that they are still able to post because they have an active duplicate account.

Estimates put the number of Facebook users in Indonesia as high as 130 million. But in a financial report a year ago, the company stated that Indonesia is one of a few countries in the developing world where a large number of users have fake or duplicate accounts. This would allow users with radical views to operate away from the prying eyes of their regular social circle.

An account with a profile picture of a woman going by the name Ummu Azka – of which there are scores on Facebook – frequently posted radical content.

Azka’s Facebook wall shows that she began “hijrah” – a shift to becoming increasingly religious – in January 2018, when she began to express extreme views. Before long she was asking “friends” an incendiary question.

“To all FB friends, is there anyone who sells bombs? I want to buy,” she wrote on November 15.

When her sincerity was questioned, Azka insisted she was serious and explained that she wanted to “bomb the infidels”.

“I’m tired of life,” she added.

Another “friend” suggested she could make her own device using instructions found on YouTube.

Azka last posted on November 27. It was an illustration of a cartoonish human figure with the “Gen 5.54” logo for a head, throwing what resembled Indonesia’s national symbol, the Garuda, into a rubbish bin.

It was accompanied by the words “Buanglah si Taghut pada Tempatnya”, meaning throw away that which is worshipped or obeyed other than Allah – the image implying it was a reference to the government. The post sparked a debate, with more than 300 comments.

Chat-based apps such as WhatsApp also play a role in connecting extremists. The Facebook page of a group called Sayap Merah contained links for users to join WhatsApp chats with up to 60 Islamic State sympathisers.

An administrator of Sayap Merah told the Post that the purpose of the group was to “gather Islamic people to share knowledge and strengthen unity”.

As many as 85 per cent of those convicted say that from the time they were first exposed to [materials about] Islamic State to them committing an act of terror was less than one year

At least 10 uploads, in the form of photos, videos and radical narratives, were posted daily on the page. On this writer’s first day as a group member, the latest post was a Gen 5.54 poster.

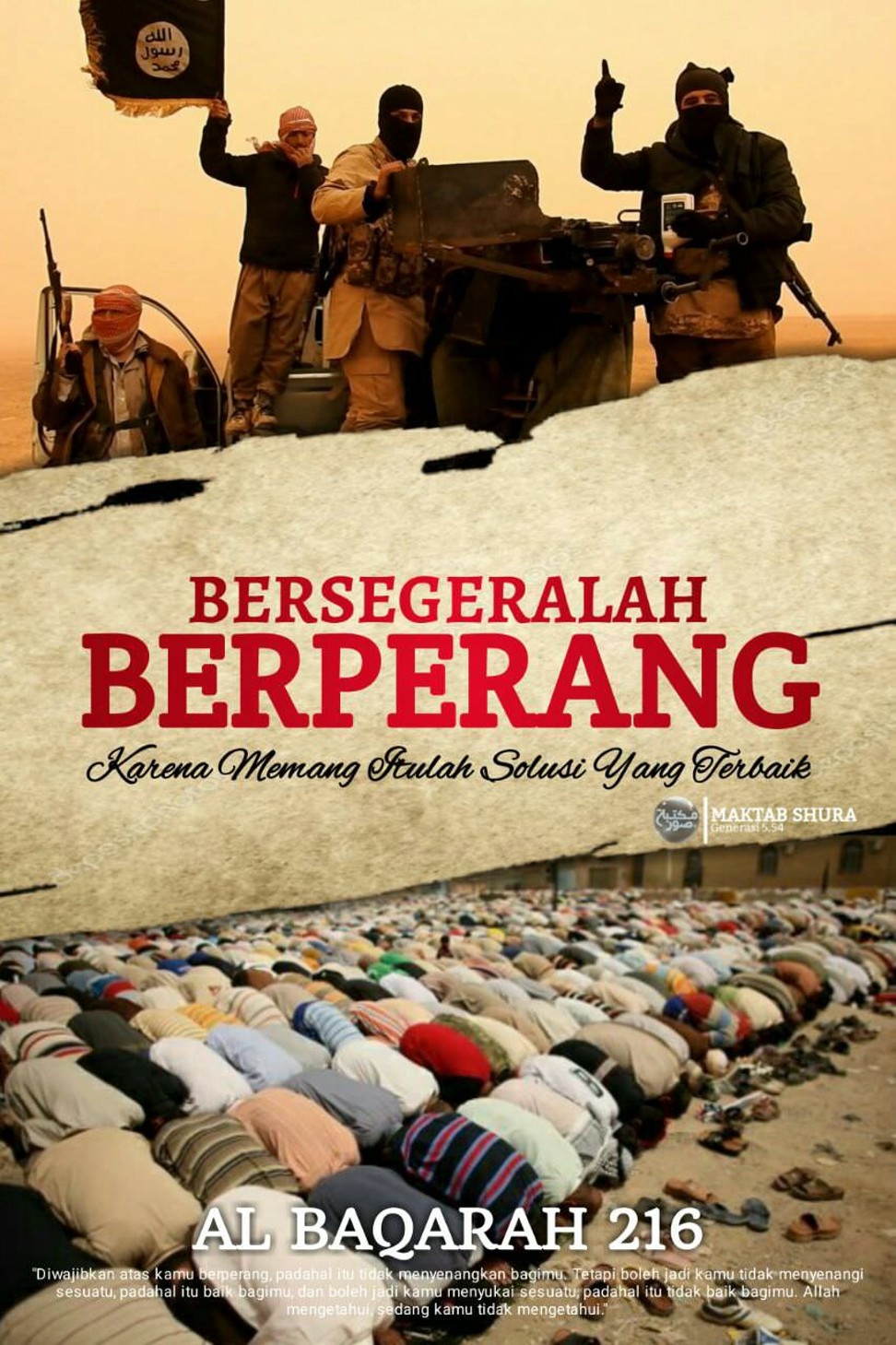

“Hurry and fight because that’s the best solution,” it read, with a photo of the Islamic State flag, members holding weapons, and verses from the Koran exhorting followers to fight.

(It is believed that instructions in the Koran for Muslims to fight “idolaters” and “unbelievers” originally targeted those who led a backlash against the Prophet Muhammad in Mecca during his lifetime.)

Several recent studies highlight the role platforms such as Facebook and Twitter can play in radicalising young Muslims. One in particular, by terrorism expert Dr Solahudin from the University of Indonesia, reveals a disturbing trend.

Solahudin interviewed 75 convicted terrorists in Indonesia in 2017 and concluded that social media was acting as an agitator and hastening the radicalisation process.

“As many as 85 per cent of those convicted say that from the time they were first exposed to [materials about] Islamic State to them committing an act of terror was less than one year,” he writes.

Solahudin adds that those vulnerable to being influenced by extremists are exposed to numerous narratives and violent content on social media on a daily basis.

Before the widespread use of social media, it would take between five and 10 years for a newly radicalised individual to take part in a terror attack, Solahudin writes.

According to the academic, terrorist groups radicalise others primarily by sharing narratives that describe the supposed pleasures of life with the Caliphate – or Islamic State – and sharia law. They also position Western countries as the enemies of Muslims.

The Indonesian Ministry of Communication and Information Technology (Kemkominfo), along with tech giants including Facebook, are intent on countering extremist views on social media.

Contact details and platforms are provided for reporting extremist content, and accounts and uploads related to radicalism are blocked when they are found. Kominfo provides complaint services through the portal Aduankonten.id and @aduankonten on Twitter.

In November, a delegation of nine countries including Australia, Malaysia and Singapore met in Jakarta to discuss counterterrorism efforts, including cooperating with social media companies to block users who share harmful content.

“Not only the government, but also social media, the private sector, Twitter users, Facebook users and internet users, all have the same responsibility to fight terrorism,” said Wiranto, Indonesia’s coordinating minister for politics, law and security, to delegates.

Indonesian mosques found spreading radicalism to government workers

Facebook says its new machine learning tools have reduced the length of time terrorist content reported by users remains on the platform: from 43 hours in the first quarter of last year to 18 hours in the third quarter.

It will also continue to improve its technology to detect and prevent the spread of content that is aimed at encouraging terrorism.

“Terrorists are always looking to circumvent our detection and improvement with technology, training and process,” Fishman wrote.