How Singapore can renew ethnic neighbourhoods without losing their traditional character

The Lion City is known for its traditional ethnic neighbourhoods such as Little India, Chinatown and Kampong Glam. It plans to renew these areas while retaining what makes them special, and gentrification is not on the cards

Singapore’s traditional ethnic neighbourhoods, including Chinatown, Little India and Kampong Glam, offer a look at the diversity of Asian cultures in a single city. However, the enclaves are under pressure as rent increases threaten to squeeze out traditional family businesses.

That’s why Singapore’s Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) has been working with members of these communities with a view to preserving both their commercial viability and the authentic heritage of the neighbourhoods.

“The government’s plans to re-envision Kampong Glam, Little India and Chinatown is part of the urban renewal process for the historical parts of Singapore,” says Nicholas Mak, head of research and consultancy at SLP International Property Consultants. He adds that this does not mean gentrification.

Chou Mei, group director for conservation and urban design at the URA, agrees, and says the principle of conservation in Singapore is not about freezing a building in its past, but allowing it to have continued relevance and use in today’s context.

The traditional home of Singapore’s Indian community, Little India, has long had a reputation for being one of the city’s more unpolished and authentic neighbourhoods. With its carefree disarray – unlike other parts of the city state – it is often thronged with multi-ethnic crowds.

The area suffered a blow to its reputation in 2013 following the country’s first riot in 40 years, when a mob of hundreds hurled bottles and rubbish bins after a bus knocked down and killed an Indian migrant worker in the neighbourhood. Stricter surveillance and crowd control measures have since been in place.

We still have our traditional businesses and new businesses to keep this area relevant and keep people coming. If we all have just traditional businesses, then it becomes a fabricated place and we will lose our relevance to society

The Centre for Liveable Cities report, published in May 2017, outlined the need to balance practical realities, social tension and the interests of stakeholders in Singapore’s ethnic districts.

One area highlighted was the preservation of vanishing trades in the district, including henna art, Ayurvedic clinics and sari stores.

Preservation efforts have therefore included the creation of demarcated areas for these fading trades and awarding of grants to encourage their revival.

“Every Indian in Singapore or every Singaporean who wants to buy spices … they still have to come to Little India. And this is what is really keeping this place vibrant,” says Rajakumar Chandra, who chairs the Little India Shopkeepers and Heritage Association.

Some agree that Little India’s allure is its ability to tread the fine line between community interests and commercial aspirations.

Another part of town, Kampong Glam – also known as Arab Street – brings a taste of the Middle East. The area has had an extensive makeover since 2003. Cafes, boutiques, upscale restaurants, and spaces for the arts and heritage have sprung up alongside the traditional shops and stalls selling souvenirs, textiles, carpets and handicrafts.

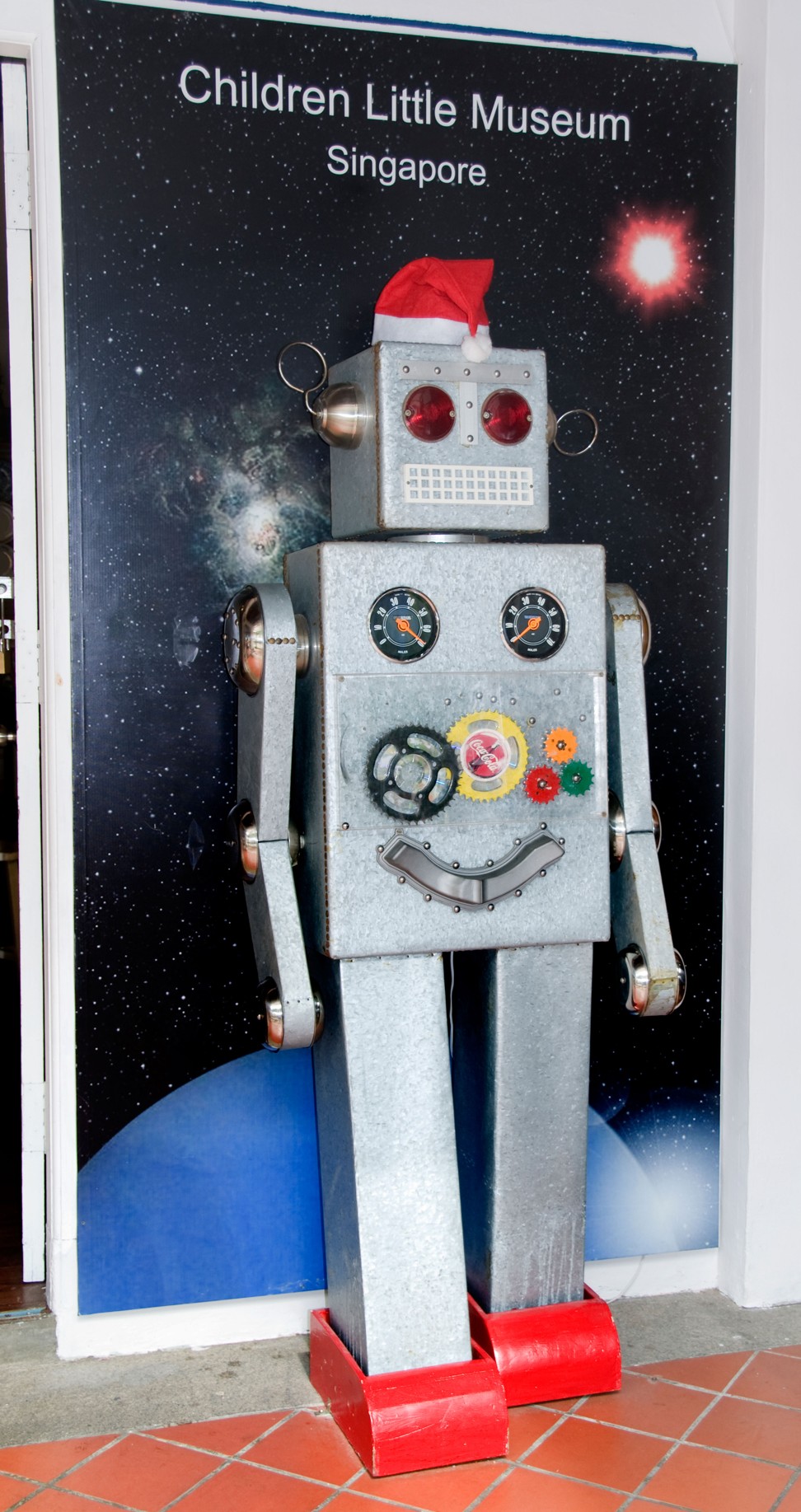

New developments such as the Children Little Museum and the Vintage Cameras Museum have also helped lend the neighbourhood a quirky, arty touch.

The report from Centre for Liveable Cities stated, however, that despite efforts to increase footfall, a number of shops have closed on Arab Street in the past three years.

To inject vibrancy into the neighbourhood in recent years, the One Kampong Glam business association, Aliwal Arts Centre and Malay Heritage Centre have hosted more live art and cultural festivals, such as the Aliwal Art Night Crawl, which featured Malay cultural dance performances, silat martial arts shows and community yoga.

One Kampong Glam founder and chairman Saeid Labbi, recognising the area’s serious traffic congestion, initiated regular weekend car-free zones that have even led to it hosting more soccer games.

Labbafi says businesses are conscious of the area’s heritage. “Many other historical places have lost their old trades or their businesses,” he says, adding: “We are hoping that the remaining businesses in the area work towards conserving their history.”

Business owner and co-founder of the Black Hole Group of lifestyle brands, Calvin Seah, says: “We still have our traditional businesses and new businesses to keep this area relevant and keep people coming. If we all have just traditional businesses, then it becomes a fabricated place and we will lose our relevance to society.”

More community festivals have been held to enliven the areas. Pop-Up Noise: Soul Searching saw 31 artists tackling issues including memory, preservation and space usage in the Chinatown vicinity in October 2016.

Nightly shows have also been introduced in Kreta Ayer Square during Chinese New Year celebrations featuring cultural performances, festive dances and New Year music. Whether it’s rediscovering local history or engaging with communities, art and culture have been successful in revitalising pockets of Chinatown.

In recent years, the walls of buildings along Tanjong Pagar Street have been brought to life with colourful murals, many evoking traditional scenes and symbols, including the nutmeg plant, referencing the neighbourhood’s past as a nutmeg plantation.

Two pianos have been installed at the Tanjong Pagar Centre to create a public space for music lovers to exchange ideas, share their love for music and practise.

The government has taken different approaches to developing the traditional neighbourhoods.

He adds that not many Singaporeans know these places well because they have no reason to go there.

“These places are not part of their everyday life. For example, the Chinese community used to go to Kreta Ayer at least once a year in the past, to buy New Year goods. These days, one can buy New Year goods everywhere, even online. The critical question that we have to ask ourselves is how can we make these places relevant to our own people,” Yeo says.

“How can we attract younger people to a place without the ‘ills’ of gentrification? We want some new trendy, hipster joints to attract a new group of users, so that they can have their own memories of the place. But, how much is enough? This brings us back to the question of where the tipping point is.”