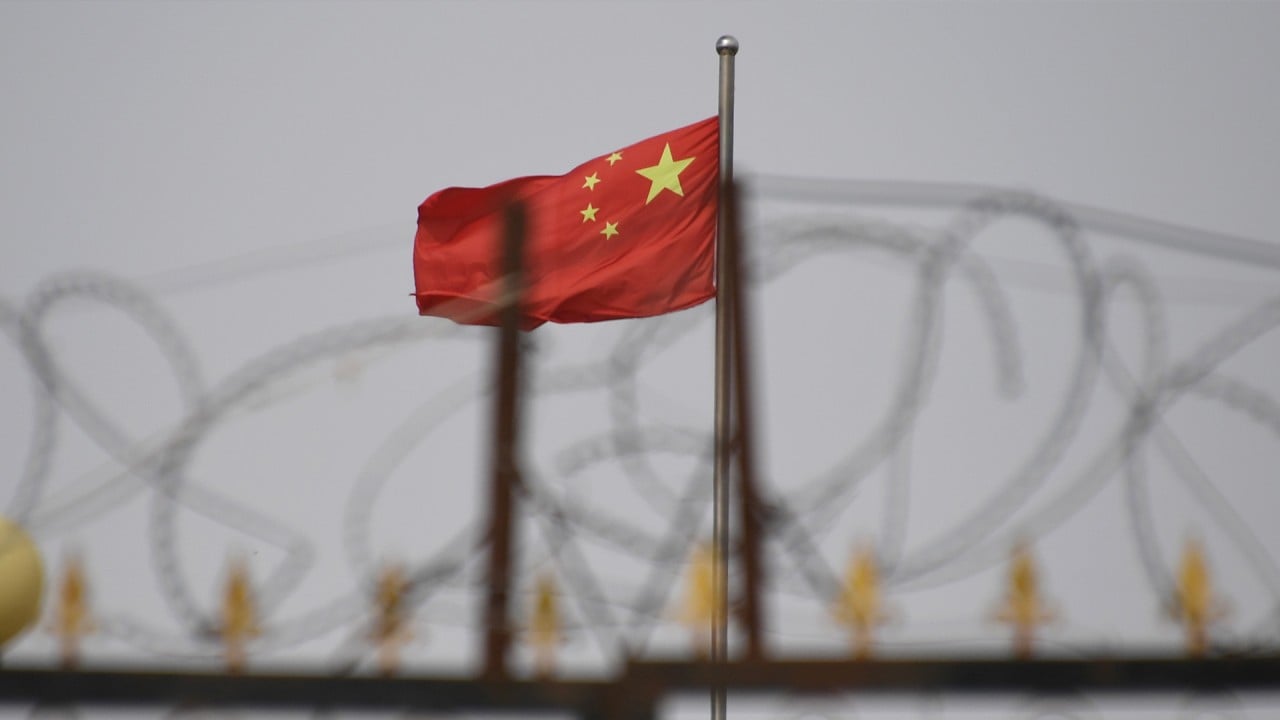

China’s Xinjiang gets money, talent from ‘pairing assistance’, but is the controversial programme helping?

- Beijing says that Xinjiang’s people, especially those in ethnic minority groups, benefit from the initiative, which has brought trillions of yuan to the region

- But the US Department of State says billions in pairing-assistance funding has been used to build factories where alleged labour abuses take place

This is the second in a series of stories looking at China’s Xinjiang province and how the far-western region is coping economically under a series of US sanctions over alleged human rights violations and the widespread use of forced labour.

The idyllic setting – including snow-capped mountains, lush forests and wide-open prairies covered in flowers – makes the autonomous region appealing to the country’s growing middle class and wealthy tourists. It has also helped boost public support for Beijing’s “pairing assistance” initiative, intended to bring resources and prosperity to the far-western region.

03:36

Beijing hits back at Western sanctions against China’s alleged treatment of Uygur Muslims

What is ‘pairing assistance’?

Besides Xinjiang, other poor hinterland areas such as Tibet have also been targeted by this initiative to varying degrees since it was first rolled out in 1997.

Back then, officials were sent from developed regions to work and hold tenure in much poorer places. In what came to be known as the first round of the “pairing assistance for Xinjiang”, from 1997 to 2010, the ministries and local governments of 14 economically advanced provinces and municipalities reportedly invested nearly 30 billion yuan in Xinjiang’s infrastructure, and state media proclaimed that those authorities helped train more than 400,000 Xinjiang officials and civil servants at various levels.

In total, 19 of the country’s wealthiest cities and provinces are said to have boosted their assistance to the restive region and dozens of others via subsidies over the past 11 years.

Success, struggles and criticism

In Xinjiang, for instance, billions of yuans’ worth of ambitious infrastructure efforts, directed at raising the GDP in places such as Kashgar to the national level, resulted in what have, in recent years, been dubbed “ghost cities”.

Authorities begged businesspeople to come and establish businesses that were later abandoned. Some academics and pundits said the projects were not what the local population needed, while others said the region was not stable enough.

From 2014-19, the central budget’s annual transfer payments to Xinjiang expanded from 263.69 billion to 422.48 billion yuan.

And in the same period, state-run and government-backed enterprises from those 19 wealthy cities and provinces invested more than 2.3 trillion yuan in Xinjiang – from infrastructure projects to the property market to industrial estates, according to party mouthpiece People’s Daily.

Other official reports indicated that medical and educational talent was shifted to Xinjiang from developed inland areas.

But in July, the US said in its Xinjiang Supply Chain Business Advisory report that billions of yuan worth of pairing-assistance funding had been used to build factories in Xinjiang.

And some of these, the report alleged, directly involve the use of internment camp labour, while others mask abusive labour programmes that require parents to leave children as young as 18 months old in state-run orphanages and other facilities while they are forced or coerced to work full-time under constant surveillance. The children are later sent to state-run education and training facilities, the report claimed.

The Chinese government has consistently refuted all of these allegations, insisting that the “pairing assistance” programme helps Xinjiang people, especially members of ethnic minority groups, in lifting them out of poverty.

The general public in China is also told that these targeted aid programmes have a long history of providing economic means to address developmental imbalances, while simultaneously introducing cultural habits and attitudes from coastal areas, along with governmental concepts that align with the Communist Party’s directives.

And over the past decade, news reports have stated that Xinjiang’s migrant workers have chosen to work in factories across coastal provinces and cities. But local residents and small to medium-sized enterprises have also been quoted as saying they were given little access to Xinjiang workers.

In 2019, the Guangdong provincial human resources and social security department said a one-off subsidy of 4,000 yuan (US$620) per person was available to local enterprises and industrial estates that recruited and signed at least 30 labour contracts with workers from Xinjiang.

Conditions of their employment included subjecting them to ideological and political reviews, and their cultural assimilation was said to include being trained in the common language, laws and lifestyles. Meanwhile, factories in Guangdong were required to set up independent halal dining halls and dormitories for Xinjiang workers.

By the numbers

However, there has been a lack of official and third-party data offering more information on the Xinjiang workers who have migrated to factories across China.

In July 2020, foreign ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian was quoted by state media as saying that, among the 151,000 labourers from poor families in southern Xinjiang who had been transferred since 2018, 114,700 were in coastal provinces.

He also said transferred workers mainly worked in the manufacturing industries, such as those producing garments, footwear and electronics, and that they had an annual per capita income of more than 45,000 yuan (US$7,000).

The pairing-assistance programme has also helped Chinese companies open factories and industrial clusters in Xinjiang in some labour-intensive sectors, including the garment industry.

For example, the Guangdong Textile and Garment Industrial Park, located in Tumshuq city in west Xinjiang, is one of the largest pairing-assistance projects.

With investment from Dongguan Industrial Investment Holding Group and Dongguan-based fashion giant Yishion, the yarn-making operation was completed in 2020, with total investment hitting 3.94 billion yuan (US$611 million), state media outlet Economic Daily reported.

Its sales revenue reached 1.75 billion yuan in 2020 and was expected to top 2.5 billion yuan this year. The company currently has 4,168 employees, with more than 70 per cent belonging to ethnic minority groups.

Another example includes a sock producer from Jiangsu province that established a plant in Tumshuq city in May 2020 and laid out a three-year plan to invest 1.5 billion yuan, make 1.3 billion socks, and hire 10,000 local workers.

On the whole, however, the pairing-assistance programme seems to have achieved little success in boosting Xinjiang’s economy, according to official figures.

The wealth gap between Xinjiang and the rest of the country has only widened, with its per capita GDP expanding much more slowly than the nation as a whole. In 2015, it was 39,959 yuan – or about 81 per cent of China’s per capita GDP of 49,351 yuan that year. By 2019, Xinjiang’s per capita GDP increased to 54,280 yuan – or just 76 per cent of the national per capita GDP.

And last year, Xinjiang’s per capita GDP dipped to 53,593 yuan – 74 per cent of China’s average.

Nonetheless, Beijing said it had lifted all 3 million members of Xinjiang’s poor rural population out of poverty by the end of last year, and authorities said the pairing-assistance programme played an important role. Looking forward, Beijing says medical staff, teachers and government cadres will continue to be sent to Xinjiang each year.