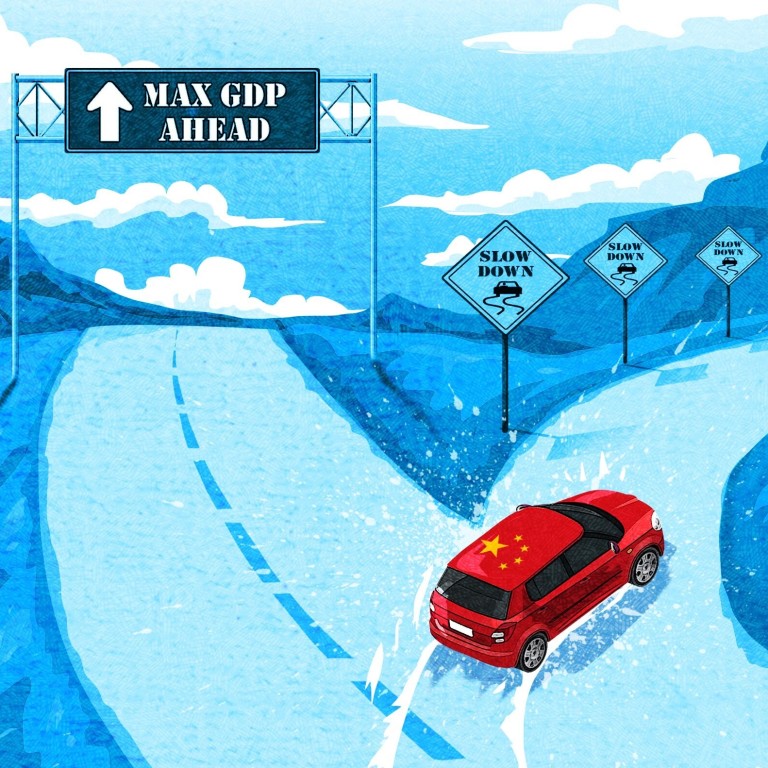

China’s economy downshifts to slower growth path as focus turns to social equality, national safety

- Beijing still wants to double China’s GDP by 2035, but ‘policymakers feel they need to address social issues to ensure social fairness and justice’

- Policy change prompts concerns that China is returning to a more nationalised economy that favours stability and protecting state enterprises

This is the first part in a series of stories looking at China’s economic outlook in the second half of 2021 as it continues its recovery from a coronavirus-hit 2020.

As US-China relations continue to deteriorate, Beijing is making a major policy shift towards social and economic governance that looks to be setting up a long-term decline in the nation’s corporate productivity and economic growth, according to analysts.

For starters, a number of restrictive factors – including demographic constraints on consumption, climate constraints on manufacturing, and macro constraints on monetary and fiscal policy – suggest China is facing a downshift to a slower growth path, said Richard Yetsenga, chief economist at ANZ Bank.

Why China cracked down on education, upending a US$70 billion industry

After China’s sharp economic recovery in the year’s first half, some economists now expect second-half economic growth to drop to about 5 to 6 per cent, year on year. And analysts say that could also be the full-year growth rate for 2022 – roughly the same growth path the country was on at the end of 2019, pre-coronavirus.

“China’s policy U-turn is tectonic,” Yetsenga said. “If tech is unable to sustain China’s high rate of growth, the focus will shift back to manufacturing and consumption. But both are facing structural challenges of their own.”

President Xi Jinping seemed to reinforce that in October when he said: “Common prosperity is a basic goal of Marxism and has long been a basic ideal of the Chinese people.”

“According to Marx and Engels’ vision, a communist society will completely eliminate the antagonisms and differences between classes, allocating resources according to one’s abilities and needs, so as to truly realise each individual’s freedom and complete development,” Xi said.

“The regulation change regarding education companies is rooted in an attempt to reduce the cost and burden of raising children, and so as to support fertility rates,” said Louis Kuijs, head of Asia economics at Oxford Economics. “I would not say it will help much on productivity growth. It won’t help much with rebalancing [the economy] away from [excess] investment.”

Kuijs expects that China’s economic growth will continue to slow to around 4 per cent by 2030, after the current volatile path of economic growth following the coronavirus crisis.

China has previously said its economic model needs to transition from one based on high levels of investment to one based on productivity growth, to help it catch up to leading global economies, and Beijing has set a goal of raising the nation’s average per capita income to US$20,000 by 2035.

This would mean that the path laid out for economic development would require a growth rate of at least 4.5 per cent each year for the next 20 years, said Chris Leung, an economist at DBS Group.

“The Chinese government now is very sensitive on foreign participation in all its industries,” Leung said. “They are afraid of importing Western ideologies that influence the thinking of China’s youth.”

This full year’s expected high economic growth rate of 8 to 9 per cent reflects last year’s low growth and is unlikely to be sustainable, said Chris Kushlis, a fixed-income sovereign analyst for Asian markets at T. Rowe Price.

Growth appears on track to slow to 5 to 5.5 per cent over the second half of the year. But there are a number of uncertainties around this outlook, Kushlis said, particularly pointing to the strength of export demand being more robust than expected this year, though this may fade as stimulus measures in other countries ease back and as reopening efforts potentially shift demand from goods to domestic services.

Moreover, efforts to control the real estate sector, along with the deleveraging agenda to curb the off-balance-sheet risks of local government borrowing, remain a high priority for policymakers, suggesting that there are will be continued downward pressure on local government spending that could slow activity. International experience strongly suggests that even orderly deleveraging is associated with lower growth rates, Kushlis said.

Kushlis also said China’s slowdown was inevitable because of structural factors, noting that “it becomes harder to continue to generate high rates of return on investment as it catches up with developed nations”.

“Reforms in the financial system are likely to be associated with some sacrifice to growth before longer-term benefits can be realised,” he said.

Capital Economics chief economist Mark Williams predicts 8 per cent growth this year, followed by 5.7 per cent in 2022, then a decline to around 2 per cent by the end of this decade.

The Politburo also warned that the pace of economic recovery would likely moderate in the second half of the year, mirroring the forecasts of analysts and economists.

[Beijing] is concerned with maintaining control over key parts of the economy. To that end, the state sector will remain protected

Williams speculated that productivity growth may no longer be one of Beijing’s primary objectives. “Instead, the leadership is concerned with maintaining control over key parts of the economy,” he said. “To that end, the state sector will remain protected.”

But state companies are not known for their effective operational management, prudent resource allocation or market-based decision-making, despite several rounds of rather tepid reforms aimed at addressing these deficiencies, Marro said, adding that this inherently carries risks of dampening optimisation and productivity.

“As national security concerns increasingly overshadow much-needed economic-reform policies, the structural issues in the economy – such as around debt, employment or low productivity – risk worsening,” Marro said. “This localisation push is at risk of forcing companies to switch away from foreign suppliers simply because they’re foreign, and not because it makes commercial sense to do so.”

Marro expects China’s GDP growth to hover around 3 per cent by the end of this decade, suggesting this would be a respectable pace of expansion given the size of China’s economy, but does not imply that issues around economic stagnation and financial risks will have receded by then.

And that, he said, makes this a tricky decade for Chinese policymakers to navigate.