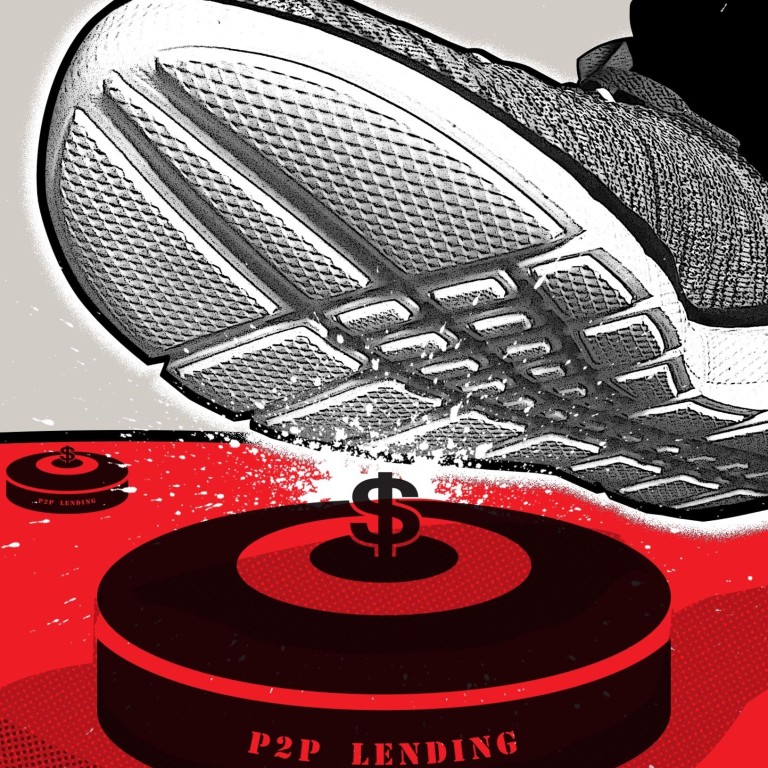

China’s P2P ‘financial refugees’ face never ending wait to recover lost US$120 billion

- Scores of Chinese investors suffered losses due to the collapse of peer-to-peer (P2P) lending schemes, with around 800 billion yuan (US$119 billion) still owed

- P2P firm Ezubao was one of the country’s biggest Ponzi schemes, fleecing more than 50 billion yuan from about 900,000 investors

An exporting company owner in his 40s in the eastern province of Zhejiang, a public relations manager in her 20s in the southern city of Shenzhen and retired state-owned enterprise executive in eastern-central coastal province of Jiangsu would normally share little in common as they blend into China’s 1.4 billion population.

In 2017, Liu Yijia from Zhejiang province, Li Wei from Shenzhen and Feng Mei from Jiangsu joined millions of people who put their savings into investment schemes that promised double digit annual returns – a big temptation compared to a one-year bank deposit rate of 1.75 per cent and a cash account interest rate of 0.3 per cent available at traditional banks.

Three years later, the three have been left frustrated as not only did they not receive the promised returns, but they also lost their principal investments.

Overall, it is estimated that millions, if not tens of millions, of Chinese citizens suffered losses due to the collapse of P2P lending schemes, with around 800 billion yuan (US$119 billion) still owed as the end of June, more than three and half years after the government crackdown on the sector began, according to Guo Shuqing, China’s top financial regulator.

At least eight people I know, including friends, colleagues and relatives, were victims of various P2P apps. We can’t get our money back. We called the police but there is no help

“At least eight people I know, including friends, colleagues and relatives, were victims of various P2P apps,” Li said. “We can’t get our money back. We called the police but there is no help.

“In the old days, everyone was talking about mass entrepreneurship and innovation. I felt that P2P was a very high-end and innovative thing to do and was something encouraged by the government. No one around me was not tempted [by the promised] yields … but now we don’t even want to talk about these schemes.

“In recent months, two of my friends also joined me as financial victims after [a funding scheme] failed to make a redemption. I have sworn to never again invest in financial products in China, either public or private.”

The actual number of P2P investors in China is unknown, but China’s financial industry watchdog estimated the total number fell by 88 per cent between early 2019 and late August this year.

01:47

China GDP: economy grew by 4.9 per cent in third quarter of 2020

A separate report by the National Committee of Experts on Internet Financial Security Technology, a monitoring agency established in 2016 by China’s industry ministry, said there were “at least 50 million” in late June 2018, with each person investing roughly 22,788 yuan (US$3,400).

Liu had been enticed by a brochure from the Hangzhou-based JC Group offering “wealth management products” that promised an annual return of 12 per cent. He invested the minimum amount of 1 million yuan (US$148,000), with JC Group stating that it had signed deals with many local governments to build “charming small towns”.

The company managed at least 350 “private funds” and raised around US$10 billion before its head office was raided by the police and its founder was arrested on a charge of illegal fundraising in April 2019.

“My clients, most of them high-net-worth individuals, are in a fierce mood. They are angry at the insufficiency of the judicial process for these cases,” said Zhong Jian, partner at DHH Law Firm, which represents dozens of investors in cases against several wealth management product providers.

They always thought of themselves as the winners or beneficiaries of China’s reform and opening up, but after the bubble burst they found they had no way to defend their rights.

“They always thought of themselves as the winners or beneficiaries of China’s reform and opening up, but after the bubble burst, they found they had no way to defend their rights. Since the filing of the lawsuits last year, there’s been little progress.

“High-net-worth individuals were originally fully confident in the system and supported the system, but now they have doubts. If they lose confidence in the domestic investment environment, their wealth will definitely flow abroad.”

Feng from Jiangsu was also convinced by the high returns on offer by JC Group, and invested 2.6 million yuan (US$388,000).

Li from Shenzhen, who was in comparison relatively poorer than Liu and Feng as he was living only on his monthly wages, took the risk to invest his entire life savings of around 200,000 yuan (US$30,000) through an app on her mobile phone.

The Chinese public are naive. We have never had this type of freedom, Bravo! Go for it

They offered an easy alternative to banks, often only requiring a few swipes on a mobile phone to transfer money from a bank saving account.

But in the absence of government supervision, fraud was rampant, with many identified as Ponzi schemes which used new money to pay off existing financial obligations.

Joe Zhang, a veteran Chinese financial industry watcher who is now the chairman of Slow Bull Capital, said China’s financial depression, namely banks offering lower interest rates to savers, and the lack of regulatory oversight made the country a fertile ground for P2P schemes to flourish.

“The Chinese public are naive. We have never had this type of freedom, Bravo! Go for it,” Zhang said, referring to the public mood. “P2P firms have no leverage ratios to speak of. So effectively their leverage ratio was infinity … finally, many borrowers think they may not have to repay the debts.”

How big is China's debt, who owns it and what is next?

One of these schemes, the Shanghai-based Tangxiaoseng, raised 59 billion yuan (US$8.8 billion) from 2.77 million investors between 2012 and 2018. It collapsed owing 5 billion yuan to 110,000 investors, with ring leader Wang Li sentenced to life in prison, and three other executives given jail terms of up to 14 years.

Often investors suddenly found they were unable to withdraw money from a scheme, which in Chinese is called Bao Lei, literally meaning a landmine has exploded.

This has left hordes of financial refugees, who feel helpless and abandoned by China’s legal system that offers no remedy for them to recover their money back.

For those lucky enough to get some of their money back, the process can be long and the losses severe. In one of the biggest fraud cases involving Ezubao, the recovery rate for investors was around 35 per cent of their original investment.

Shadow banking back in vogue in China as assets grow for the first time since 2017

In addition, the potential loss of 800 billion yuan represents only a tiny portion of China’s family wealth. In September alone, 9.95 trillion yuan was deposited in banks by Chinese households, meaning Beijing’s clamp down on P2P schemes has created little impact on general financial stability.

In the process of dealing with financial risks, financial institutions and their shareholders should bear the main responsibility to the financial risks

Investors like Liu and Feng are still pursuing their legal cases against JC Group along with around 3,000 others, but China’s judicial and economic investigation resources are seen as insufficient to properly investigate all the cases.

“Negotiated settlements may be more effective in many of such cases,” said Zhao Xijun, associate dean of Renmin University’s School of Finance.

Central bank governor Yi Gang said earlier this month that the shareholders of the financial institutions involved should assume the financial losses and that insolvent institutions should exit the market according to law.

“In the process of dealing with financial risks, financial institutions and their shareholders should bear the main responsibility to the financial risks, and the local governments shall be responsible for implementing supervision and administration and strengthening liability for territorial risk disposition,” Yi wrote in an article published by China Finance magazine earlier this month.