China’s private firms in traditional low-tech sectors struggling without government support

- Lack of access to capital at an affordable rate remains primary problem facing small and medium-sized manufacturers

- Hi-tech firms get support from national and local governments, but traditional low-end manufacturers do not

Among China’s millions of private businesses, Terry Wu says his is one of a minority of non-state firms that have benefited from government incentives to support the private sector, which Beijing is counting on as an important lifeline to buffer the nation’s overall economic slowdown.

Wu’s company, a manufacturer of smart devices and components including camera modules for smartphones, has enjoyed five years of free factory rental and easy access to bank loans as part of a sweeping policy initiative by local authorities in Jiangsu, one of China’s most prosperous provinces.

“[Government policies] have supported us in areas like automation, hi-tech products, research and development,” said Wu, a vice-president of the firm.

The Chinese leadership has listed “high quality development of the manufacturing” as a priority in economic works. At the gathering of China’s 25-member Politburo, the supreme ruling body, on Friday, they agreed that China will keep “upgrading traditional industries and making emerging industries bigger”.

“We must effective support the development of private businesses and small firms”, according to the statement of the meeting published by the official Xinhua news agency. “We will guide private businesses with clear advantages to transform and to upgrade.”

Wu said the government support was available for him because his company – which he declined to name – belonged to the hi-tech industry that the country was pushing to lift its manufacturing value chain as it struggles to reform its economic structure to reach the next stage of economic development – all while China engages in a prolonged trade war with the US.

Many more of China’s estimated 27 million private firms – with roots in the traditional low-end manufacturing that has propelled the economy’s rise to become the world’s second largest – are struggling or have already become casualties of Beijing’s two-year crackdown on risky lending and informal loan channels on which they previously depended, compounded by the economic slump.

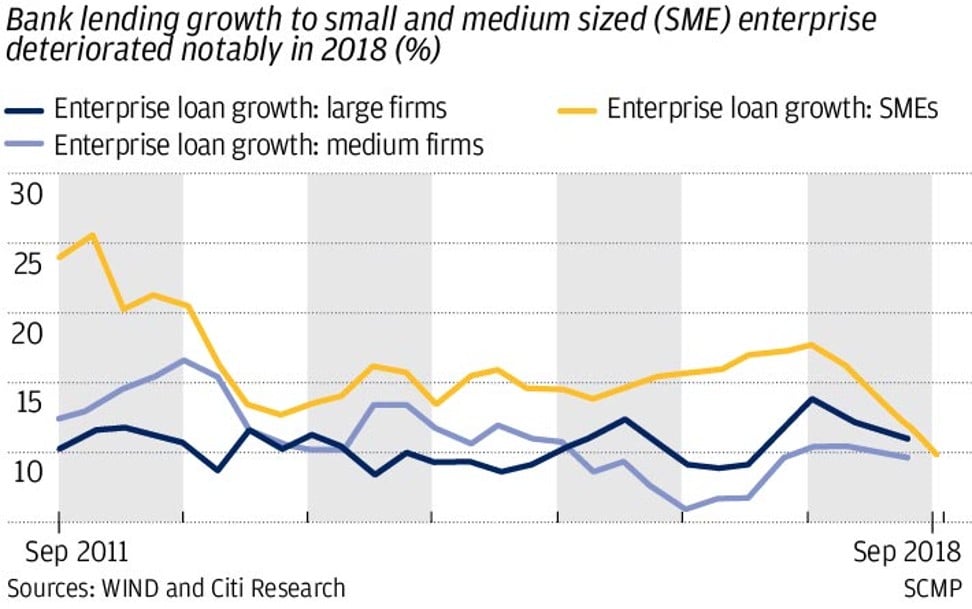

Since late 2018, Beijing has introduced a series of policies to support the private sector’s development, including tax cuts and repeated calls to banks to lend more to these firms.

The government is aiming to deliver 2 trillion yuan (US$298 billion) in tax cuts this year to help companies and encourage individuals to spend more to bolster consumption. The value-added tax rate for manufacturers will drop from 16 to 13 per cent, while the rate for the transport and construction sectors will drop from 10 to 9 per cent. Tax authorities said they cut 143.7 billion yuan (US$21.4 billion) worth of concessionary taxes and fees for micro and small enterprises in the first three quarters of 2018, an increase of 41.3 per cent from same period the previous year, according to a report in the Communist Party mouthpiece People’s Daily.

But many private entrepreneurs are unimpressed, arguing that their woes begin before the start of the manufacturing process – meaning, when trying to raise capital – and not at the end when taxes are paid. And development of manufacturing at small and medium-sized firms (SMEs) has been obstructed by three major factors, they say: lack of access to adequate capital at an affordable price; a shrinking marketplace because of slumping exports and domestic growth; and the challenge of upgrading machinery and worker skills to move up the manufacturing value chain.

To be sure, Chinese banks traditionally prefer to lend to state-owned enterprises because of the implicit backing from the government should a business fail. When they do lend to SMEs, they stringently screen the firm’s executives’ personal credit ratings.

We must effective support the development of private businesses and small firms. We will guide private businesses with clear advantages to transform and to upgrade.

Because comprehensive ratings materials are not readily available, so-called credit agencies have sprouted up that focus on collecting data and documents for banks’ verification needs, said a senior executive from a money lending company who previously worked at a couple of the big four state-owned banks. To meet a bank’s lending criteria, these agencies had no qualms about helping firms cook their books to secure a loan, the executive said.

Shadow bankers were just as discerning as loan officers at the big banks, said the money lender executive who agreed to speak on condition of anonymity. Lending to private businesses, often without a government’s implicit backing or tangible assets like property, is considered a risky undertaking.

Amid the tougher economic and business climate, informal lenders were also upping their game by specialising in particular industries, the source said.

For example, lenders that focus on steel and construction businesses related to infrastructure projects will have in-house know-how to evaluate and control risks lending to such projects. Interest rates for infrastructure projects are usually higher than those charged by banks but lower than loans for other industries because they are considered stable, low-risk investments.

In contrast, lending costs for traditional manufacturers in electronic accessories and clothing could be as much as 20 to 30 per cent because their industries can undergo rapid changes with little warning, with multiple variables like exchange rates and sales prices affecting profit levels.

The executive said it helped if companies pledged property as collateral or a third party guaranteed a loan, as informal lenders were “Shylocks” who were more interested in the borrowers’ properties than the interest payments on the loan.

“Factory equipment or pairs of jeans aren’t hard currency, so they are not used as reliable collateral,” he said. “The real intent of [informal] lending now is to take over your house, your factory building.”

Private firms may contribute up to 60 per cent of China’s growth and 80 per cent of urban employment, but they have taken the brunt of the economic downturn.

Some have been forced to sell out to state-owned firms, which increasingly account for growth in industrial production and profits. Wind Information estimated that in the first nine months of last year more than 20 listed private firms were sold to SOEs.

Wu said he expected the business climate to remain difficult for private firms this year, with survival dependent on three broad practices: cutting costs, developing indigenous products with intellectual property and leveraging government policies for steady funding.

“But it’s very difficult to achieve all three,” he said.