Black Panther soundtrack carries on tradition of black movie music that stretches back decades

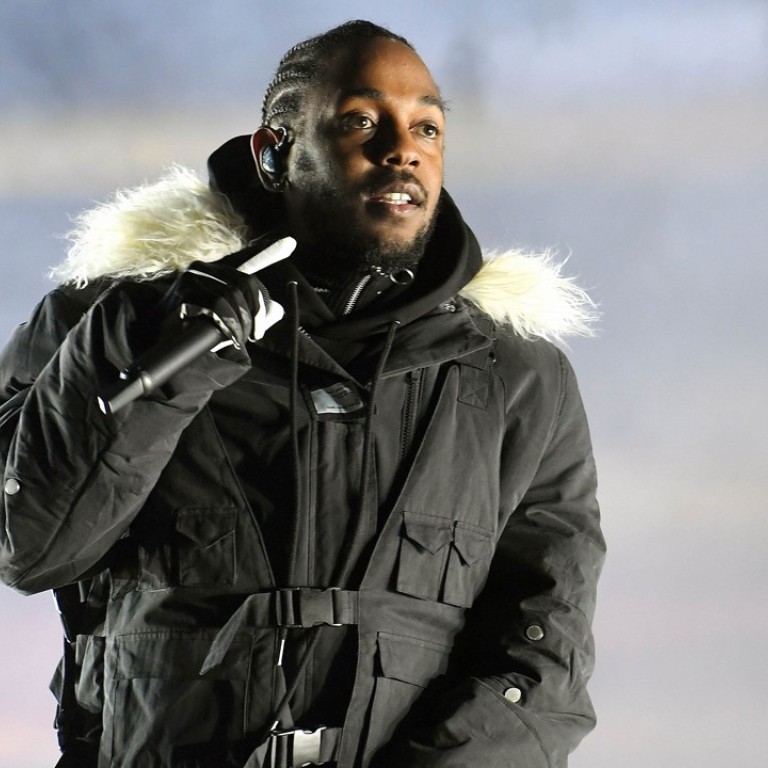

Kendrick Lamar put together the superhero film’s soundtrack, and it is every bit as good as predecessors from Boyz n the Hood and Waiting to Exhale in the 1990s to Purple Rain and Do the Right Thing in the 1980s

“It’s not a funeral,” the bad guy sneers, and suddenly we’re being pummelled by Opps, a throbbing, darkly futuristic hip-hop tune by a trio of rappers led by Kendrick Lamar, who put together the movie’s all-star soundtrack and appears on each of its 14 songs.

With Black Panther out, we rank Marvel Cinematic Universe films from the worst – Thor 2 – to the best

The villain’s line is a bleak joke, of course, but he is dead-on about his surroundings: Black Panther is most definitely not a funeral, and its wildly creative music accounts for much of its vital life force.

A superhero movie with a soul, director Ryan Coogler’s thrilling and heartfelt picture radiates positive energy as it follows T’Challa, king of the fictional African nation of Wakanda, in his struggle to protect his prosperous homeland while simultaneously empowering marginalised people around the world with the use of the Wakandans’ advanced technology.

What’s more, the film – featuring a mostly black cast that includes Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong’o and Angela Bassett – is being viewed by many with hopes that it will begin a new era of African American representation in Hollywood cinema.

“This may be the night that my dreams might let me know / All the stars are closer,” SZA sings in All the Stars, a yearning duet with Lamar, and the lyric could be the inner monologue of a young woman watching Black Panther and finally recognising an image of herself on screen.

For all the ways in which it looks forward, though, Black Panther also proudly adheres to an established tradition of black movie music that stretches back decades – through Boyz n the Hood and Waiting to Exhale in the 1990s to Purple Rain and Do the Right Thing in the 1980s to Super Fly and Shaft in the 1970s.

The idea, in contrast with many of today’s more obligatory soundtracks, is not merely to assemble a collection of songs to wallpaper a blockbuster or to extend its pop-culture footprint to top 40 radio (or to Spotify).

Rather, what connects these films and their accompanying albums to each other is the shared determination to utilise music as a storytelling device – including tunes delivered from characters’ points of view – and to reflect the sprawl of an ambitious narrative with a soundtrack that coheres even as it showcases a diversity of styles.

Lamar plugs into a feel-good vibe on Black Panther: The Album without flinching from the tough questions the movie asks about race and identity and the burden of leadership. With luck, the result will propel other musicians and filmmakers toward similar ambitions. Often hailed as the most important rapper of his generation, the 30-year-old was an inspired choice to handle the project, for which he is credited as executive producer alongside the head of his record label, Anthony Tiffith, known as Top Dawg.

Like Curtis Mayfield or Prince or Kenny “Babyface” Edmonds, to name three earlier soundtrack auteurs, Lamar understands how to package sophisticated concepts to make “entertainment that has artistic integrity”, as Coogler described it recently.

Black Panther has fifth highest debut ever at North American cinemas, and it’s a blockbuster in the true sense of the word

The director said he was drawn to the “introspective” quality of Lamar’s work, including last year’s Grammy-winning Damn album, with its thoughts on the personal costs of black achievement in Donald Trump’s America.

Yet Lamar spins a great yarn – so much so, Coogler pointed out, that he subtitled his 2012 breakthrough, “good kid, m.A.A.d city,” a “short film by Kendrick Lamar”. “You always feel like you’re going on a cinematic journey with him,” the director said.

On Black Panther, that journey is in part a physical one. With contributions from a deep bench of international talent, the album roves from Lamar’s native Southern California (also represented by Vince Staples, Anderson .Paak and various members of Lamar’s TDE crew) to Atlanta (2 Chainz, Future) and England (James Blake, Jorja Smith) and South Africa, where some of the soundtrack’s most gripping voices come from, including the singer Sjava and rapper Yugen Blakrok.

Guided by Lamar and his long-time studio partner Sounwave, along with a bevy of additional songwriters and producers, these artists together weave a dense and often gorgeous fabric of sound.

You always feel like you’re going on a cinematic journey with him

There are shimmering electro-R&B jams such as Khalid and Swae Lee’s The Ways and Redemption, by the duo of Zacari and Babes Wodumo, a South African club star who imports the dance groove called gqom. There are slow-motion ballads like Smith’s bluesy I Am. And there are rowdy hip-hop cuts like King’s Dead, which has Lamar trading verses with Jay Rock and Future and features a trippy interlude sung by James Blake.

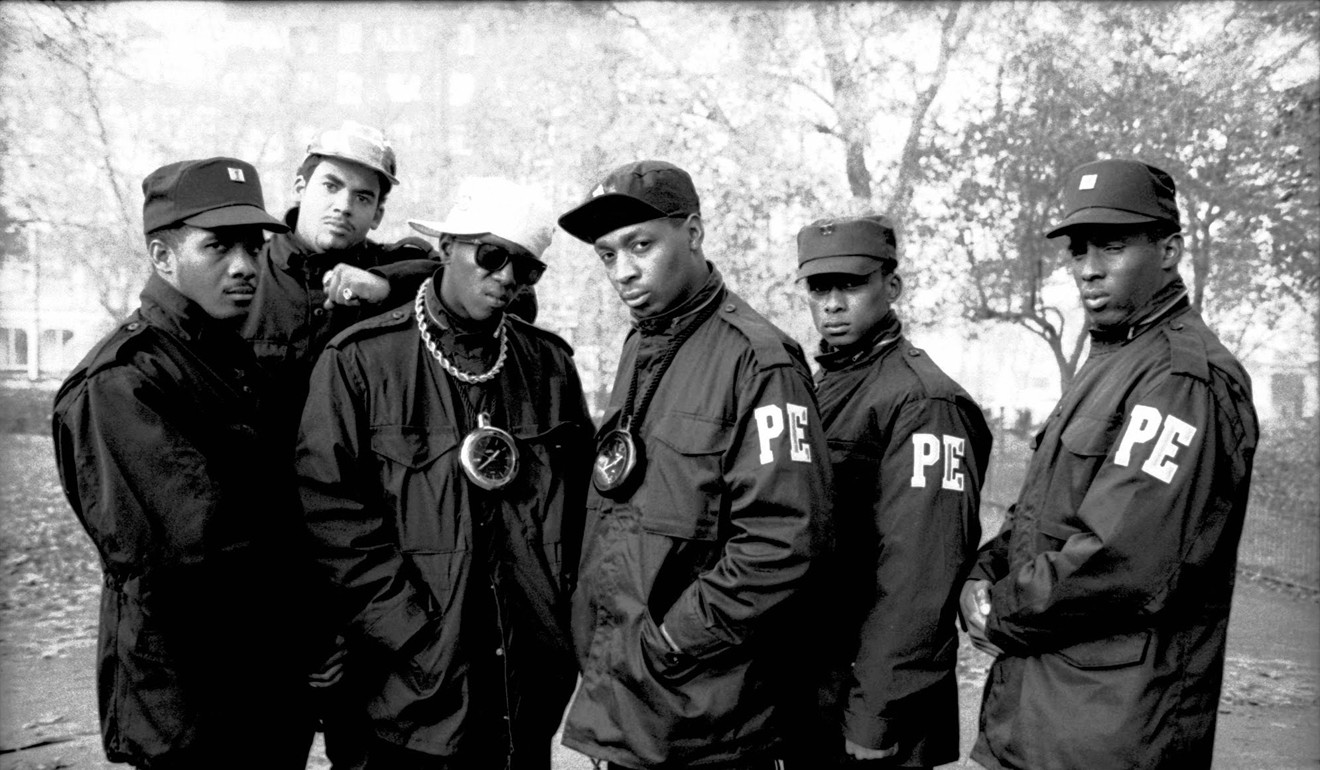

Opps is another of those, with fierce rhymes from Lamar, Staples and Blakrok over a noisy beat that imagines a SoundCloud-era update of the Bomb Squad’s groundbreaking production for Public Enemy. (In Black Panther’s prologue, set in 1992, we see a Public Enemy poster hanging on a character’s wall – a nifty acknowledgement of the group whose Fight the Power still conjures visions of Spike Lee’s powder-keg Brooklyn.)

Like the movie, which ponders the value of open borders, the Black Panther album uses this variety to embody and examine ideas about the African diaspora at a time of increasing immigration control. In that it shares some DNA with Drake’s globe-tripping 2017 effort, More Life, which came out just weeks before Damn”

But where the famously self-absorbed Drake rarely deviates from his own point of view, Lamar on Black Panther frequently adopts the voices of T’Challa and the king’s rival, Erik Killmonger.

“I dropped a million tears / I know several responsibilities put me here,” he raps in the opening title track, before demanding, “What do you stand for? Are you an activist? What are your city plans for?”

That Lamar himself is acquainted with these questions only makes his portrayal more convincing, as was the case when Ice Cube did How to Survive in South Central in Boyz n the Hood.

“In LA heroes don’t fly through the sky of stars / They live behind bars,” Ice Cube rapped in that song, merging his perspective with that of his indelible character, Doughboy.

Marvel’s superhero Black Panther invades New York Fashion Week

Nearly 30 years later, Lamar and Black Panther show how much has changed since then – and how much hasn’t.