Myanmar music festivals help to unite youth, heal old wounds and work for a better future

Global non-profit group Turning Tables has staged concerts in troubled countries like Tunisia, Lebanon, and Libya to help young people express themselves creatively. Now Asia is also starting to reap the benefits

However, wherever freedom of expression is threatened or an uprising is underway, that is where Turning Tables goes.

Turning Tables is a global non-profit group that establishes music and film production studios, and stages concerts in areas where young people lack the means to express themselves creatively.

Black Eyed Peas enter new era of hip hop – forget party bangers, it’s all about music with a purpose

One of its co-founders is Martin Jakobsen, originally from Copenhagen, Denmark. Turning Tables was born in 2009, when Jakobsen, now 38, was living in Beirut. He was playing in a DJ collective at the time, flying back and forth between Europe and the Middle East to tour.

The collective gigged heavily in Scandinavia, but when Jakobsen attempted to bring the group to Lebanon and approached the cultural arm of the Danish government for financial support, the response was less than encouraging.

“They said, ‘Hell no’,” Jakobsen says in an interview in Yangon, Myanmar, last December during the Voice of the Youth music festival, the latest initiative of Turning Tables.

“We had to do something else,” he says. “They wouldn’t just give us money to go and play. So we said, ‘Let’s do some shows in the Palestinian refugee camps’. So we launched Turning Tables and went and did some studio workshops. We saw how the kids reacted when you put a microphone in their hands. They were desperate for a way to express what it feels like to be at the bottom of the food chain.”

The following year, the revolts of the Arab Spring began throughout the Middle East and North Africa, starting in Tunisia, later spreading to Libya, Egypt, Yemen, Syria and Bahrain. Jakobsen and Turning Tables expanded their efforts in the region, putting on festivals in countries where conflicts were ongoing.

“Right after [Libyan leader Muammar] Gaddafi fell, because musical instruments had been banned, you saw an explosion of people doing metal, jazz, rap, whatever they could get their hands on,” says Jakobsen. “So that was like a bloom in a desert and it didn’t last long, unfortunately. But we managed to squeeze in a festival in Benghazi, and we did one in Tunisia as well.”

Now based out of Amman, Jordan, Jakobsen continues to take Turning Tables to more locations around the world. In 2015, the organisation staged the first in what has become an annual series of concerts called Voice of the Youth in Yangon. As has been the case wherever his group operates, Jakobsen has sought to empower locals to take the lead.

In Yangon, the head of the local office of Turning Tables is 36-year-old Swe Hlaing Htet, better known to many in Myanmar music scene circles as Darko C, guitarist, songwriter, and singer for Myanmese post-punk rockers Side Effect.

Darko is fighting a battle on two fronts. On one side, he works to show Myanmese people that after a past in which the music scene was rife with violence between fans and musicians of different styles, festivals such as Voice of the Youth, that welcome all types of music, can be held peacefully.

Rita Ora talks about her new album, getting back on the road and returning to Hong Kong

“Rock music has been seen by people as a place where fights happen,” Darko says. “In the past, it was kind of true. When I was a kid and I was going to these concerts, my parents were super worried.”

To that end, Voice of the Youth has been a success. The past three years, including the 2017 edition last December, were free of the clashes between punks and rappers that had plagued other mixed-genre festivals in Myanmar. The other battle Darko wages is cultural. He says that in his country, free speech is at best a distant memory for those who grew up under the military junta, which ended in 2010 after nearly 50 years in power. He added that the concept of freedom of expression is at odds with Myanmar’s culture of non-confrontation and deference to elders.

“There are many social taboos,” he says. “If you just say something wrong, you can never fix that relationship. There is so much fear when it comes to communication. That is one part that I want to change.”

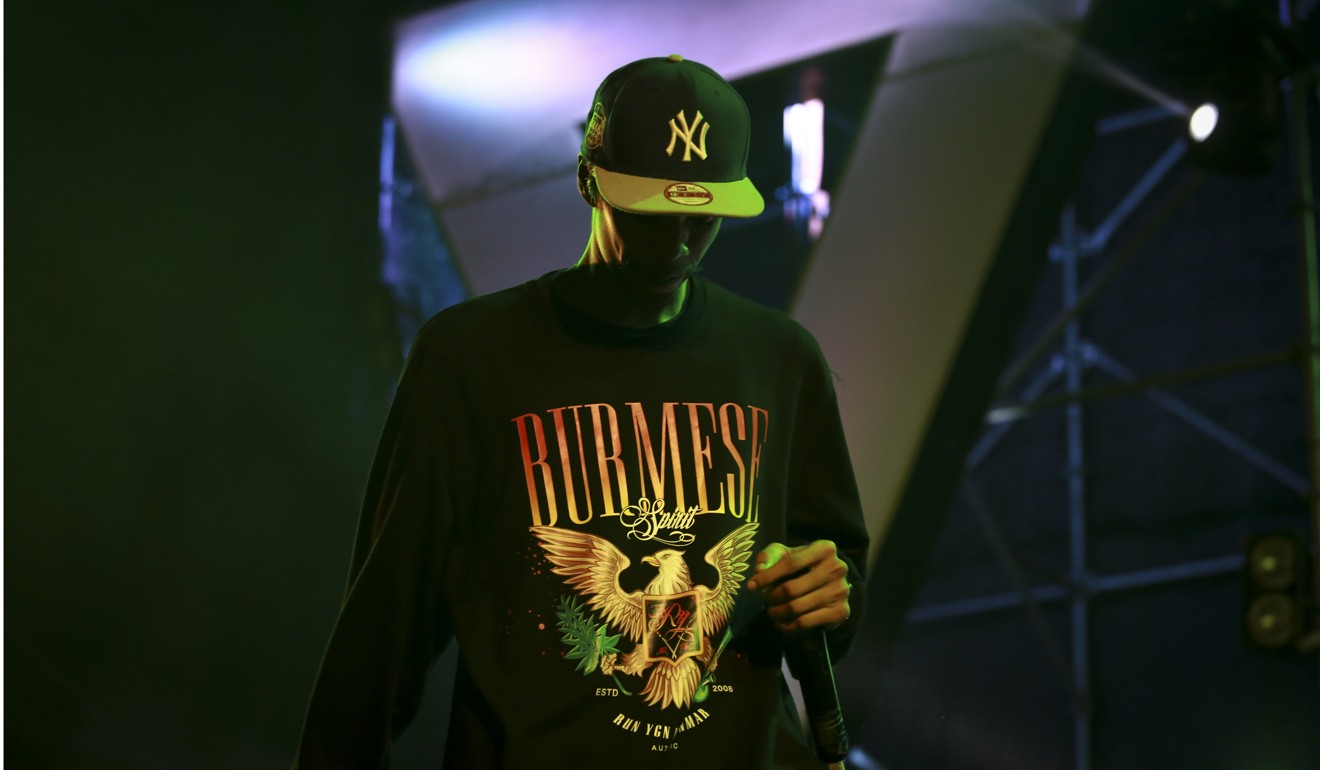

And so Darko leads by example. At Voice of the Youth in Yangon last December, at an outdoor stage by the shore of Kandawgyi Lake, he took time between songs to address issues facing Myanmese society. He alluded to the military campaign against the Muslim Rohingya people in Rakhine State that has forced the stateless minority to seek safety in refugee camps across the border in Bangladesh. Speaking to the thousands in attendance, Darko said it plainly: “What happened to those people was not right.”

Darko later admits that his country, which has more than 135 different ethnic groups and around 100 spoken languages, lacks unity. This, he says, is precisely why Myanmar must re-engage with the freedom of expression it knew in the past, before the days of military repression.

“Room to express yourself can reduce a lot of tension, because here the society, our culture, we are not very much outspoken. For example, you can’t say no to your parents. We grew up with that culture, and that is also embedded in the education system and also within the government administration system. Now we are trying to have a cultural revolution to give [people] the space to say whatever they want.

Speaking about sensitive topics does not present the danger it did during military rule, but this doesn’t mean it’s entirely safe, Darko admits. “There’s still a risk, of course. That is why we’re doing this very carefully,” he says.

Many Myanmese are not ready for an age in which all opinions, no matter how popular or unpopular they may be, have a platform. But in order for Turning Tables to achieve its ultimate aim – allowing people to say whatever they want, whenever they want – boundaries will inevitably have to be pushed.

BTS pave way for K-pop golden age in US, achieving what Psy and Wonder Girls failed to accomplish

“One woman told us that ‘freedom of expression is not about swearing. You can’t swear at the president’,” says Darko. “But I think we should be able to, actually. If you are a public figure, you have to deal with that. That is something we are still fighting for – to give the next generation a chance for freedom of expression.”