Like Brokeback Mountain but in Yorkshire: English farmer’s son on his film God’s Own Country

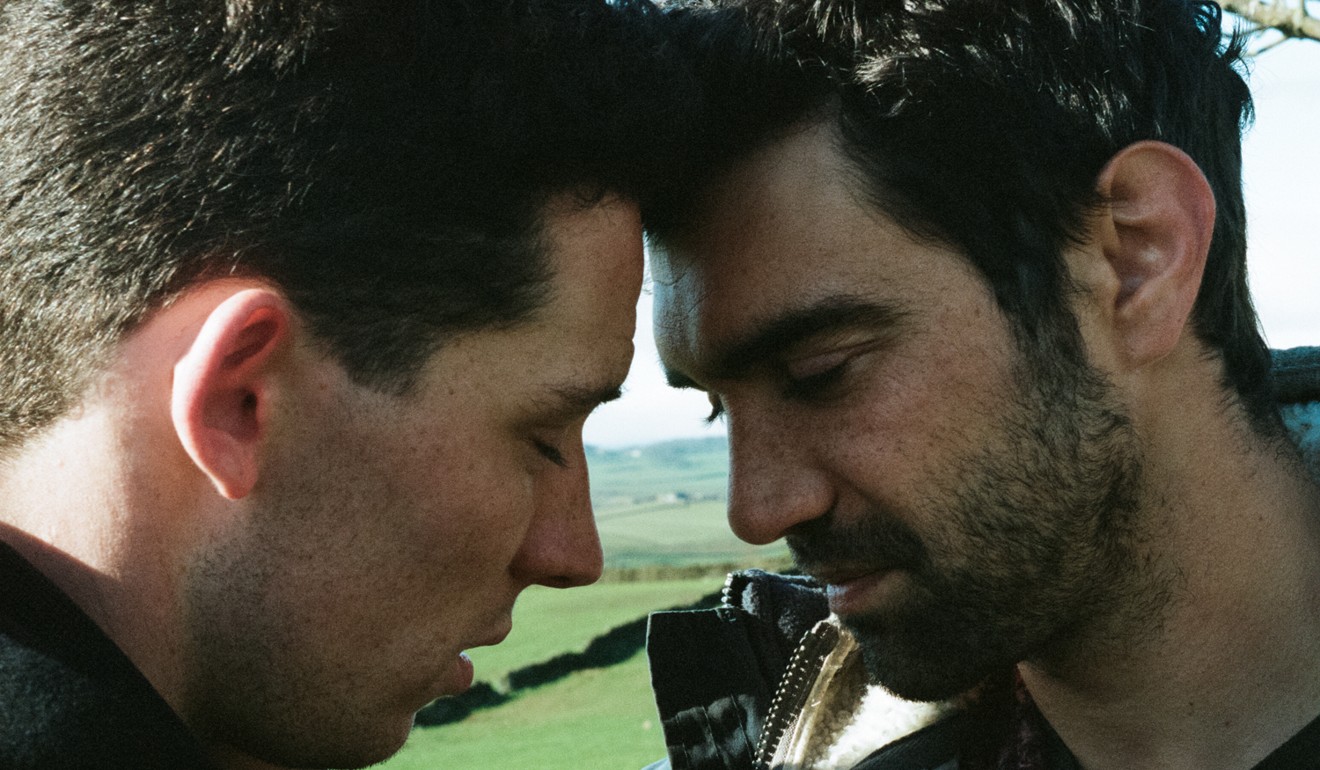

Director of the most acclaimed new British film in years, Francis Lee brought his own experience of life on a northern English farm to the story. Its star insists that, despite comparisons with Ang Lee’s film, it is not about sexual repression or coming out

Francis Lee’s God’s Own Country is one of the most acclaimed British debut films in years, and it is about as home-grown as it gets.

“I grew up on that hill where the film is set,” says the filmmaker. That “hill” is in Yorkshire’s Pennines, in the north of England, where his father was a sheep farmer. “I was obsessed with the landscape and the people and the world and I had never seen it depicted on screen in the way that I saw it.”

What to see at Hong Kong’s Sundance Film Festival 2018

While Lee left for London to study acting when he was 20, he couldn’t shake those hills from his mind. Years later, after a career on stage and screen and with a couple of short films under his belt, he returned with the idea for God’s Own Country.

“It is biographical of the farm and the land and the animals and the weather,” he says. “The actual characters are not. That’s not my family … I actually had quite a happy childhood.”

Indeed, it would be hard to imagine someone with an upbringing as troubled as the 24 year-old Johnny (Josh O’Connor), the film’s central character. With his father (Ian Hart) debilitated by a stroke and his grandmother (Gemma Jones) too elderly, the responsibility falls on him to tend the family farm. Binge-drinking as a consequence, he’s also contending with his repressed sexuality, feelings that spill out when he meets Romanian farm hand Gheorghe (Alec Secareanu).

Already, the film has drawn comparisons to 2005’s Brokeback Mountain, Ang Lee’s groundbreaking love story between a cowboy and a rodeo star which ushered in a new era of gay cinema into the mainstream. Before that, such tales were largely confined to the independent sector, part of the so-called New Queer Cinema wave of films spearheaded by Todd Haynes’ Poison and Rose Troche’s Go Fish in the early 1990s.

Lee’s film premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2017, alongside Luca Guadagnino’s Call Me by Your Name , another tale of male love and sexual experience (which went on to win an Oscar for best screenplay). While the two films couldn’t be more different – Guadagnino’s world is lush and languid, Lee’s is as harsh as calloused hands – neither presents homosexuality as troubled, angst-ridden, or beset by violence or prejudice.

“I always knew that I didn’t want to write a film that was issue-based around sexuality,” says Lee. “I wanted to make a film that was first and foremost a love story and about how hard it is to fall in love, and to make yourself vulnerable, and to make yourself open to love and to be loved. In my experience, I hadn’t seen issues around sexuality in my family or in the local community, so I kind of knew that I could depict that in a truthful way.”

If anything this suggests a huge leap since even Brokeback Mountain, where the male characters played by Jake Gyllenhaal and Heath Ledger were married and their assignations were seen as shameful.

“I think it’s one of the things that I really loved about the film,” adds O’Connor, the Cheltenham-born British actor whose middle-class upbringing is a world away from the inarticulate Johnny. “It’s not a film about repression and it’s not a coming out film … the issues in that family are about lack of communication.”

Venice film festival 2018: far right in focus, Westerns make comeback

Moreover, to borrow from the industry paper Variety review for Lee’s film, there are “pockets of tolerance in unexpected places”, not least his family.

“They see Johnny being very angry, sad and lonely and it affects his work,” says Lee. “They need him to be there to work otherwise, if he isn’t, they’ll lose the farm.” With Gheorghe on the scene, suddenly he’s no longer binge-drinking and is inspired to farm. “I don’t see why they wouldn’t support that.”

Previously acting with Mike Leigh in his 1999 Gilbert and Sullivan tale Topsy Turvy, Lee was keen to craft his characters with the same authenticity and attention to detail. He recalls taking O’Connor on set. “I’d say to Josh, ‘OK, this is Johnny’s bedroom. Where does he have his bed? Why does he have it there? What is the warmest part of the room? What would he have on his shelves? What’s under his bed? What’s in his drawers? What’s in his pockets?’”

In preparation, both O’Connor and Secareanu worked on separate farms to learn about the worlds of their characters. “Francis tried to keep us apart as much as he could, for the characters – and their story – to be as truthful and natural as it could,” says Secareanu.

The director initially suggested keeping them entirely separate until the shoot. “But that’s really hard, when you have to rehearse the love scenes, which are very technical,” says O’Connor. “It’s like choreographing a dance.”

Lee’s film – which was nominated for outstanding British feature at the Baftas this year – isn’t the only British film to try this lately. Hope Dickson Leach’s Somerset-based The Levelling and Clio Barnard’s Dark River – also Yorkshire-set – similarly show the economic challenges farmers are now under.

Hereditary: the story of Toni Collette indie horror hit

“It’s very tough,” says Lee, whose father now farms on the outskirts of Keighley, close to where they shot. “All I can tell you is that my dad is still working at 75 years old and, yeah, it’s a struggle.”

The film also points to the issue of immigration – a hot-button topic in the UK during the Brexit campaign. Lee worked with a Romanian when he got a job at a junkyard shortly after Romania joined the EU in 2007. “There was a lot of publicity in the UK at that time about Romanians coming to exploit the UK system. When I met him and I heard it from a very personal and emotional point of view, I was really ashamed of the UK.”

Despite blending in political and socio-economic issues into the backdrop, God’s Own Country never feels like a state-of-the-nation address. “I think the film’s more about people becoming vulnerable and accepting emotion, articulating emotion and opening themselves up for pain,” says O’Connor, who has since been cast as Prince Charles in season three of The Crown. “The fact that it’s two men is, in some ways, irrelevant.”

Now that sounds like progress.

God’s Own Country opens on September 27

Want more articles like this? Follow SCMP Film on Facebook

(1).JPG?itok=0BHk6odg&v=1665981271)