The real horrors behind Netflix’s The Haunting of Hill House

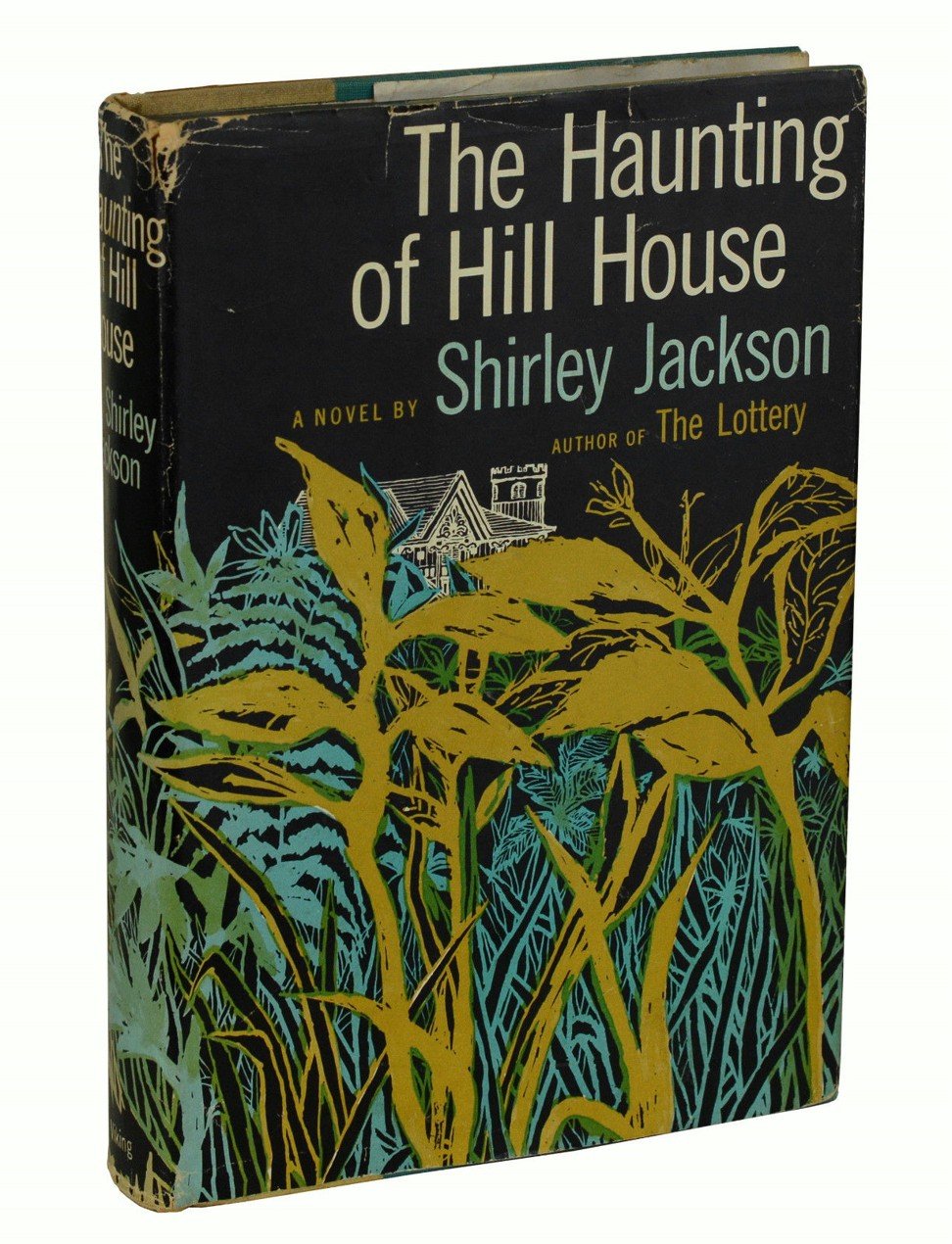

- Stephen King says Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House is ‘nearly perfect’

- Jackson’s 1959 book has been turned into a 10-part Netflix series

- The book evokes dark visions of duty and domesticity

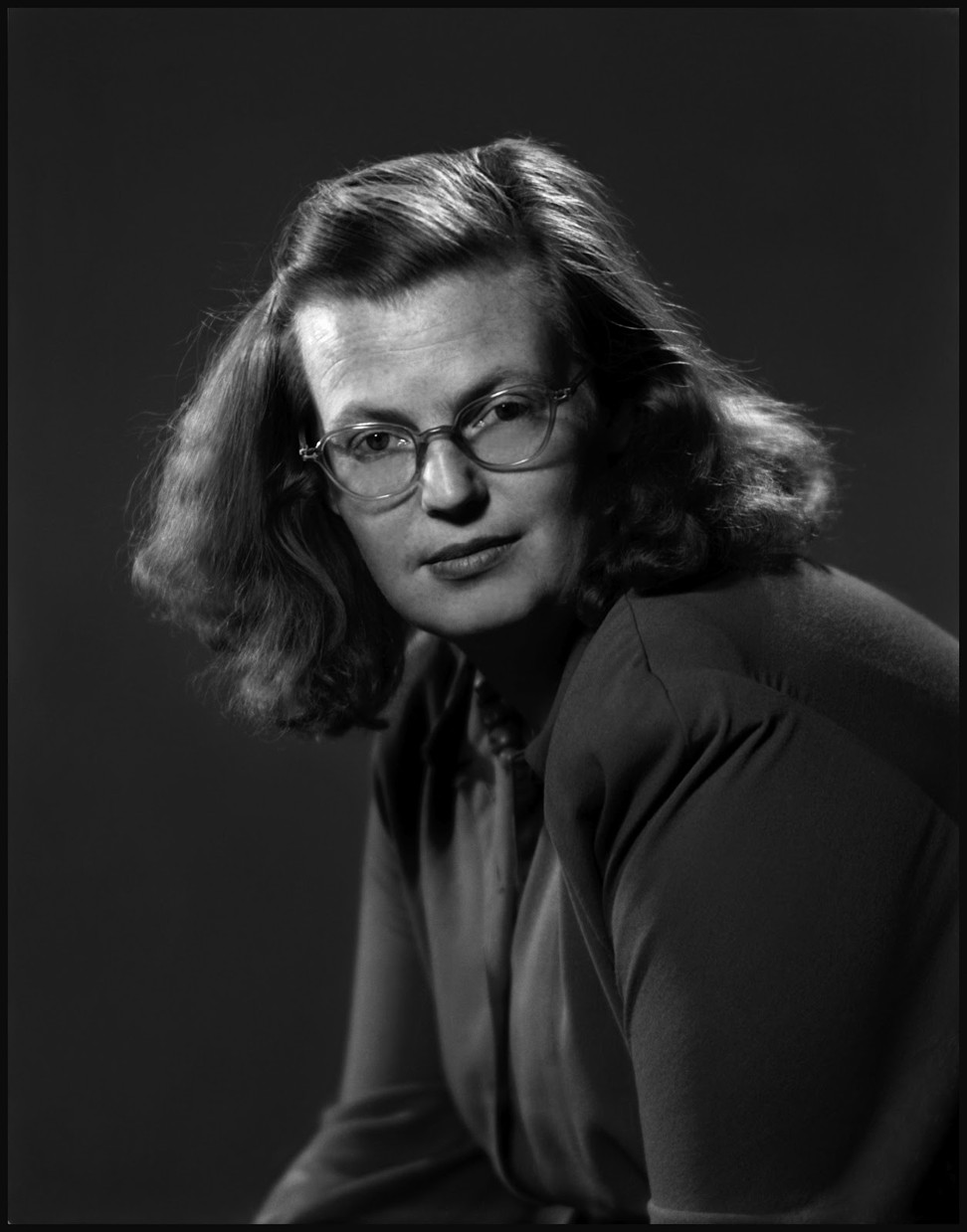

Anyone who has read Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House – now finding a new audience as a popular Netflix adaptation – will find a couple of details of its 1959 reception almost too neat to be true.

Jackson had been writing novels and stories for nearly two decades before embarking on her tale of Hill House, a mansion where visitors can turn up any time they like but find it rather hard to leave.

Netflix’s Salt Fat Acid Heat ushers in new age of cooking show

Her earlier works were striking, wrote Jackson’s biographer Ruth Franklin a couple of years ago, not only because they were such accomplished contributions to the strain of American gothic that includes Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe and Henry James, but because they foregrounded women. Her stories feature single women desperate for the social acceptance of marriage, or married women trapped in domestic situations so stifling they were (often malevolent) characters in their own right. Jackson herself was increasingly desperate in her marriage and in the imposed role of homemaker.

The Haunting of Hill House was her first book to earn its advance, and more: Franklin notes that Jackson used the surplus to pay off her mortgage. Its film rights were sold and turned into a movie by directorRobert Wise, who had just finished making West Side Story and would go on to make The Sound of Music.

The book was a finalist for a National Book Award along with novels by Saul Bellow, John Updike and Philip Roth (who won with Goodbye, Columbus) – writers who became household names synonymous with seriousness, while Jackson’s body of work was dismissed as middlebrow thrills, skilfully produced by a housewife who, unhelpfully to herself, sometimes claimed to be an amateur witch.

How most famous Chinese horror story collection was written by a clerk

Shortly after The Haunting of Hill House was published, Jackson became so ill with agoraphobia and colitis that she barely made it to the premiere of the film in 1963. “I have written myself into the house,” she said to a friend, and it was true in many more ways than one.

Hill House, “not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for 80 years and might stand for 80 more”. Dr Montague, a doctor of philosophy, wishes to investigate what constitutes the darkness, which has led to the house being shunned by all who live nearby. He intends to live there for a summer, with as many people as he can find who have a sympathy for the paranormal.

Two women – Eleanor, who as a child once seemed to activate a poltergeist, and Theodora, whose empathy is such that she can effectively read minds – answer the letters he sends out. Along with a young man called Luke, who is to inherit Hill House, they form a cosy party of four (not counting a housekeeper who resembles an automaton, and her grouch of a husband, who cares for the grounds). Stephen King once called the novel “as nearly perfect a haunted-house tale as I have ever read”, but it is much more than that.

The book is thrillingly well written, full of complex, economical, vivid insight. Dr Montague’s letters are described as having a certain “ambiguous dignity”; a couple of boys Eleanor passes on her way to the house stare, “elaborately silent”; a marble cupid on a Hill House mantel “beamed fatuously” down at the two women, whose talk is punctuated by “the comfortable small movements of Luke and the doctor taking each other’s measure” in a game of chess. Even seemingly throwaway descriptions carry weight and set off echoes, and the dialogue dances with wit and subtext, making sudden shifts in tone from sunshine to the chill of cloud passing over.

So the doctor, telling the tale of the house – built, its angles deliberately off-kilter, by a man called Hugh Crain, whose young wife died in an accident as she entered the grounds, and whose daughters then fell out over it – notes: “It was said that the older sister was crossed in love … although that is said of almost any lady who prefers, for whatever reason, to live alone”.

For this, in the end, is the crux and power of the novel – the ways in which judgments and expectations dictate, trap and make vulnerable the outer and inner lives of women. Eleanor’s existence so far has been “built up devotedly around [the] small guilts and small reproaches, [the] constant weariness, and unending despair” of caring for a seriously ill mother; her trip to Hill House is the first thing she has done entirely for herself and she is giddy with freedom and the sense of new beginnings.

The house behaves as haunted houses will, but the tension increasingly comes from wondering whether Eleanor’s hope of independence, of chosen friendship and love, will be fulfilled. Does she have a chance at happiness? Moments of pure fear are followed by a sense of excitement, a kind of hectic community and camaraderie.

These twists and turns are far harder to pull off on screen than shrieks and groans and things that go bump in the night. The creators of Netflix’s 10-part retelling of the novel have decided to go back in time and tell the story of what it was like for the original Crain family to live in what they are calling “the most haunted house in America”.

They have decided, also, to expand the family, including Theodora and Eleanor as two of five siblings, with the narrative flipping back and forth between the children and their modern-day grown selves. Since the psychic ramifications of family are at the heart of the book’s considerable power, it suggests a haunting can be just as much about trauma, about memory and the unquiet unconscious as about the paranormal.