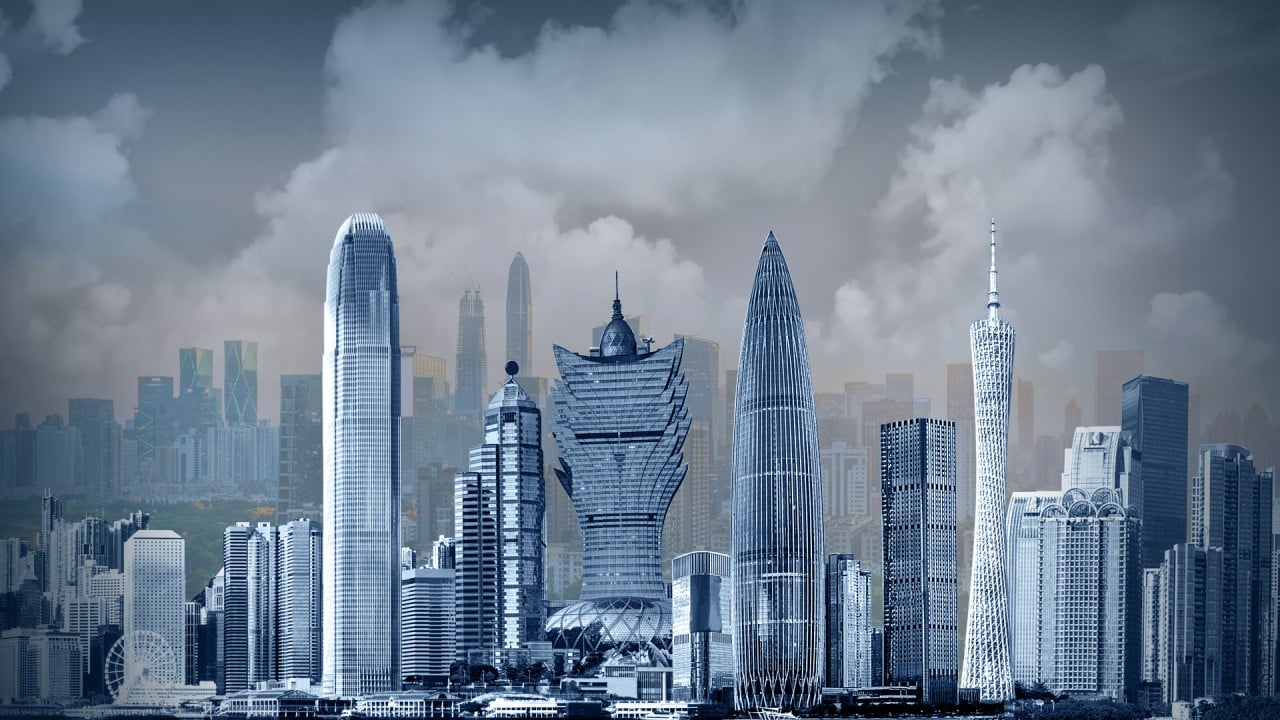

Hong Kong’s denial of dependent visas to mainland spouses sends wrong signal on Greater Bay Area integration

- The exclusion of mainland spouses of Hong Kong permanent residents from the standard dependent visa system means they must rely on the arcane and problematic one-way permit

- This seems very out of place, given Hong Kong’s ambitions to be a modern city. However, the solution is simple: expand dependent visa eligibility

As a project of regional economic integration, its success will ultimately be determined by the free exchange of goods, services, capital and people. Here, I want to focus on people.

Hong Kong student visas and other less-common visas can also come with dependent visas. The logic seems clear – if we want people to settle here, it is crucial that they can bring their families with them. Practically every immigration system in the world recognises this.

This detail is contained in the Immigration Department’s visa guide section describing people for whom the dependent visa “does not apply”, which also includes “nationals of Afghanistan and Korea (Democratic People’s Republic of)”.

This strange exception runs counter to both common sense and international practice. For family reunion rights, no one ought to have a higher priority than the immediate family of citizens or permanent residents.

But in Hong Kong, when permanent residents (whether Chinese or foreign, it does not matter) marry people from the mainland (many of whom are from the Greater Bay Area), their spouses do not qualify for a dependent visa and must instead use the arcane and highly problematic one-way permit scheme.

The permit scheme, which comes with a quota, has been around since the 1980s and has facilitated many family reunions. In short, mainland spouses can apply to their local authorities to relinquish their household registration and leave for Hong Kong permanently.

Turning away mainland migrants won’t benefit Hong Kong

For example, during the seven-year waiting period, the person does not have citizen rights in either mainland China or Hong Kong, since they have no household registration permit and no permanent residence. Thus, they cannot get a passport, but instead must use the yellow-green “document of identity for visa purposes” that is also issued by Hong Kong to refugees and stateless people.

This situation might have been less problematic in the past, when the world was simpler and mobility was limited. But, nowadays, many people are unwilling to use the one-way permit for any number of personal or professional reasons, and thus would have very little chance of a family reunion.

A common practice is to use a visitor “super visa”. An ordinary visitor visa for mainland Chinese lasts only seven days but a “super visa” can be good for 90 days at a time. This allows for longer family visits without de facto statelessness. But even this is cumbersome, and does not come with the right to work or to acquire Hong Kong permanent residency.

The one-way permit system, and in particular the exclusion of mainland spouses from the standard dependent visa system, seems very out of place given Hong Kong’s ambitions to be a modern city. It certainly sends the wrong signal to the Greater Bay Area – that an important group of people are either not welcome or will not be treated on equal terms when they try to come here.

The solution is very simple, which is to expand dependent visa eligibility to all mainland Chinese. The one-way permit system can stay if it is not too much trouble – the quota is never fully used anyway, and it has a different set of requirements from the dependent visa, so some people might still opt for it.

Without equal access to the standard dependent visa system, the cross-border families being discriminated against under the current policy will continue to face hardship, and more people may choose to make their homes away from Hong Kong.

On the other hand, opening up equal access would not be difficult, either legislatively or administratively, and it would certainly send a very positive signal that Hong Kong is serious about integration with the Greater Bay Area.

Patrick Jiang is an honorary research associate at the Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies of the Chinese University of Hong Kong